Aragon on; Attack on Titan

by Aragon | 18 September 2021

Attack on Titan, or Shingeki no Kyojin if we’re being Like That, and we’re not, is a manga written and illustrated by Hajime Isayama, which ran from September 2009 to April 2021, and it’s bad. It’s really, really bad.

But it’s bad in a fascinating way.

Narratively speaking, Attack on Titan makes some incredibly stupid mistakes. But that’s the thing, right? It also does some things incredibly well. Only, those things it does incredibly well actually make the story worse as a whole. It’s incredible. It’s super entertaining. Don’t read it. It blows.

So that’s what we’re talking about today. This review will be split in sections for ease of reading, and it will contain full spoilers of everything Attack on Titan. You don’t need to know anything about the series to understand this review, and I don’t recommend you read it if you haven’t already.

This is going to be a long one.

Editor’s note; The original draft of this piece had the text below the image. This has been updated to be mouseover text where relevant.

The Story

[Note: Please, keep in mind that the screenshots are read right-to-left]

Attack on Titan can be roughly split into four parts—as in, what the story is actually about changes three times as the comic goes on. The genre, the hook, the reason why you’re reading it—it keeps evolving, it keeps mutating; there’s no real status quo for this series.

This is why some readers dropped the series very early into its run, while others got incredibly hooked. Some people couldn’t stay engaged after all these paradigm shifts, while others revel in them.

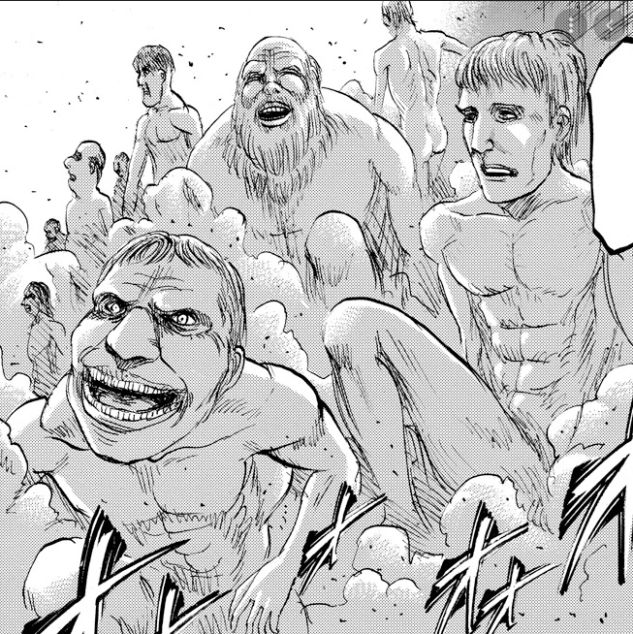

So at the start, Attack on Titan is an ontological mystery: most of humanity has been wiped out by the titular titans: massive human-like monsters, ugly as all hell, who kill and eat any human on sight. Meeting a titan is an immediate death sentence; they’re strong, fast, never tire, and brush off most wounds.

We don’t know what they are, or where they came from, or why they’re there. They just showed up one day and started killing people, and it’s been more than three hundred years and they never stopped.

The few humans who survived live in a single country, surrounded by giant walls. It’s a militaristic, steampunk society. They have guns, but they don’t have electricity, that sorta deal. Nobody knows how their ancestors built those walls. All they know is, the titans want them dead.

So that’s the setting. The hook is, our main character’s mother is eaten alive by one of these titans, so he wants to take revenge. He wants to kill all titans, and while we’re at it, discover what titans are and where they came from.

This is what the story is about for the first few chapters; then, the first of those three big paradigm shifts happens: the main character himself—Eren Jaeger—turns into a titan during a fight. Turns out, he can do that! Humans can do that.

Translations insist on using hepburn romanization, which means that you translate shit phonetically rather than properly. Like, one character is French, and clearly supposed to be named Rivaille, but they translated it as “Levi” because Kodansha is like, genuinely, bottom of my heart, fuck the readers.

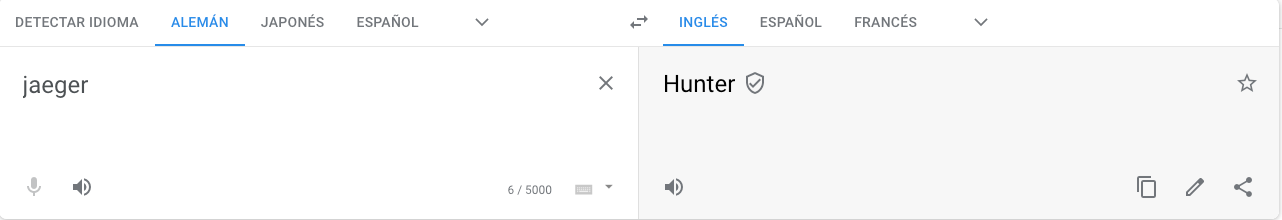

This also means the official translation uses “Eren Yaeger”, even though his name is very obviously meant to be “Jaeger”, “Jäger”, German for “hunter”. He wants to kill all titans, the whole narrative is about the hunted becoming the hunters, etcetera etcetera. Jaeger.

This is the least radical shift the story will go through—I mean, the titans look like messed-up humans anyway, so it’s not that crazy a jump in logic to think “oh, maybe they’re actually humans.” It’s not unexpected.

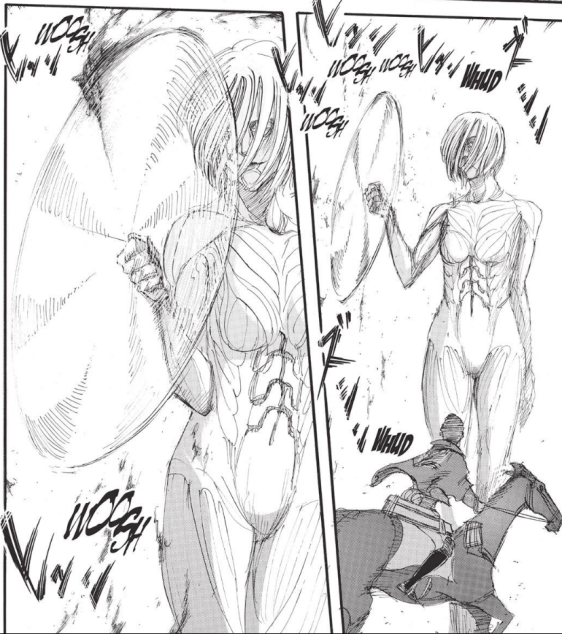

However, it changes the vibe of the story a lot. Up until now, meeting a titan equals certain death; the comic establishes this relentlessly, it has entire chapters dedicated to the idea. Just seeing a titan is a traumatic experience that changes you forever; surviving that encounter makes you a war hero.

