The Art of Murder

by Wholesome Rage | 15 August 2019

A few articles ago, I came up with a prompt for an all-fighter murder mystery tabletop campaign. Someone liked it so much that they’ve commissioned me to actually write one..

It’s been great fun! But it’s also made me have to think hard about how I’d go about making one. The hardest part, conceptually, was asking what a good murder-mystery to play even was. What I thought would be a simple question made me realize a lot of my examples gave lessons that were mutually exclusive. It turns out murder-mysteries have a surprising depth of variety to them—depth of variety meaning that not only are there a lot of different takes on what it means to play a murder-mystery, but that the differences themselves are huge.

On the one hand, this shouldn’t be too surprising. The existence of the ‘roguelike’ is only as old as the 1980s, but its mutations range from procedurally generated card-game bossfighters like Slay the Spire, to tragic-baby shooter Binding of Isaac, to the recently released Void Bastards.

The murder-mystery long predates video games and goes back to the late 19th century, with the publication of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, as well as the works of Edgar Allen Poe. Murder-mystery genre conventions have had a hundred years longer than roguelikes to mutate and mature. That also means they’ve been popular for far longer, and had an additional hundred-years-worth of contributions.

When you’re trying to make your own contribution, this is just as much a drawback as it is a benefit.;there’s more to study, more examples of what does and doesn’t work, absolutely. But there’s also more audience literacy, more cliches, more ideas already taken. More ideas that have simply been done to death.

There’s a very general flow that all murder-mysteries seem to follow - solving puzzles helps you understand the story, and understanding the story helps you solve future puzzles.

This is different to the adventure genre, where the puzzles are the story. Games like Myst and The Witness ask you to find out why the puzzles exist by solving them, and games like Paradigm or Monkey Island make an interesting world when the puzzles you’re confronting involve, say, murdering a water cooler.

The murder mystery instead requires you to make educated guesses about the story, and uses puzzles to check to see if you’ve come to the right answer. Where the more you know, the more you can figure out.

This requires a well-written story that makes the players want to guess what happened, as well as allowing for complex clues. Solving one part of the case shouldn’t unravel the whole thing too early. The Ace Attorney series, in particular, is often guilty of this, where you figure out what happened too early and the game devolves into a tedious exercise in trying to figure out what specific piece of evidence the game wants for each statement.

It also requires puzzles that challenge players without frustrating them. This is why I personally dislike most adventure games—I think of them as having ‘Banana-Knife-Rope’ puzzles, named for the Trapped trilogy by Godlimations, where one puzzle required you to fish in the sewers by using a knife superglued to a rope as a line, and the banana as bait.

A good murder-mystery game, then, is all about creating ludonarrative. It’s often the story of a brilliant detective solving the crime, and solving the puzzles should make you feel like a brilliant detective. This means that the puzzles should feel logical to the story, and the story feels paced by the puzzles.

Which brings up a tricky question, then: how do you make a murder-mystery puzzle in an environment where basically everything is done to death? When the locked-room mystery has been done so often that nobody even remembers a time when it was meant to give the appearance that the murderer ‘vanished into thin air’.

The meta-knowledge that we possess as a result of seeing the same puzzles recycled over and over means that the player doesn’t feel clever for solving them. Instead, you feel like the puzzles are make-work for your character to figure out what you already know. You start yelling at the ‘brilliant detective’ in your head the same way you yell at horror movie characters “Don’t go in there!”. This is what we call ‘ludonarrative dissonance’.

Again, this is the biggest problem I have with Ace Attorney games—especially since that series has gone on long enough that it’s developed a recognizable formula.

The issue is the ‘mystery’ component. Player literacy in roguelikes probably means they’re going to pick up and learn a new iteration faster, be better at it. For roguelikes, this is good.

For a mystery game, though… well. It rather defeats the point, doesn’t it? As one example, “the Butler did it” is such a cliche, and has been subverted so many times, that now people cannot be surprised in either direction.

