The Death of the Cubicle and the Profit Motive

by Wholesome Rage | 28 June 2019

Robert Propst invented the office cubicle to improve the quality of life of office workers in the mid-60s. The padded, insulated walls and customizable work environment was meant to be a big improvement over the heavy tables lined up in tight rows like a school classroom.

What was meant to be private spaces workers could move around in became twisted towards packing as many workers into as tight spaces as possible. The cubicle farm was born.

The cubicle farm began to be synonymous with the misery of office work. So, around the early 2000s tech boom, they were done away with, increasingly in favour of open-plan designs.

Were workers given more space, more distance from each other? Not really. Recent walkouts from the Vox offices drew this tweet:

Let’s dismiss the argument as absurd. Josh Sawyer’s reply mirrored my own reaction:

But let’s also look behind that for a moment at the Vox office itself: It’s a cubicle farm, but without the cubicles. The space is crammed, two people share a desk facing each other, with a person at each shoulder when the office is at capacity.

This open plan design is more familiar to my generation. It’s the post-cubicle office environment, and while the greater emphasis on windows and natural lighting is appreciated, the loss of the acousting-blocking walls, and even less space than the cubicle factory-farm, isn’t. That is, when they get their own space at all.

Visually, it’s a less oppressive work environment. Functionally, it sucks. It’s the aesthetic of liberation of the worker, while in practical terms making life worse. Because the appearance of doing something is emphasized over the more costly practical solutions.

According to the New York Times:

The move to take people out of private offices, the better to improve collaboration and productivity, has little empirical justification. Most widely cited studies of employee satisfaction tend to run against such trends in office design. A study from The Journal of Environmental Psychology in 2013 indicated that 50 percent of workers in open-plan spaces suffer from a lack of sound privacy, and 30 percent complain about a lack of visual privacy.

So why do it? If it’s active sabotage of stated goals, then it would mean that the appearance of improvement has become the most important objective.

That’s not all though. Workers are also often more motivated to look busy, appear to be working, than to actually work. While in theory hired to ‘do a job’, workers who overperform are directly punished for this with more work, or being fired..

As a result, it’s less important to be _busy than to _appear _busy, in workplaces that are designed to _look less oppressive rather than to be less oppressive. Form is mistaken for function.

I think it’s because the form has more easily measurable qualities.

For instance, happiness and enthusiasm has become a popular metric for worker productivity. Many companies follow a principle of routinely firing the lowest 10% of workers on some metric, and now happiness can be one of them. That New York Times article above even has this paragraph:

Tony Hsieh, the C.E.O. of Zappos, has argued that companies ought to employ ‘‘chief happiness officers’’ to ensure enthusiasm at the office. He has also suggested that they regularly identify the 10 percent of workers who share the least enthusiasm for the ‘‘happiness agenda’’ — and fire them.

Firing your ‘unhappiest’ 10% might mean firing the most stressed-out employee who’s taking the greatest share of the work. If you’re routinely in a bad mood because, say, your parents died a month ago, that can result in termination.

But, again, we find that the _appearance _of a productive quality - happiness - is emphasized because it can be measured. Employees often find themselves working harder to appear productive than they do… producing.

This isn’t a new idea. Philosopher Eeva Berglund put it like this: ‘The information that audit creates does have consequences even though it is so shorn of local detail, so abstract, as to be misleading or meaningless - except, that is, by the aesthetic criteria of audit itself.

If you don’t fully understand what that means on the first read, here’s a comic about Wittgenstein explaining the implications. Mike Judge demonstrated it fantastically in the movie Office Space, showing the game we’re made to play by our reaction to someone refusing to play it._

But Berglund’s quote specifically is useful in understanding why so many nonsensical things end up happening in larger systems. We all know that education is worsened when we teach-for-the-test. But the test is how we measure the quality of education. The best measurements, then, come from the worst practice. We also see that better practice is outright punished when test scores are then tied to funding.

Fundamentally, this means that everything in our working lives comes down to optimizing for the values we’re assessed by, regardless of how practical or good those values are.