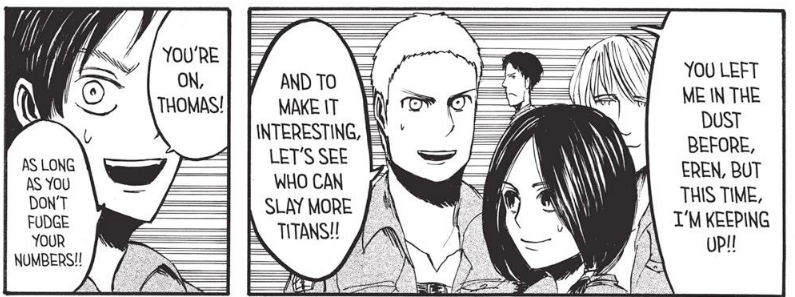

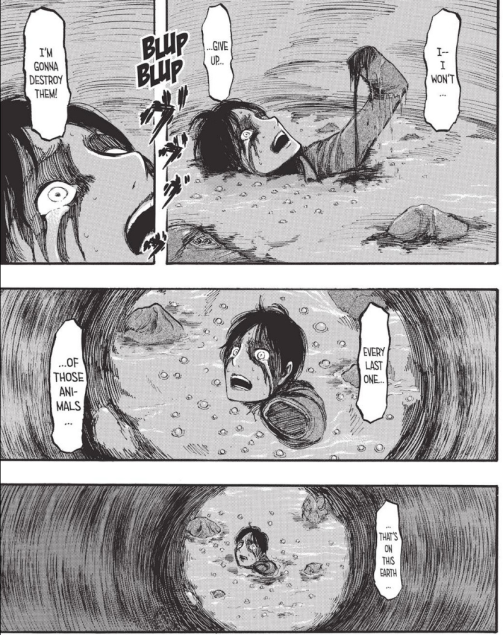

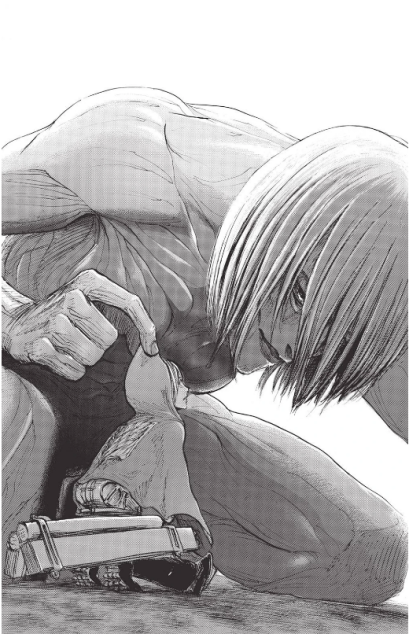

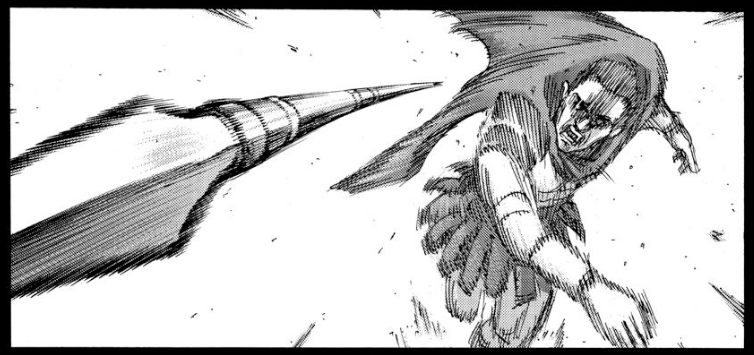

The last picture here is one of the main characters, as soon as they meet their first titan. It’s a very Games-of-Thrones-ish moment, establishing that:

A) Anyone can die.

B) Main characters are not exempt from this fate.

Only now, Eren can turn into a titan and just Jackie Chan his way out of a fight, so like, sure. Why not. There goes the hopeless vibe of the story.

The first time I tried to read it, this is where I dropped the series, because soon enough other people start having titan powers, and Attack on Titan becomes the Power Rangers but with big naked people instead of giant robots, and like, I’m good, thanks.

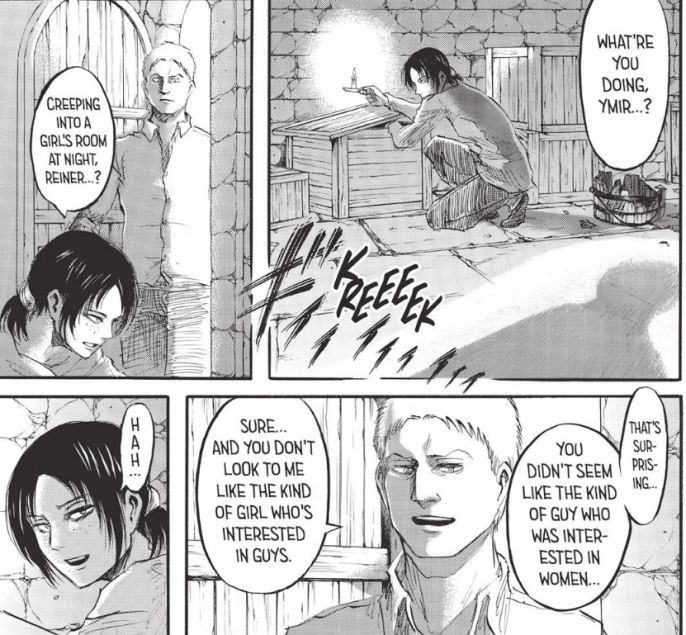

So, after this, as I said, it turns out other characters can also turn into titans. These ones are evil, though, so that’s what the story’s about for a bit—find out which of the main characters is a traitor titan-shifter, and learn why they’re doing this, and what is going on, and where do titans come from, etcetera.

There’s also a subplot at this point that’s like, oh, hey, are these people gay? These people are super gay-coded. Are these people hooking up? And the answer is, hahah, nah, we’re gonna bury the fuck out of our gays, so that’s a Whole Thing. More on this on the “Characters” and “How Attack on Titan’s attitude towards women is despicable” sections later.

And then, the second shift happens.

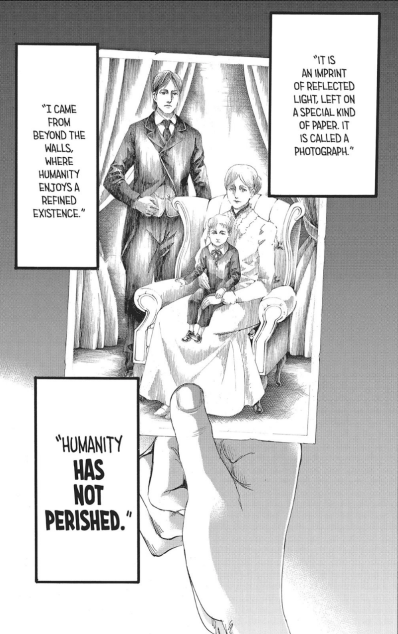

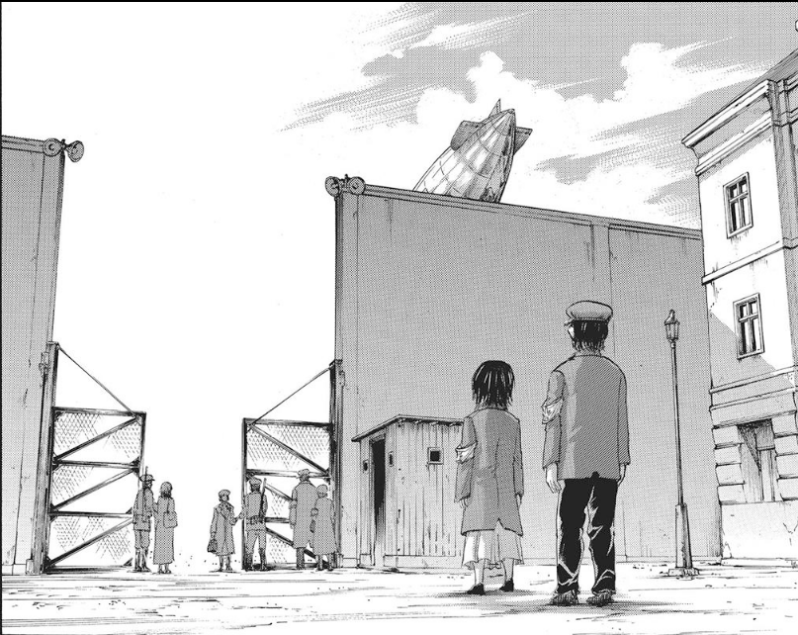

This is the biggest twist in the story. Just like the first one, it’s telegraphed well enough that it’s kind of predictable—there’s life outside the walls, and that’s where the titans come from. That said, the twist keeps going: while the island where our characters live is a soft steampunk sorta world, the rest of the world is on an early-1900s level of technology, with electricity and planes and trains and so on. Every titan, indeed, was a human once, but the world is not full of titans either—it’s just this one island.