There’s a much more useful cliche, though: “You don’t understand something until you can explain it”. I’ve just written enough of this mystery campaign, and am pleased enough with it, that I thought it’d be worth explaining what my inspirations are, and how they tackle this problem of creating mysteries in a saturated environment.

Unlike roguelikes, mysteries were born as a literary genre. This means that it’s not enough to ask how the games are played, but how the gameplay is used to tell a story. Or how important telling a story is to making a good murder-mystery game.

The mystery game also breaks away from other mediums in the sense that the author has complete control. Games require a little bit of it is given to a player, which puts a lot more stress on the design. The fact that it’s a game can’t be a secondary consideration, but the primary one.

The three main things to consider for the murder-mystery game genre would be;

- Narrative-as-puzzle - how to make the gameplay assist in the storytelling, how to tell a story that couldn’t be told as a book or a film.

- Death-as-narrative - how to make death in your plot feel impactful and significant. Why solve murders and not heists?

- Puzzle-as-narrative - how to create ludonarrative; how to make the player feel like a big-brained detective solving the mystery.

I’ve chosen one game for each of these considerations that I feel demonstrate them the best. Spoiler warning for the games in advance, though I’ll try to keep them to an absolute minimum.

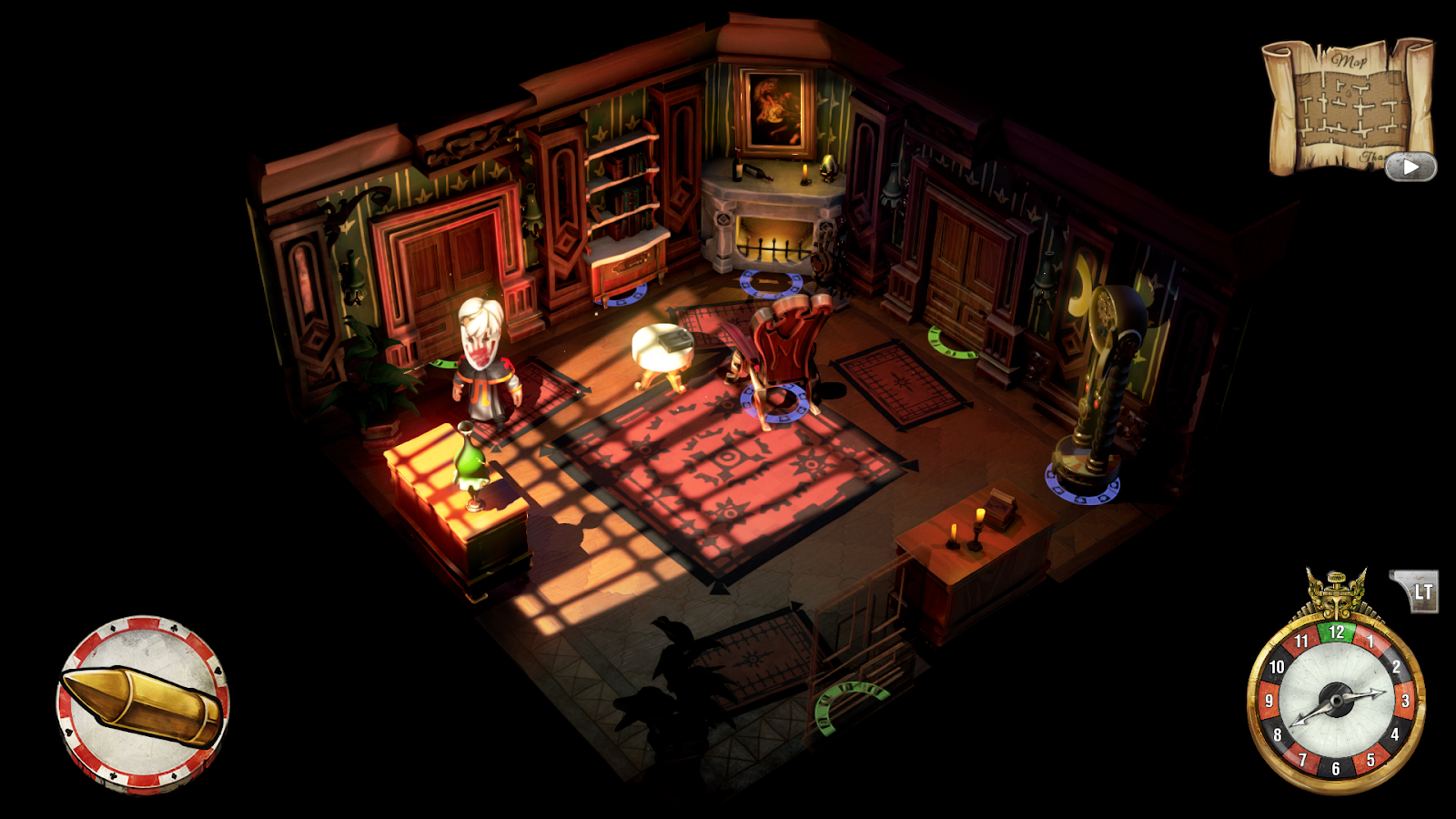

The Sexy Brutale

Narrative-as-puzzle

From http://www.thesexybrutalegame.com/

The Sexy Brutale starts with a common theme to the best murder mysteries, and the one factor in common to all four games I talk about here - Start with a unique ruleset.

In the case of the Sexy Brutale, it’s Groundhog Day. The player is a guest in the Marquis’s annual masquerade ball, but this year something’s gone horribly wrong: all the guests are being murdered by the staff. The protagonist is then granted a special power that allows him to rewind the clock.

This power is contained within his masquerade mask, which he must never take off. He can’t be in the same room as someone else wearing their mask, or else their mask will chase him out of the room. (It makes sense when you play it, I promise.)

Every midnight, time rewinds, and the protagonist starts back at the last clock he’s set his pocket watch to. Another chance to try and save the guests.