Mark Fisher writes in Capitalist Realism:

The idealized market was supposed to deliver ‘friction free’ exchanges, in which the desires of consumers would be met directly, without the need for intervention or mediation by regulatory agencies. Yet the drive to assess the performance of workers and to measure forms of labor which, by their nature, are resistant to quantification, has inevitably required additional layers of management and bureaucracy. What we have is not a direct comparison of workers’ performance or output, but a comparison between the audited representation of that performance and output. Inevitably, a shortcircuiting occurs, and work becomes geared towards the generation and massaging of representations rather than to the official goals of the work itself. Indeed, an anthropological study of local government in Britain argues that ‘More effort goes into ensuring that a local authority’s services are represented correctly than goes into actually improving those services’.

This, to me, seems to be the most compelling explanation for the slow death of the cubicle.

This is also a good primer for understanding why the profit motive is so devastating. You’ll hear a lot of critics of capitalism say things like “capitalism is incompatible with environmentalism”, and it can be difficult to understand what those statements mean. Capitalism is people, and we need the environment to live. Surely it’s at least in the interests of its own self-preservation?

But if the only measurement that firms care about is profit, and it cares about profit only in ways it can measure and quantify, then a lot of decisions that might seem inexplicable make a lot more sense.

It’s the same problem that leads to teaching for the test. Or to open plan offices that function worse than cubicle offices, but appear less oppressive.

It has been said that the first simple AI we invented was the corporation, and that it is a paperclip maximizer for profit.That the corporation neither loves you nor hates you, but that you are composed of material that might be converted to profit.

We can see this most clearly in the games industry.

Five days ago, Nintendo announced that they were pushing back the release date of Animal Crossing to ensure their employees had a healthy work-life balance. As a result of the announcement, Nintendo’s stock dropped by a billion dollars in that same day.

Other companies, because of this, are unlikely to stop implementing crunch practices of forcing workers into unhealthy, long hours. Reports are of 100 hour work-weeks for periods of months.

The long term effects of having healthy, well-treated employees are opaque. A billion dollar loss in equity, however, is far more easily quantifiable.

This is in spite of the fact that not only is there no proof that crunch results in more output, but there is a lot of evidence that it doesn’t work. That evidence, however, comes with a caveat. To quote the linked article: Productivity is hard to quantify for knowledge workers.

Man-hours is much easier to measure, so the quantity of man-hours will often take priority over quality from those worked hours. We know that from how Team Bondi treated its employees. This is old news I saw in print, so I’m afraid I’ll have to say it was in an Australian magazine called PcPowerPlay around 2011, and see if I have a copy of it in storage somewhere to confirm it, but one thing it noted was that Team Bondi had a record of hiring the cheapest, new coders it could, and packing its staff with them while employing sweatshop practices.

An experienced coder, the article said, would write about ten times as much code per day, but cost three times as much. However, by measuring the production time in man-hours and not lines-of-code per day, Team Bondi “optimized” for what it was measuring..

From the failures of Team Bondi we can learn two things: That companies will pursue horrific tactics in pursuit of profit, and that these mistakes are being made with millions, sometimes hundreds of millions, of dollars thrown at these problems.

One implication of that is that having millions, or hundreds of millions, of dollars to throw at these problems is not enough to solve them. Even massively successful companies, like Valve, are not immune to issues of optimizing towards bad values.

Recently Valve has been in the news because of the aggressive tactics that Epic Games has been using against Valve’s Steam platform. One thing that was noted in Jim Sterling’s ongoing reporting of the conflict is that it might finally encourage Valve to fall back on its own advantage of successful IP.

Which begs the question: Why has Valve not been developing its brand-name games already? The last Half Life game was in 2007. Left for Dead 2 was 2009, and Portal 2 came out in 2011.

That was their last single-player game to date, June of 2019, and that doesn’t appear to be changing anytime soon.

The Week reports on this in its evocatively titled How capitalism killed one of the best video game studios, and it’s unique in that the company is still alive and thriving. It generates a terrific profit - it draws $4.3 billion dollars in revenue from the up-to-30% cut it takes from game sales on Steam.

A Resetera forum post quotes former Valve employees:

Valve have discovered that cosmetic microtransactions are big money makers, and thus every team at Valve was dedicated to that vision. When I was there (before Artifact started in open development) there were essentially no new games being developed at all. There was a small group that were working on Left for Dead 3 (cancelled shortly after I joined), and a couple guys poking around with pre-production experiments for Half-Life 3 (it will never be released). But effectively all the attention was focused on cosmetic items and “the economy” of the three big games (DOTA, CS:GO, and TF2). One very senior employee even said that Valve would never make another single player game, because they weren’t worth the effort. “Portal 2,” he explained, had only made $200 million in profit and that kind of chump change just wasn’t worth it, when you could make 100s of millions a year selling digital hats and paintjobs for guns (most of which are designed by players, not the employees!)