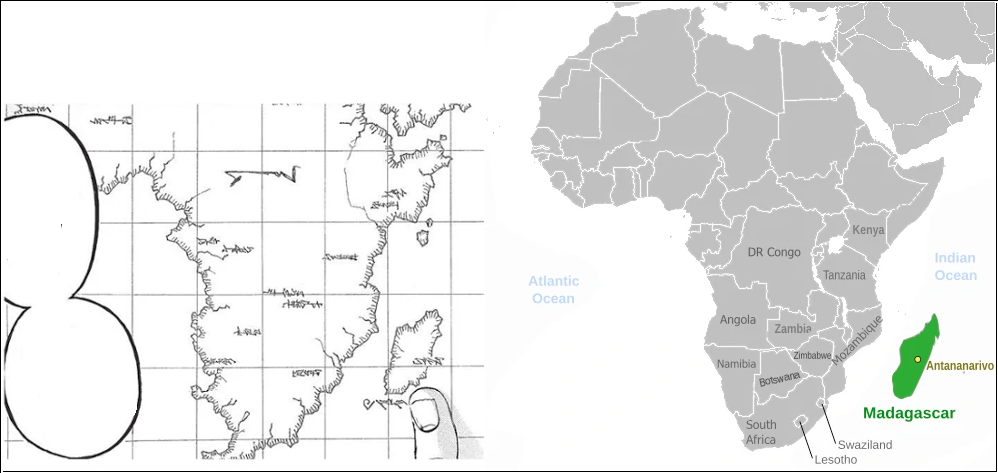

Also, the series has been set in Madagascar the whole time.

Also!

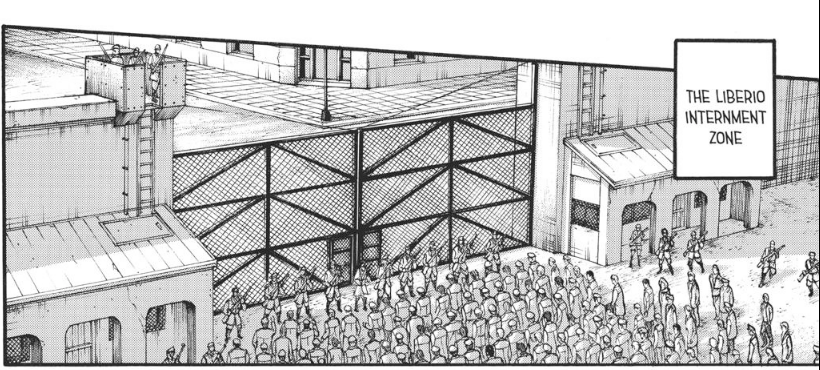

The series has been set in a concentration camp the whole time!

Turns out, the rest of the world hates the people of this island, which, we discover, is named Paradis. I groaned, too, but if you want subtlety you really can’t be reading manga, it won’t be good for your health.

The people of Paradis are the only ones who can turn into titans, mostly against their will. The island of Paradis is a prison, the titans are thrown there to keep them in check, and Attack on Titan is now a story about racism, but most of all, it’s a story about genocide.

2. Attack on Titan is a story about genocide

And not in a good way. Not in a “let’s explore the consequences of a genocide, which is a human tragedy so great in scope it’s hard to even understand it emotionally”, but rather, in a “genocide is unavoidable and arguably not that bad” way.

Hell of a thesis.

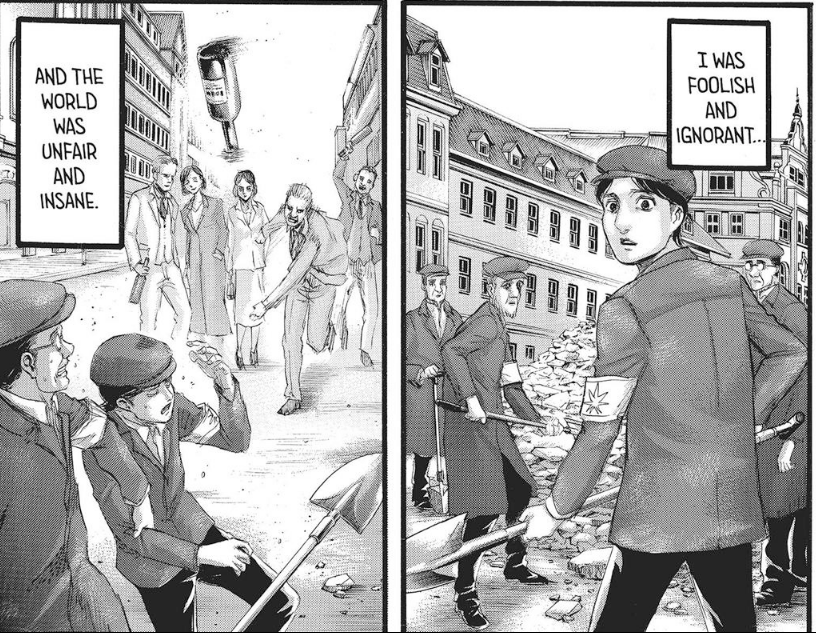

Anyway. So after this second paradigm shift, there’s a timeskip, and the story gets sidetracked for a while. We see what happens in the outside world, and learn that the people who come from Paradis are discriminated against in a very horrible, inhuman way.

We see that the traitors who could become titans were sent by this outside world to prevent the people of Paradis from learning the truth. We see that our main characters have infiltrated this outside world and are investigating it, incognito.

We see our main character, Eren, kill a lot of innocents. Emphasis on how he kills civilians, women, and children.

We don’t know why. The other characters also don’t know why. Eren has changed after the timeskip and is now way more edgy, and also more quiet and somber. Hence the killing of civilians and children. He’s brought back to Paradis, and he, uh.

He kind of, how do I explain this.