Because of this, the Sexy Brutale offers murder-mystery in another iteration—nstead of solving murders, it’s about figuring out how to prevent them. You know exactly how the murder is done, as well as who’s responsible. The focus isn’t on assembling a case or catching the killer. Instead, the game is about learning how to prevent the deaths and save the guests, without being allowed to talk to them or even be in the same room as them.

However, when the clock resets, _everything _resets. You can’t save them all, you barely have enough time to save even one of them each cycle. So, as the game progresses, the sound cues you hear throughout the game take on new and macabre meaning as you realize what they signify, which guests you failed to save.

Before I keep talking about it, I want to say that The Sexy Brutale was easily my game of the year in 2017. The entire thing can be beaten in a single playthrough and its message had a strong impact on me.

The Sexy Brutale is an amazing story that could only be experienced as a game, not as a movie or a book. The ludonarrative is what made is storytelling so effective.

So this comes back to the gameplay element of murder-mysteries. The puzzles exist to pace the narrative, and to align the player with the protagonist. To make them feel like they’re solving things.

The problem with traditional murder-mysteries is that figuring out the clues leads to better clues and more context of the crime. It’s jarring when the player jumps ahead of the clues, though, and waits for the game to catch up to them.

The Sexy Brutale is elegant in how it solves this. The second you have enough information to solve the puzzles, you can solve them. The rewards are a new gameplay mechanic to be able to solve the other murders, which you do in a linear fashion.

This means that the puzzles can afford to be rather simple. They’re more narratively interesting than they are mechanically complex, giving you an at-your-own pace chance to learn about the characters in order to save them—another advantage of the time-loop is that there isn’t a sense of urgency, except for that gnawing in your gut caused by the tragic deaths.

What The Sexy Brutale offers to the genre, then, is proof that complex puzzle-solving isn’t needed if the story itself is very strong, and that is more important to focus on designing the puzzles in a way that serves the story.