And-

In theory, employees are allowed to (supposed to, even) work on whatever they think is valuable. In reality, you should be working on whatever the people around you think is valuable or you’re gonna get fired really quickly. (Fewer than half of new employees make it to the end of their first year.) This usually means doing whatever the most senior people on the team think is important, both because they should know if they’ve been there for a while, but also because they wield enormous power behind the scenes.

We see the optimization problem clearly here. Because making art is not the most profitable use of time, it is discouraged - even in what should ostensibly be a groundbreaking games design company, even when employees are told they have the freedom to pursue their own ends.

We see this in much the same way the worker ostensibly is there to do a job, but is really encouraged only to work as much as it takes to not be hassled, not be fired.

Mark Fisher again explains this phenomenon best in Capitalist Realism:

The reason that focus groups and capitalist feedback systems fail, even when they generate commodities that are immensely popular, is that people do not know what they want. This is not only because people’s desire is already present but concealed from them (although this is often the case). Rather, the most powerful forms of desire are precisely cravings for the strange, the unexpected, the weird. These can only be supplied by artists and media professionals who are prepared to give people something different from that which already satisfies them; by those, that is to say, prepared to take a certain kind of risk.

Finally, we come to the most insidious case that shows the contempt for humanity behind the death of the cubicle. So far everything described has been a function of trying to extract more productivity out of workers, or at least what it can measure as productivity. Team Bondi is an unusually optimistic cautionary tale about hyperexploitation ultimately being less profitable, though that’s not always true.

What happens when these values run into the unemployed?

First, let’s explain the concept of ‘natural unemployment’. In a capitalist economy there is always going to be structural unemployment - the skills of jobseekers do not match the requirements of vacancies - and frictional unemployment - the time it takes to fill a vacancy in a market with available positions.

The natural unemployment rate is the combined rate of these two things, and is fairly unavoidable. Long term unemployment for some is not only inevitable, but baked into the system.

Unemployment is treated as a measure of how good or bad a government’s economic policy is. What this means is that policy that reduces unemployment is valued not because it’s good in and of itself, but because it looks good.

Here’s the trick to the above: To count as ‘unemployed’, you have to be actively looking for work. That means there are two methods of lowering the unemployment rate: Getting those people jobs, or bullying them out of the labour force.

Guess which approach we’ve been seeing in the last few years.