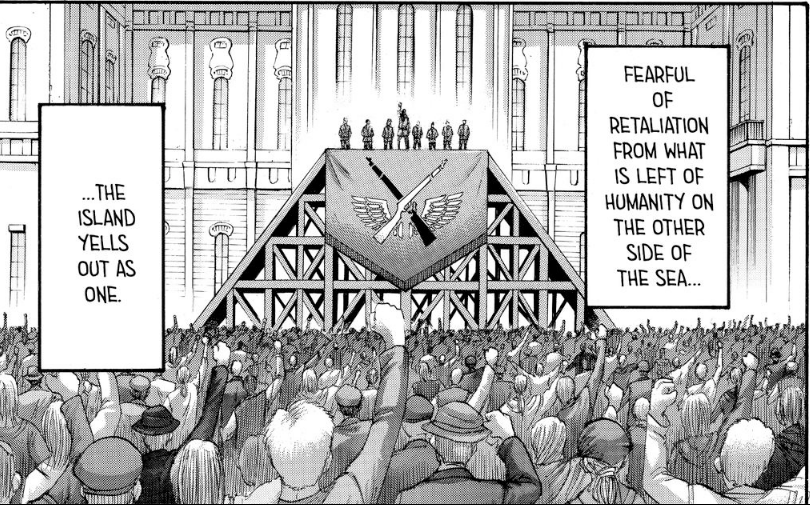

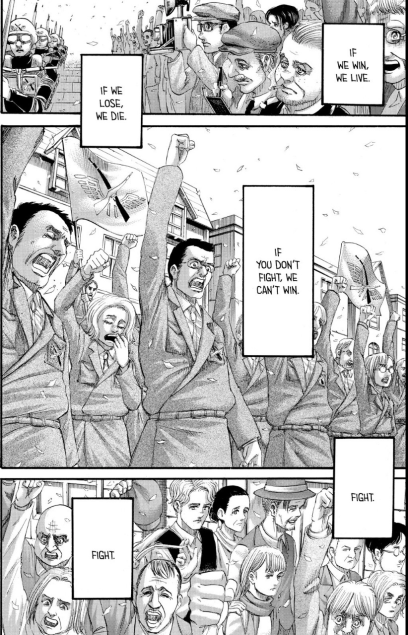

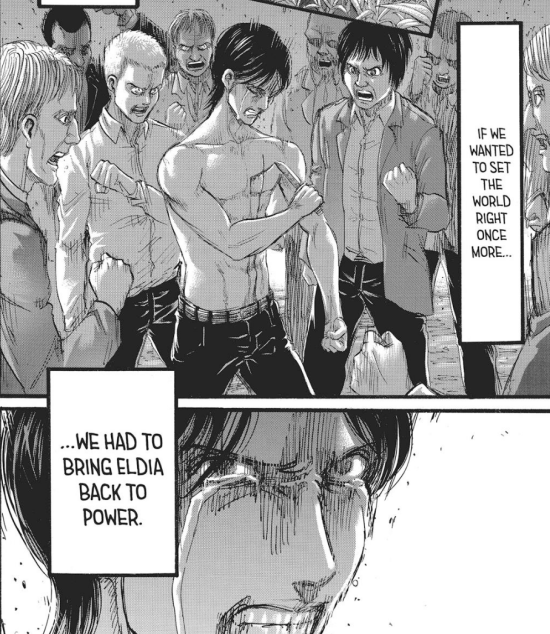

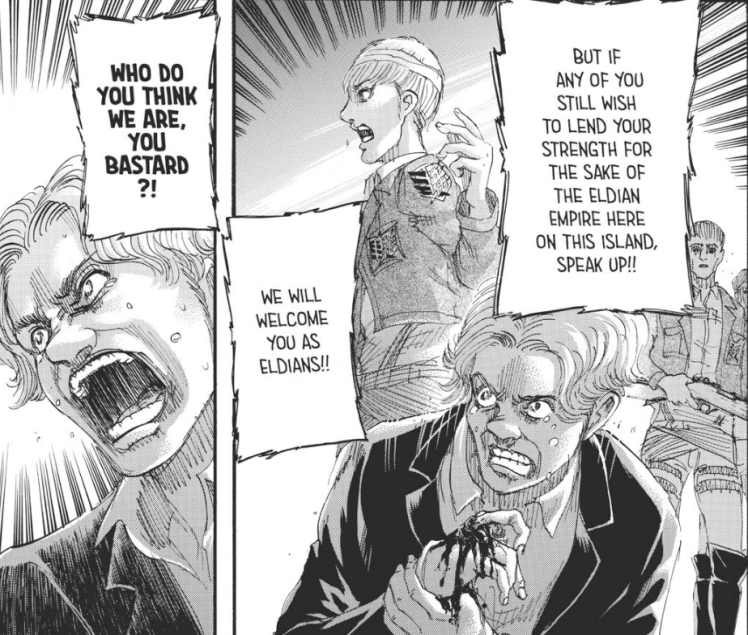

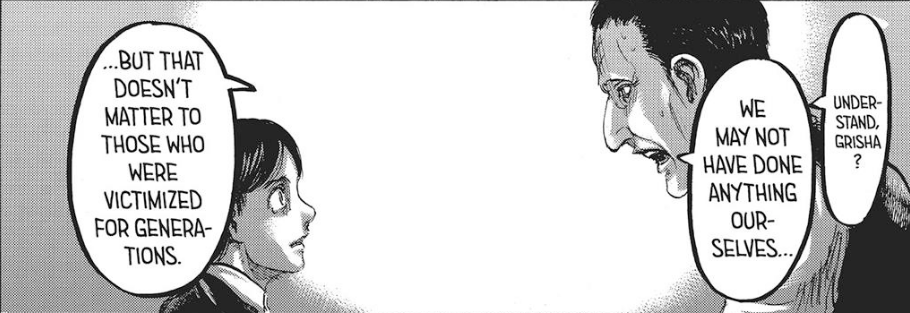

He creates something called the Jaegerists, a party of extremist, militaristic warmongers, who want to kill anyone who’s not a member of their race. The way they put it, the people outside of Paradis hate us, say we’re inferior, but actually they’re inferior, and they’re making us pay for the sins of our past, and we will not let that happen, and HEIL-

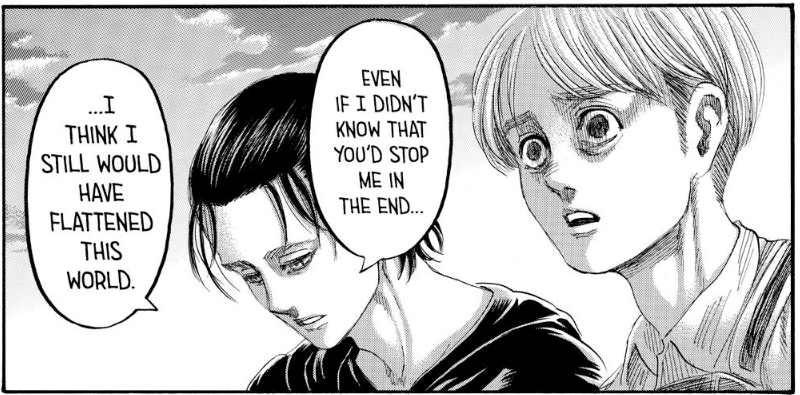

Yeah, you know what, more on this later. Third paradigm shift happens now, and it’s summarized in three points:

A) Eren Jaeger, our main character, can see the future. He’s been able to see the future for years, now.

B) Eren Jaeger is now a villain protagonist.

C) Eren Jaeger commits genocide.