In solving the deaths, you learn a lot about the characters you’re trying to save, and the larger mystery behind everything. The puzzles themselves are fun, absolutely, but it is the fact that you’re solving them that is more important than that they’re being solved

You see the whole murder. Quite a lot, actually. But the ‘how’ rarely answers the ‘why’, which are two very different questions.

I wish I could say I was taking more inspiration from the Sexy Brutale in my own work, but its mechanics are too unique and tied to its ending—the real mystery—that not much translates.

I can, however, take from it a piece of design philosophy: a great murder-mystery does not need to rely on complex puzzles, or challenging mysteries. It can instead be thought of as a game that is uniquely positioned to deal with grief and loss and mistrust as its themes.

Many detective-centric games don’t actually address this. Sherlock Holmes was a scientist playing a game against the criminal, after all. Police procedurals are about bringing people to justice.

But The Sexy Brutale—and Danganronpa, which I’ll talk about next—instead tells a story about actually feeling hurt by these deaths, personally affected by them.

In this, it doesn’t make sense to feel like a big brained detective, or scientist, or scholar. It’s important to make the player feel what their protagonist is.

In the Sexy Brutale, you play as Lafcadio Boone. An old priest.

In the game I’m designing, the players will be playing as the local police for a small community where everyone knows each other. More important to me than making complex puzzles should be making gameplay that reinforces that loss of community, of being untrained police officers making hard choices.