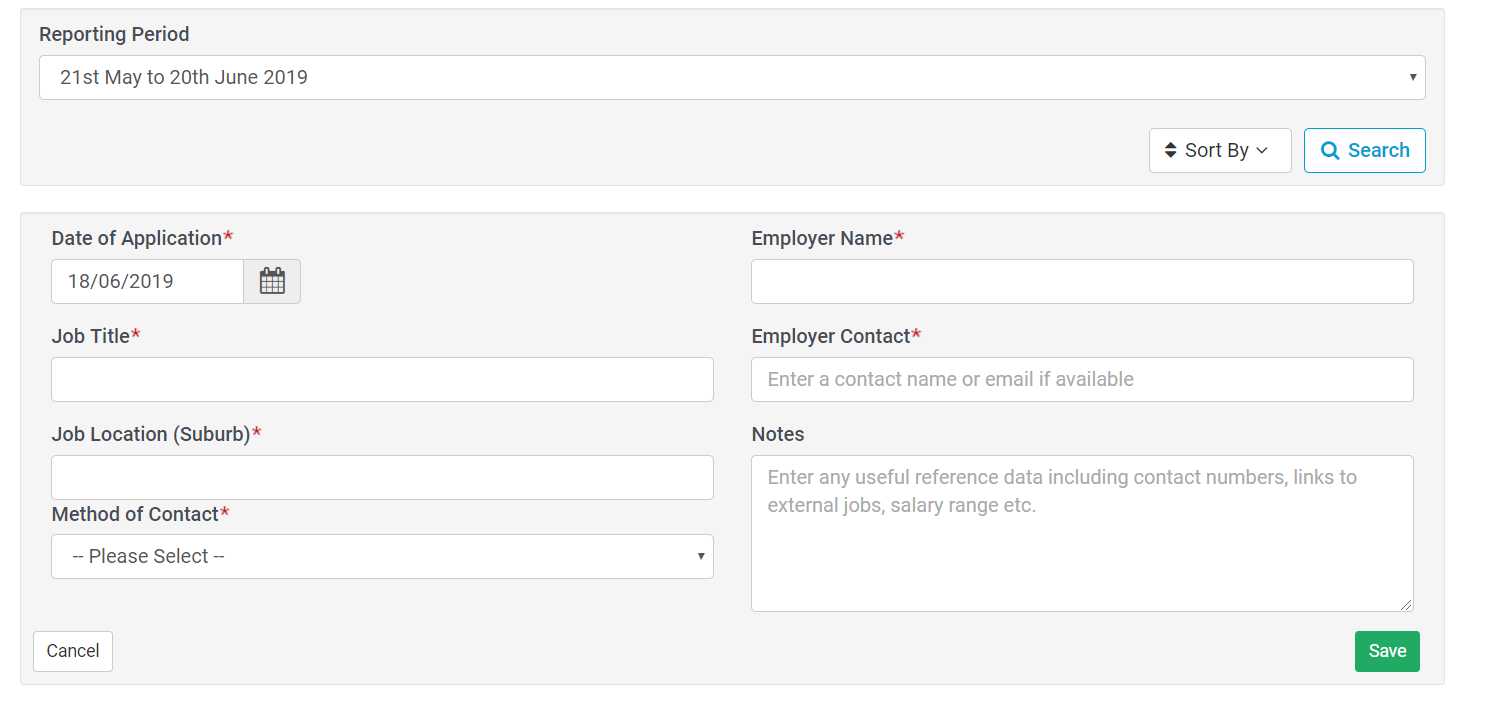

Consider Centrelink, Australia’s system for providing unemployment payments. Currently, to receive benefits below the poverty line, Australians have to submit and report 20 resumes. Reporting through the government tracking website looks like this:

Failure to do so will result in the cutting of your benefits, which can take months to acknowledge. My unemployment claim with disability benefits took four months to process.

In that time I managed to find enough editing work on commission to meet the hours required. I was then told that this work doesn’t count towards employment, or the hours I need to work, but I must still log the income.

This is because commission work doesn’t particularly fill a form neatly. The priority is not the stated goal - to assist in employment - but appearing to meet that goal. On that ground, working irregular hours fails.

As well, the granular reporting of the resume submissions creates so much paperwork that nobody can really check it all. Because this is known, and the loss of benefits is held over people’s heads, more work ends up being done on the reporting of resumes than sending them to the right places.

All of this is checked up weekly, or monthly, by a job agency that you’re assigned, in theory to assist you. In practice, the only job I’ve been offered through this system was a janitorial position at an industrial bakery that wasn’t accessible by public transport.

Non-attendance to these appointments will result in the loss of benefits, as they are quick to remind you.

Again, we find that the existence of the audit is significant because it has consequences, and not that the information it generates is meaningful,

This is somewhat intentional. This allows there to be two statistics which seem totally at odds with each other. One set of statistics shows that this system is actively harmful to the unemployed, reporting that “people were overwhelmingly dissatisfied (73%) with jobactive service, with 8% satisfied.”

The other statistic generated is that it lowers unemployment. Not because it results in the unemployed getting jobs, but because they have dropped out of the labour force. They are no longer counted.

For the unemployed who get benefits, there must be audits to show that they are the worthy unemployed. To provide work which shows the problem is being solved.

In reality, that’s what it is. Work to show that the right things are being done. The reality is irrelevant - form serves as function.

Much like the tearing down of cubicle walls, conditions have worsened to give the appearance of improvement. The reality of how much these decisions worsen people’s lives is irrelevant. In the context of this decision making, the unemployed are worthless but for the value that can be extracted for them.

Ultimately, it’s difficult to offer a solution for this. We don’t live in a world where we have the luxury of asking that most people aren’t valued by what, and how much, they produce. So long as that remains true, we’ll find systems created to ‘optimize’ people towards those ends, while also trying to disguise that intent.

The death of the cubicle, then, is that it was a victim of its own success. It became too recognizable for showing the values of the system. If the values of the system couldn’t change, then it would have to be our ability to recognize them.