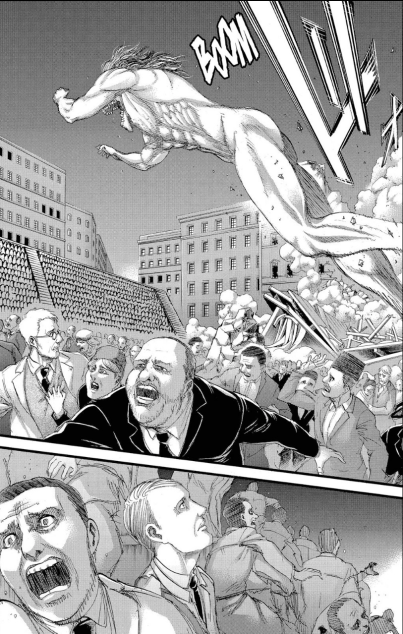

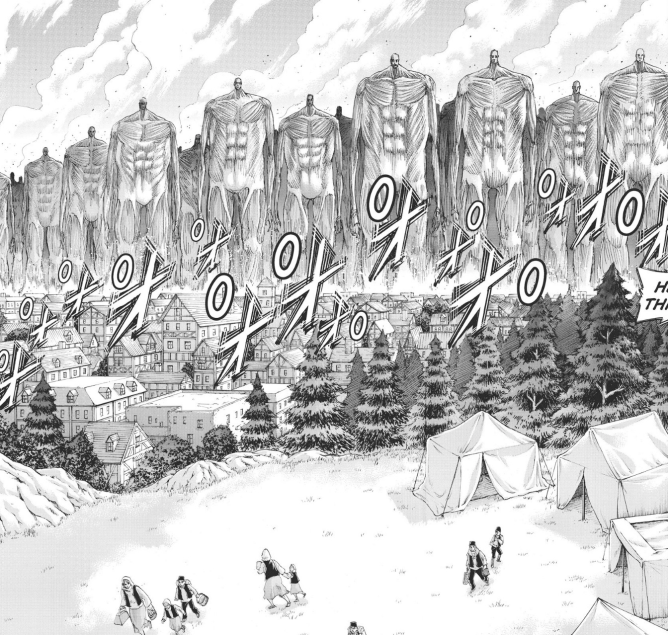

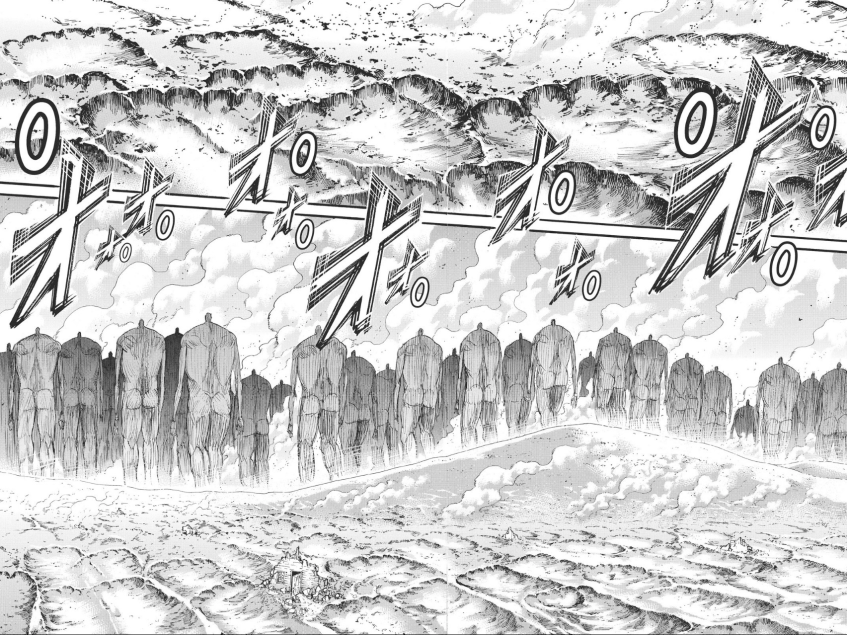

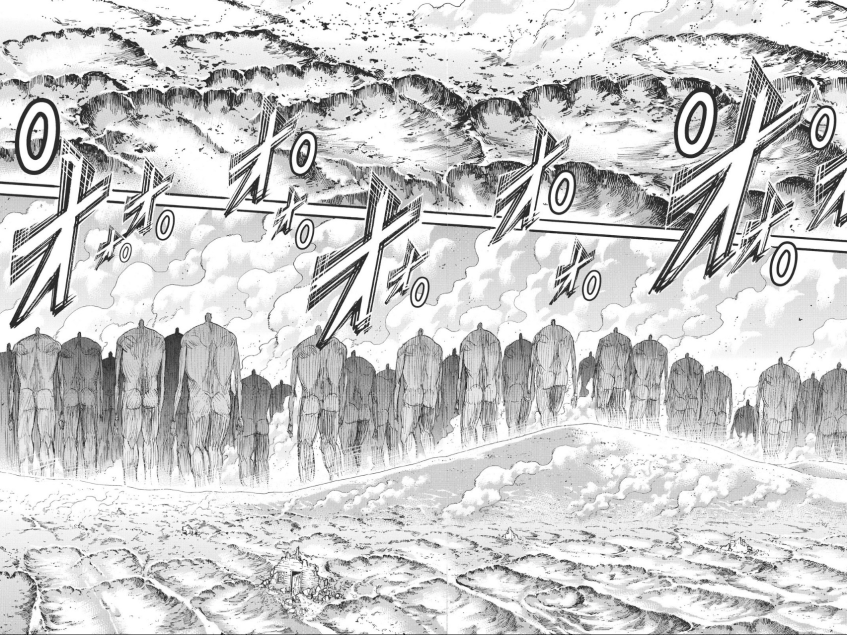

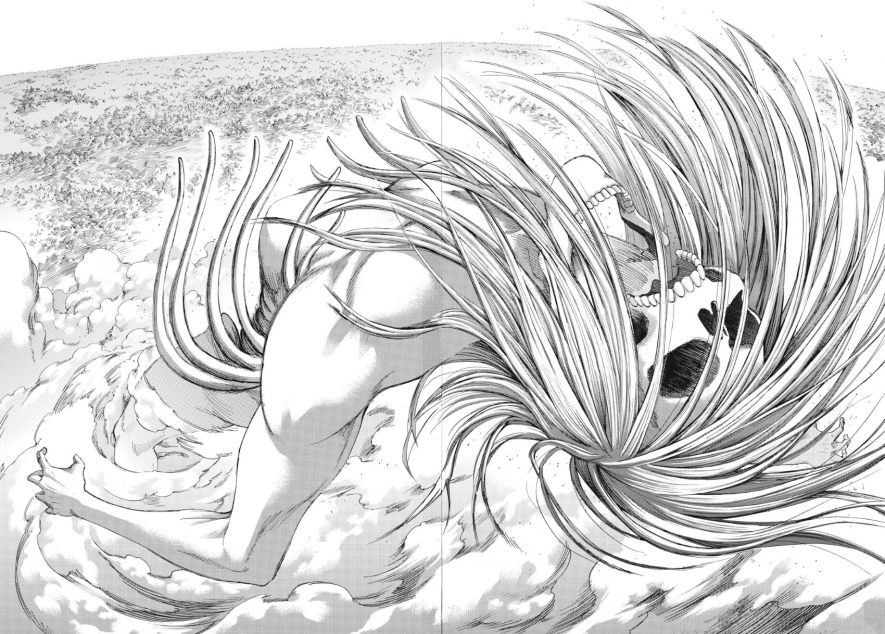

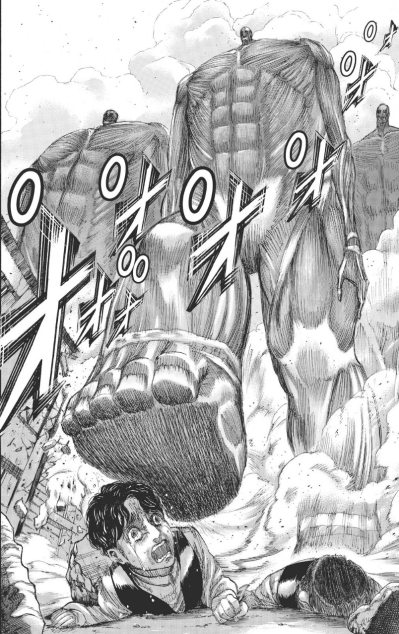

Remember the walls that I mentioned all the way back? The ones that protect people against titans? They’re made out of very big titans, actually. Millions of them. Eren, for a series of convoluted reasons, can control them. So he does that, and he uses his new army of colossal friends to commit genocide.

The story is now about the rest of our main cast trying to stop Eren from committing genocide. They chase him around the world, and find him, and eventually stop him, and the story ends with the death of our main character.

And also most of humanity.

The text of the story, the things the characters say, indicates that this is a bad thing. The subtext of the story?

Yeah, nah. “Genocide is unavoidable, and arguably, not that bad.”

So, that’s the basic framework of the story out of the way. Now let’s get into why it’s bad—and to do that, we first have to say why Attack on Titan sometimes is actually really good, and fun to read, and I’m not being sarcastic here. A lot of people really enjoyed this series when it started, and all the way up till the ending showed what the story was really about, and I don’t blame them.

I myself had fun with this story often! Which is what makes it so much worse.

3. The Things Attack on Titan Does Well

When Attack on Titan came out, it got big, and it got big fast. To this day it’s one of the best-selling manga in the world, with over 100 million copies sold, and while the ending angered many, one can’t argue that this series, whether through the manga itself or through the incredibly popular anime adaptation, made a lot of noise. There are movies about Attack on Titan, books about Attack on Titan, videogames, a Marvel crossover. It’s not a series, it’s a media empire.

And we can be cynical about it if we want—but you don’t get this big without a modicum of quality.

So, yes, as I said earlier, Attack on Titan does a few things very, very well—especially at the start. I want to be fair in this review, and acting like the entirety of the series is badly executed, or that people who like the show have no media literacy, would be unfair. Attack on Titan gives you reasons to believe it’s a genuinely great show, up until it isn’t. I wouldn’t be surprised if a lot of my readers had at least watched the first season of the animated show, and had positive thoughts on it.

In that vein, then, here’s a list of all the things that, in my opinion, Attack on Titan does well.

- The very nature of the story, the ontological mystery at the center of it all, is well-executed. The hook is interesting, you want to know both what happened in the past, and what comes next. The story keeps throwing twists at you, past chapters keep getting recontextualized as we understand more about the world, and overall, the story is very dynamic.

-

The characters grow! They learn from their mistakes, and change, and make new interesting mistakes, and sometimes they die. Character interaction is the soul of Attack on Titan—early on, it turns itself into an ensemble cast story, and that was a good choice. You get invested in them, you learn to like them.