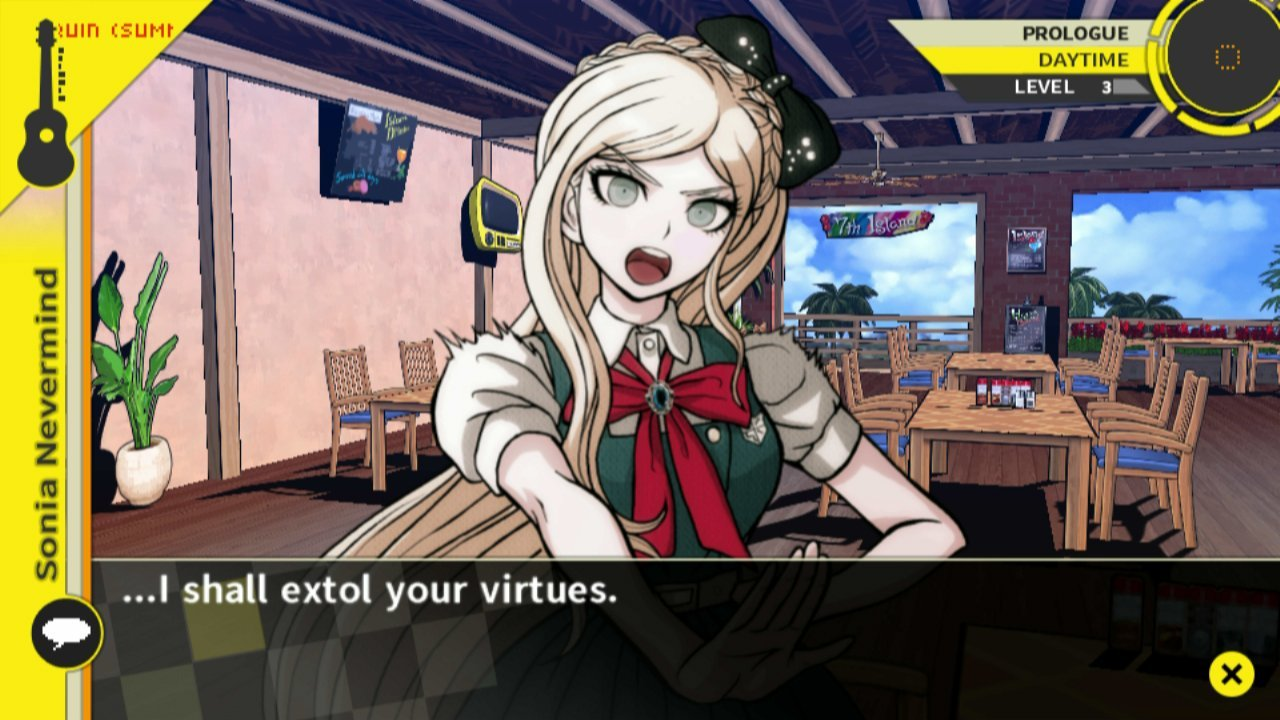

Danganronpa

Death as Narrative

First hot take: the reason Ace Attorney isn’t on this list of inspirations is because I believe the Danganronpa series does everything Ace Attorney does, but better.

Danganronpa 1, 2 and V3 are such well made games that they last with you for days. They demand friends to talk about it with, and they can hit you so hard it hurts.

I have good reason to suspect, though, that Danganronpa didn’t come from uniquely talented writers. Second hot take: none of the games had a good ending. I couldn’t stand them, if I’m being honest.

Another good reason to suspect it is that, according to Aragon, Conception is one of the worst anime he’s ever watched, and he makes a habit of binge-watching the very worst anime he can find.

This naturally begs the question - how do the people responsible for some truly terrible twist endings, as well as an absolutely horrific anime, still manage to produce one of the most iconic contributions to the murder-mystery genre?

Personally, I think it’s because they figured out the strongest formula for murder-mysteries I’ve ever seen.

Here are the rules of Danganronpa: you start off with a ‘class’ of fifteen characters. They are trapped in a location which is fairly spacious, and has all their material needs met, but they cannot leave or communicate with the outside world.

To leave, you have to murder someone and not get caught. After every murder there’s a brief investigation period, and then a class trial. Everybody votes on who they think the murderer was.

If they choose correctly, the murderer gets executed, and they return to their imprisonment. If they choose wrong, everyone but the murderer is executed, and the murderer gets to go free into the outside world.

Or, if the murderer is caught every time, the last two surviving people are free to leave. That’s a very large ‘if’, however.

Here’s why this premise is so strong: those fifteen people you start with? That’s everyone.

Every murderer is someone you knew. Every victim is someone you knew.

Every case means that, at a minimum, two people are removed from the game: the victim, and the executed murderer. That’s a minimum, though, as some cases can have multiple victims.

After four or five cases, suddenly the game is down to only you and maybe three other people. Three other people who you’ve put your life in the hands of several times now, who’ve gotten you through everything—and also Yasuhiro is there too.

Danganronpa is an exceptional murder-mystery in its trial mechanic, which is what I mean when I say that it does Phoenix Wright better than Phoenix Wright. Just trial-for-trial, I believe Danganronpa has better cases and fewer frustration moments… so long as you set the awful minigames to their easiest difficulty, which you always should.

But what Danganronpa does well that I most want to emulate, is that emphasis on the significance of murder-as-narrative. Most murder mysteries have characters arrive after the crime has already happened and try to work out the motive.

Danganronpa is a little different. You know everyone. You were spending your free time with them, so some characters have perfect alibis. Often you have to prove who did it beyond reasonable doubt, and they’ll only tell you the ‘why’ as their final confession before their execution.

Because… they’re your friends. And you can’t believe any of your friends would have done something like this. But it’s three cases in, and you know better now.

Danganronpa is uniquely good in that it shows the grieving process: it shows the characters having to deal with their friends dying around them. It shows the significance of death not merely as a puzzle to solve, but as a source of character progression from a storytelling perspective.

When the trial starts, you’ll start repeating things in your head like; “Please, anyone but them”, and sorting the survivors in your head as ‘must live’ and ‘acceptable losses’. It’s a cold calculation, but you play favourites when you know someone has to die. You’ll have to rely on people for evidence and their expertise, even though you know they could be the killer. The investigators are all suspects.