-

The action in Attack on Titan is horrific and trauma inducing, and some of its imagery is purposely grotesque. This makes it an effective tension-builder—as I said, people just die all the time—but this is juxtaposed with the more slice-of-lifey scenes that happen whenever we see the characters coexisting. These moments between big action setpieces act as a palate cleanser, and they also sell you that these people are human. They joke around, they can be genuinely funny, and they try to find levity in all the horror of their lives. Attack on Titan at its best is a story about people trying to live while they survive. Which in turn, of course, only makes the action more horrific.

-

The characters are distinct enough that you can tell them all apart both in looks and general character and motivation at a glance. Which sounds like not that big of a deal, but this is a series with a big cast, and it’s manga. So it is a big deal, actually. The art is stylistic, but it has strength and dynamism to it; seeing still images does it a disservice, because it really looks good when you read it all in a row.

-

There’s this character called Hange, and they’re nonbinary and also one of the main, most important characters, and a fan favorite. That’s kind of neat. The official translation uses they/them. They have a lot of shit going on, they’re not just defined by their lack of a binary gender, and that’s also pretty neat. Manga is an incredibly cisheteronormative medium, so it’s refreshing to see such a mainstream series have one of its best characters be trans.

-

Attack on Titan has a lot of jokes, and frankly, they can be real good. There’s an old piece of advice I stole from Ryukishi07 that I like to tell newbie writers—if you want your readers to cry for your characters, make them laugh first. Make the character fun, and funny, and entertaining to read about, and then your readers will develop an emotional link to said character. Kill them then, and see the tears flow. Attack on Titan does this, and it does it well.

- The worldbuilding is pretty cool up till a certain point. The way people kill titans—high-speed steam-powered parkour with swords—is just stupid enough that you roll with it. You’re like, yeah, yeah. I dig that. I dig it. It’s just visually effective enough that it works.

So that’s a pretty good list! Especially because so much of it is so general, and encompasses so much about the story. Shame, then, that all this good micro writing and well-paced, well-executed action scenes are in service of a thesis that is, legitimately, one of the worst things I’ve seen in a while.

4. Attack on Titan Has One of the Worst Theses I’ve Seen in a While

A thesis is, in few words, what a story is about. It’s the message communicated to the audience through the story and characters and setting. It’s the philosophical core of the story. I mentioned genocide earlier, and that is the thesis of Attack on Titan as of the last act. However, it also has a much more general thesis:

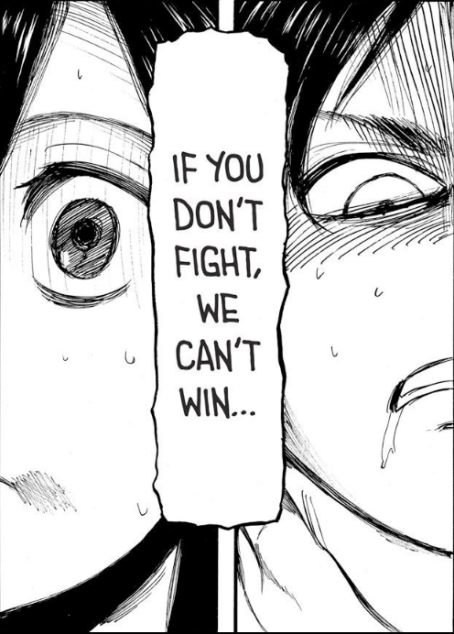

Attack on Titan is a story about violence, and the necessity of violence.

One of the very first things the series does is establish that titans are ruthless, and can’t be reasoned with. This is hammered home multiple times—no matter how much you plead, or what you do, or how you treat them, the titans will kill you as soon as they lay eyes on you.

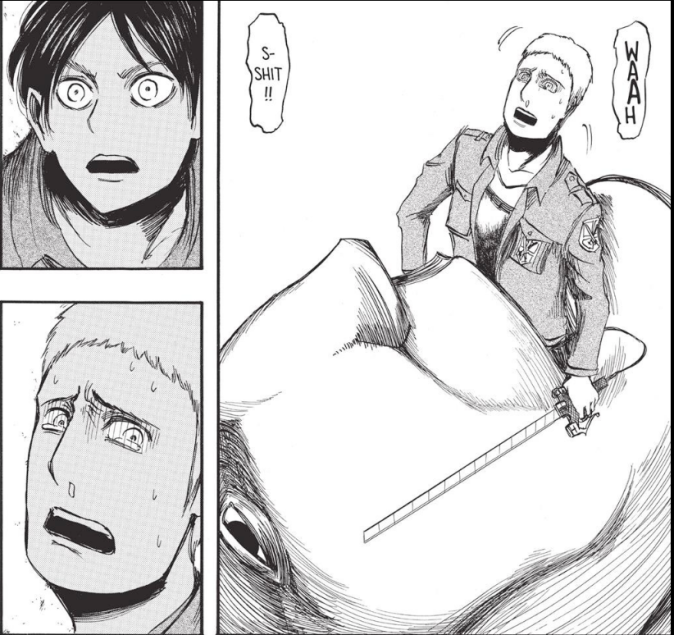

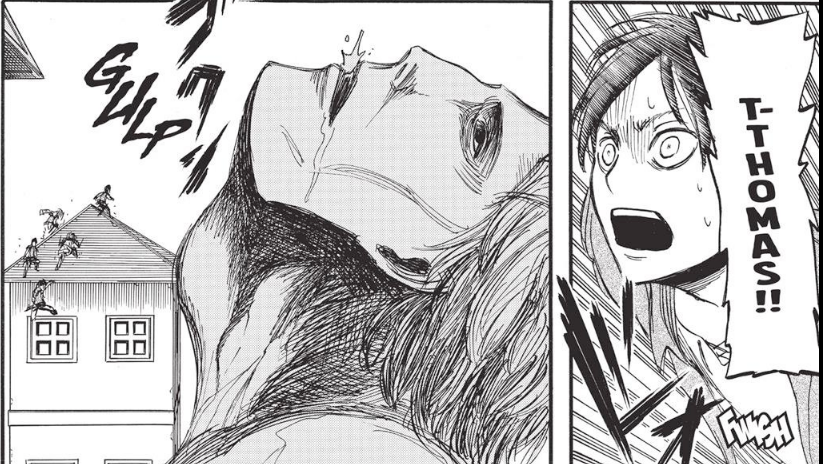

The death scenes are purposely ugly, visceral, and upsetting. Nobody keeps their cool whenever titans enter the picture, and the series takes grim glee in juxtaposing the peppy hero-like attitude of newbies before they fight their first titan, with the horrible things that happen to them once they actually fight. Titans represent a violent death, and nobody stays calm when faced with it.

These events happen in the span of of five pages. I counted!

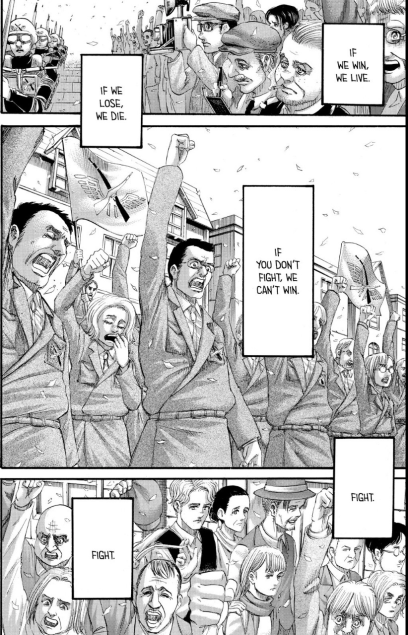

So the only way to deal with a titan is to kill it first. Anything else is suicide. Violence is necessary, because violence is inevitable, and you can only choose between being the victim or the victimizer?

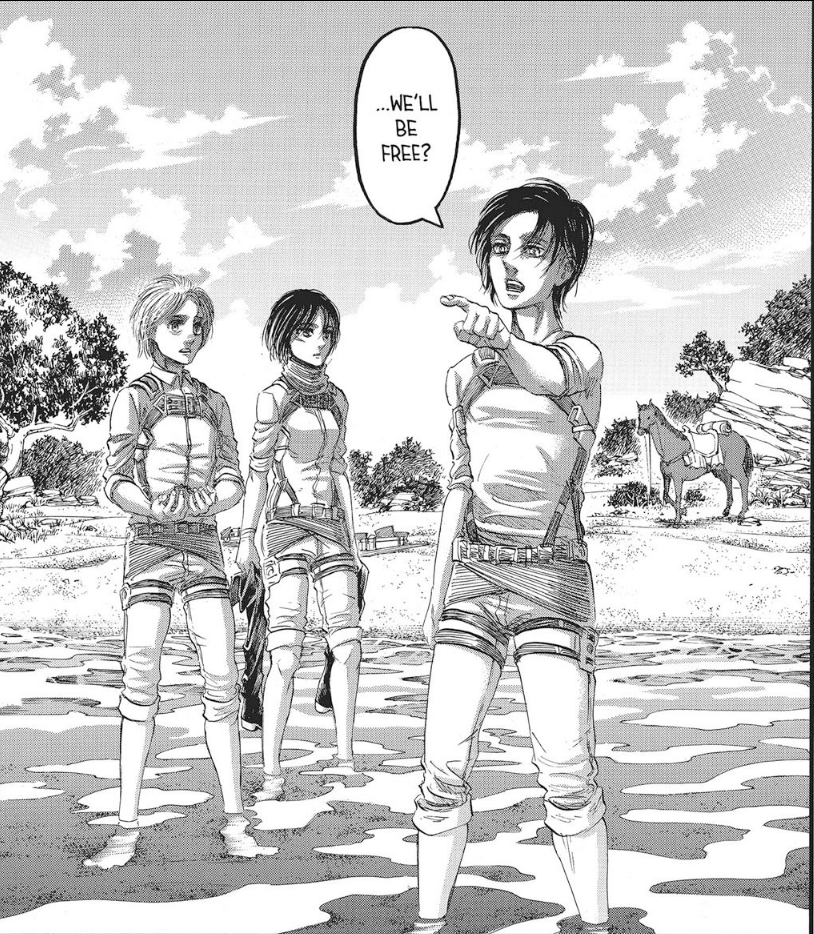

Do you want to be the hunter, or do you want to be the hunted?

So, there’s your answer. This is the story of Eren Hunter, who wants to kill all titans, because that’s the only way for humanity to survive: to destroy that which threatens you.

Now. War is a very common allegory in the fantasy genre. By making the abstract philosophical conflict of your story a literal one, the struggle is made explicit, and easier to understand. Famously, the big villain in Game of Thrones, the ice zombies, are an allegory for climate change; the author has the hero stabbing climate change to death to explain that we should try to avoid total ecological and environmental disaster.

Which means that, no, Attack on Titan is not a lesser series by having the characters fight the Other with swords and cool steampunk devices. That’s just a tool. It’s what the war represents that makes it icky—Game of Thrones has climate change as a threat, right? So what does Attack on Titan have? What do the titans represent?

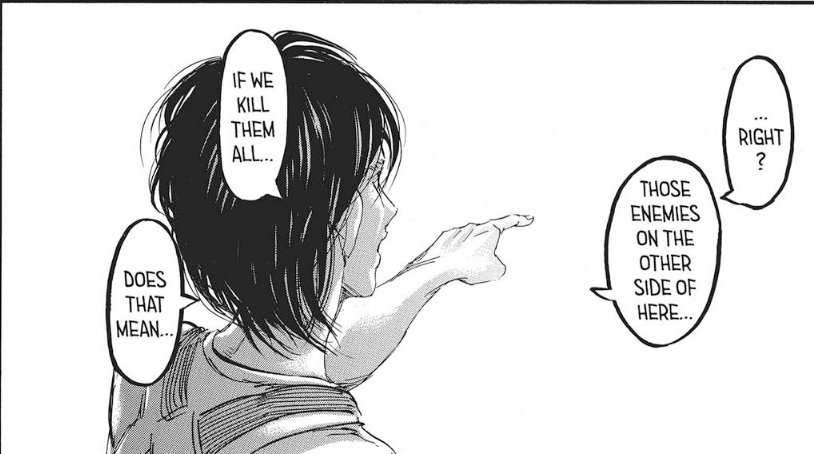

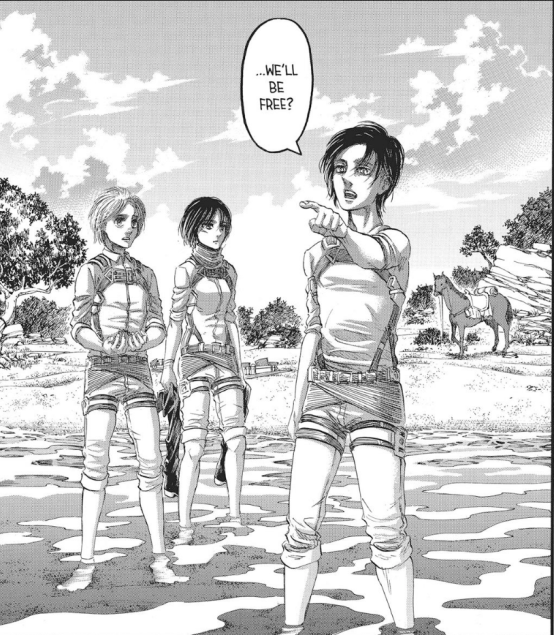

This isn’t clear from the get-go, which is why Attack on Titan can make such a good impression at the start. Eren Jaeger wants to be free, and his best friend wants to explore the world beyond the walls—so maybe the titans are the abstract threat of authoritarianism? Maybe they represent death?

What and who the titans are is one of the main mysteries, after all. You want to find out, you want to keep reading. And then, we’re told the answer, and the mystery behind the titans is revealed, and Attack on Titan shows us what the story is really about.

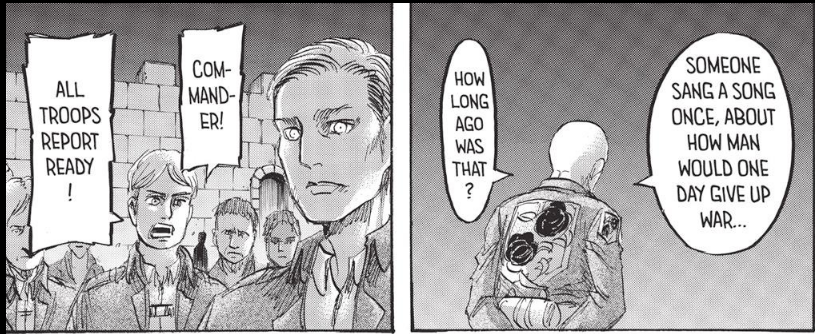

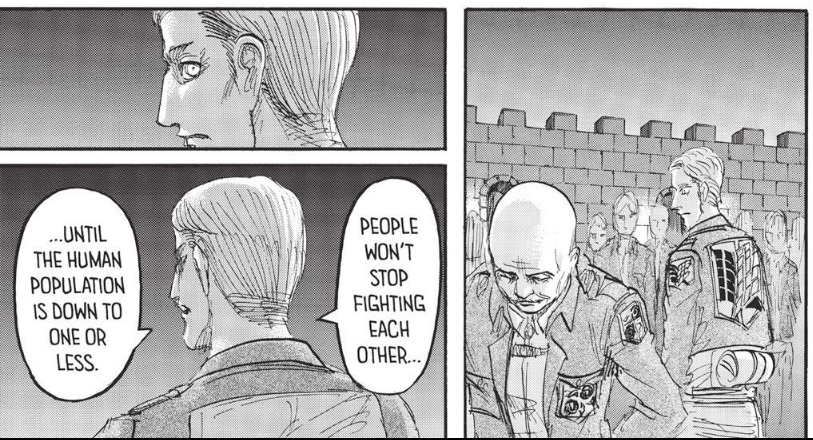

According to Attack on Titan, the biggest threat against humanity is humanity itself.