And, in later cases, you think of how useful a character would be right now if they were still alive. Even just as moral support. But they were murdered over something stupid instead.

The most brilliant—and unintuitive—element of Danganronpa is that the game it’s built on top of is essentially a dating simulator: during your free time events, you can hang out and flirt with the surviving classmates, give them gifts, find out more about them. Get closer to them.

This means it really twists the knife when they die. Or when you have to out them as the murderer.

My own game steals two elements from Danganronpa. The first is the structure of interacting with the relevant characters before a murder, and then having the murder happen after a major event that the players were directly involved in. The events before a murder always help to explain it in some way, and the clues are often given to you before the murder starts, if you know how to look for them.

This is a great way to dispense clues, because it means both that players act as first-hand witnesses to events—the only testimony they can truly trust—and because it means that clues aren’t clearly contextualized as clues until later. The players don’t know what crime they’re solving yet, so they don’t have the corner pieces of the jigsaw to work inwards from.

The other element is ensuring that every victim and every suspect was useful and valuable to the players before their deaths and/or accusations—To make fun and interesting characters that you’ll miss seeing around. I think that emotional weight is what puts Danganronpa in a league of its own.

So why did I put Sexy Brutale first, if it’s clear that Danganronpa is a bigger inspiration?

Because, while Danganronpa creates brilliant, hard-to-solve puzzles to work with, I’m writing my own game for tabletop; I don’t actually have the bumper rails of a coded video game to work with. Tabletop GMs rarely have the opportunity to say ‘you can’t do this’ that a videogame can. Its limitations allow this aspect of the design to be more effective.

Sexy Brutale was important to put first in order to emphasize that it’s okay to take from Danganronpa the feelings I want, and not have to worry about matching the complexity of its puzzles. I don’t think I can replicate something so complex in tabletop without it being a nightmare to run, and too convoluted to play.

Without counterexamples, it can feel defeatist. Like setting yourself up from the start to being an inferior product. When often times, what’s good design in one framework is terrible in another.

The Sexy Brutale gave me permission to best think how to use puzzles to convey feeling, without feeling obligated to match Danganronpa’s complexity. To remind me to think to emphasize the ludonarrative I want, and to understand why I’m choosing the pieces that I am.

Sometimes, it’s about understanding what not to take.

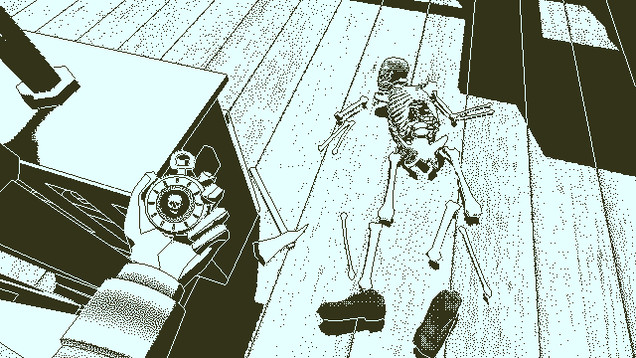

Obra Dinn

Puzzle as Narrative

I’m glad Return of the Obra Dinn came out in 2018, because it means I don’t have to choose between it and The Sexy Brutale for my game-of-the-year picks.

If The Sexy Brutale is narrative-as-puzzles, where the puzzles exist to pace the story and immerse the player in the narrative themes, then Obra Dinn is its inverse: solving the puzzle is the story.

Obra Dinn, unlike my other examples, actually is a story about being a big-brained detective. Well, not a detective per-se, but rather the insurance investigator for a ship: you’re determining the required payout after the ship is discovered and everyone on board is found dead or gone missing.

Again, we come back to the fact that these games all seem to work so well because they have a unique rule system. Obra Dinn’s is a magic pocket-watch, the memento mori. When you find a dead body, the memento plays the last few seconds of sound, and then shows you a freeze-frame diorama of the instant of death. Fortunately, you can also find dead bodies in these memories, and then jump through them.

Is the mystery to solve what happened to the ship? Not really. The game makes that as obvious as possible.

No, instead you’re given the ship’s manifest, some artist’s drawings of the crew, and told to find out what happened to each and every individual crew member. Correctly link every memory to a cause of death, and the person who died.

The artist’s drawing doesn’t give names. The names don’t have pictures. The screen is black when the pre-death audio plays, so you can’t tell who’s saying what.

The game confirms your guesses only when you get three correct choices at the same time, and there are about sixty people to lock in. Many deaths happen offscreen, and some characters don’t die at all.

The story of the Obra Dinn, then, isn’t about what happened to its crew. It’s about how you solved it.

The Obra Dinn is what I took inspiration from in designing my puzzles, and not Danganronpa. This is because Danganronpa, with its narrow focus, can afford to give you the guardrails. Everything you can click on is relevant in some way, and you can only click on relevant things during an investigation.

The complexity of the mystery can match the fact that the information you get is curated and very high signal-to-noise.

The Obra Dinn doesn’t give you that. The Obra Dinn wants to make you feel like Sherlock Holmes.

The only method the game has to check your answers is if you entered the right name and cause-of-death to the right face at the right time. It doesn’t care how you get those answers.

This means that guess-and-check is a valid method, albeit very slow and tedious with so many combinations to choose from. Instead, you might notice that one man’s tattoos remind you a lot of Pacific Islander designs. You check the manifest and, yes, there is one name from Papau New Guinea.

The Obra Dinn doesn’t give you pipe ash in the corner, and a character who’ll narrate to you - “Ah, yes, this is from a Whitney cigar,” and then put the ash in your inventory to tell you it’s significant. The Obra Dinn makes you feel brilliant when you notice, instead, that you notice a man smoking a pipe that you saw left on a table in a numbered cabin, and you can check the cabin number against the manifest to get a name…

There are many ways to figure out the right answers, but it’s still a challenge to figure out any of them.

In the context of the Obra Dinn, this is ludonarrative as narrative. The insurance investigator is only as smart as your ability to play them, and they feel brilliant when you’re brilliant. The story of what happened to the ship is far less important than the story of how you figured it out.

This form of puzzle design seems like it would work best in a tabletop iteration. Do all the work up front on knowing all the specifics of a crime, all the people you could talk to, and make multiple ways to get to the same conclusion.

The trick isn’t to make the mysteries themselves especially clever, but to realize players will never know about the clues they didn’t find. Making a scattering of small clues that complement each other does more for making the player feel like an investigator than any ‘trail of breadcrumbs’ approach taken by traditional mystery games.

My resulting philosophy for designing this game—which I’ll be very excited to playtest to see how it works in practice—is that my only goal is to place a needle, and I trust the players to bring their own haystacks.

There is a fourth and final note I want to make on what I believe makes a bad mystery game, though, that should be important to remember when thinking of the ratio of needle to haystack.

Unheard

Sometimes, it’s about understanding what not to do. Sometimes it’s just as important to break down why you didn’t enjoy something, to be able to understand what makes other examples work so well.

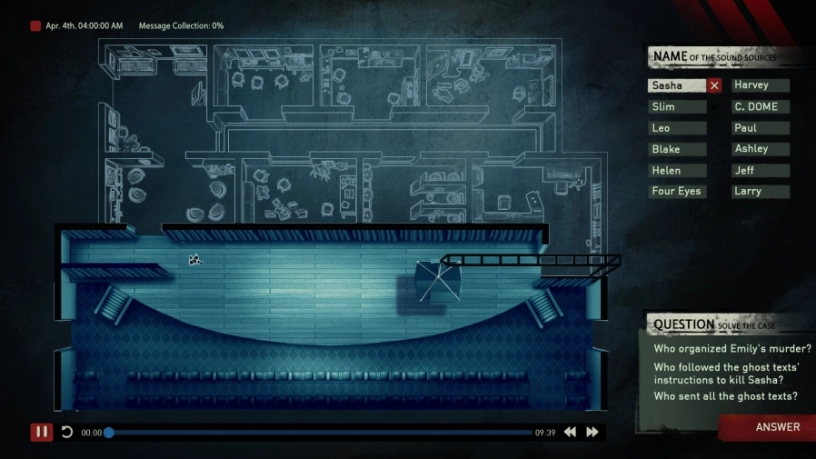

Unheard is an interesting mystery puzzle game where you have to solve a crime. You can only hear everything that happens before the crime occurs, and where it happens on a floorplan.

This sounded like a very cool idea, until I played it and realized that essentially this was problem solving by stenography. Most of the challenge of solving the puzzles came from listening to multiple clips of the same 8 minutes of audio over and over again, as all the clues were given explicitly in dialogue.

If you just listened to the puzzle long enough, in enough places, and you wrote down what happened when, it was trivially easy to solve.

Unheard seems like it would pair well with the lesson learned from the Sexy Brutale again, but the Sexy Brutale’s puzzles were short. Often knowing the gist of an answer was enough to solve the whole thing, which isn’t true for Unheard.

As well, the information that you learned during any individual puzzle went towards your understanding of the larger story. Unheard was frustrating because the extra details I sat through felt like they’d be quickly irrelevant, forgotten at the end of the mission.

So, simple puzzles that are more about learning a story work when the story feels larger than what’s covered by the puzzle. Sexy Brutale felt great while Unheard felt tedious because Sexy Brutale built towards something, whereas Unheard didn’t.

I can also note that I loved how the Danganronpa games managed that feeling of progression, even though I ultimately didn’t like the endings that it was building towards. Ideally, I’d like to have a satisfying ending, but it means I know to build smaller arcs in a larger story rather than several totally episodic stories like the original seasons of the X-Files.

It also threw up a warning flag for trying to make puzzles using Obra Dinn’s design philosophy. If there are no logical leaps, if the puzzle feels like it could just be solved with a notepad and pen, there’s never that ‘a-ha! I’m a genius!’ moment. Running into too many clues that lead to the same conclusion can feel condescending, as well.

This means making enough clues to lead to certain ideas, but also making spaces between ideas that require a logical leap, or a deduction. Pieces of the information that there is no evidence for, but make the most sense.

How to manage giving enough information that the puzzle is solvable, but not enough to feel condescending or like stenography busy-work, is going to be the needle to thread. Which I imagine is easier said than done.

Conclusion

Exercises like this are important when making art. Taking ideas from any one thing is plagiarism, but take it from a dozen and it’s research.

I have a very bad habit of having a huge stick in my rear when watching things, or playing games. But part of it is that I’m always pulling apart the media I consume and breaking it into its component pieces.

This doesn’t have to be a miserable experience, and it doesn’t ruin your ability to enjoy things. Aragon enjoys all sorts of objectively terrible manga because pulling it apart is so much fun for him.

It just means asking: what works how and why? What am I seeing in this that I saw elsewhere, and did it work better there?

Most of the time, you can’t answer those questions on your own.

I think the most important part of breaking things down is having friends who enjoy breaking them down with you. The car conversation you have coming out of the cinema is probably how you best understand what you just watched, and what you liked about it. How you best understand where the pieces fit together.

The hard part is finding people who disliked Danganronpa’s endings as much as I did.

The reason I remember these games specifically is because they’re the ones I enjoyed talking to people about the most. I played Sexy Brutale twice through screenshare with friends, and the Obra Dinn was something I talked about for weeks with friends. Danganronpa is a favourite conversation topic in the chat I share with Ben Pearce and Aragon.

Making art is a lonely, often thankless task. But art exists as a conversation, and understanding your own feelings of it requires conversation. None of these insights are thoughts I could have had if I hadn’t had to compare my own feelings to someone else’s.

And you don’t really understand anything until you have to explain it.