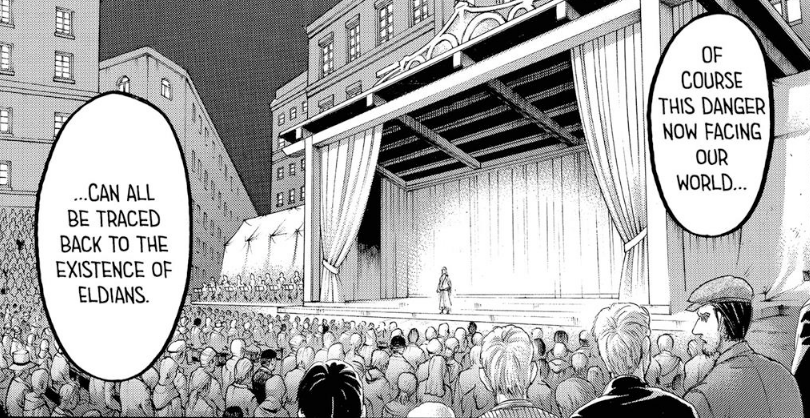

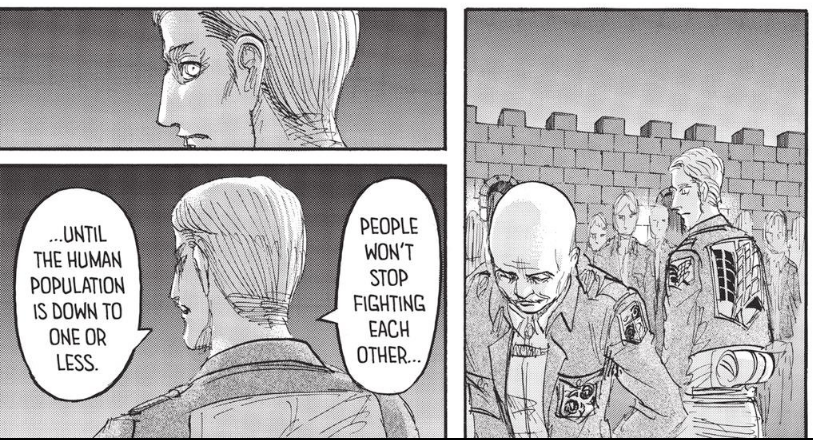

Mind, this is not me reading too much into the text. The titans are actual humans, they’re people who want us dead, and so we have to kill them first. Also, like, y’know.

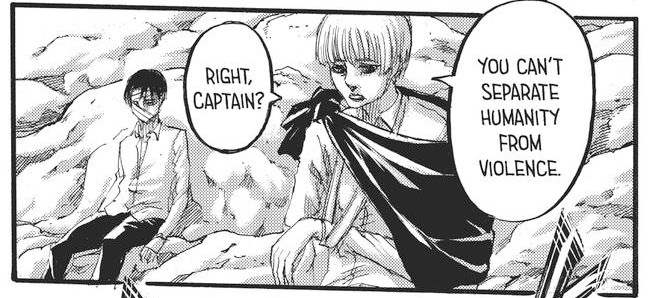

We’re just literally fucking told that humans are the real threat.

Like, out loud.

Like, it’s in the dialogue.

The thing about war, as an allegory, is that it’s reductive. It presents a conflict that is only solved through the destruction of the others. It works very well for certain conflicts—to go back to the earlier example, you can’t negotiate with the abstract conflict of climate change—but others, it has some Unfortunate Implications. Ursula K. Le Guin avoided the use of war as an allegory; she found it simplistic, and easy to misuse. To quote her directly:

Immature people crave and demand moral certainty: This is bad, this is good. Kids and adolescents struggle to find a sure moral foothold in this bewildering world; they long to feel they’re on the winning side, or at least a member of the team. To them, heroic fantasy may offer a vision of moral clarity. Unfortunately, the pretended Battle Between (unquestioned) Good and (unexamined) Evil obscures instead of clarifying, serving as a mere excuse for violence — as brainless, useless, and base as aggressive war in the real world.

If the actual threat that the war is representing is literally other people, humanity itself, then what we’re left with is a text that kind of… advocates for the necessity of genocide?

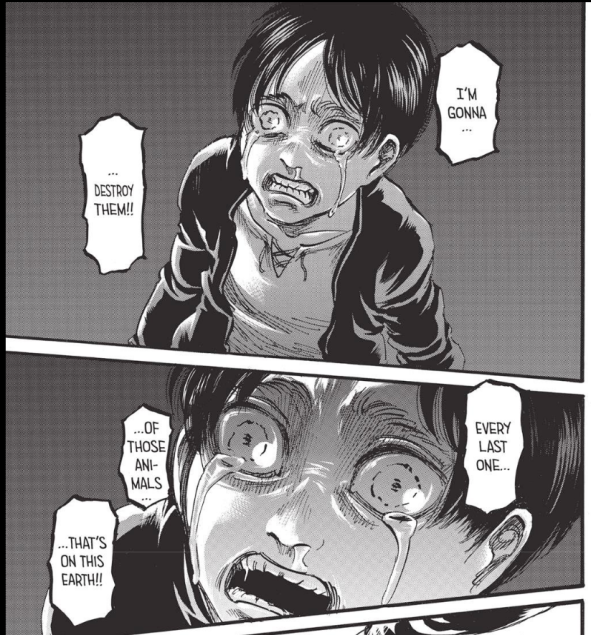

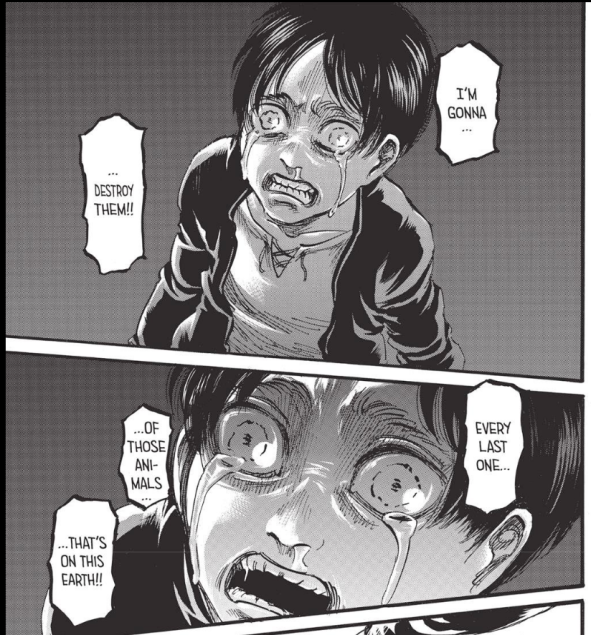

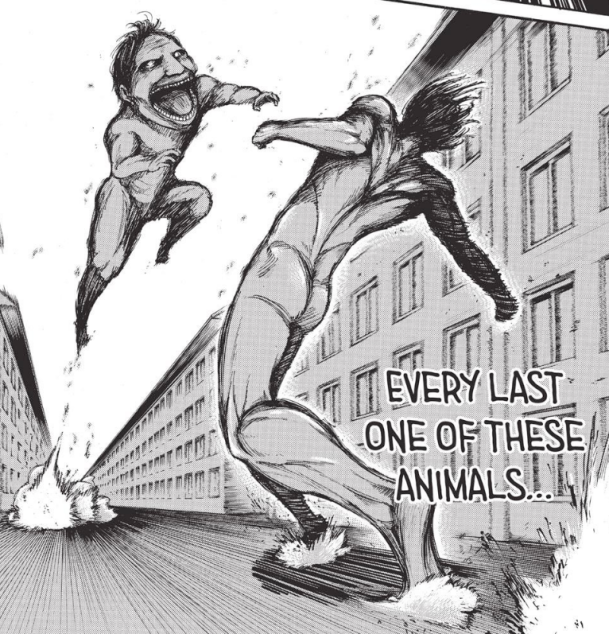

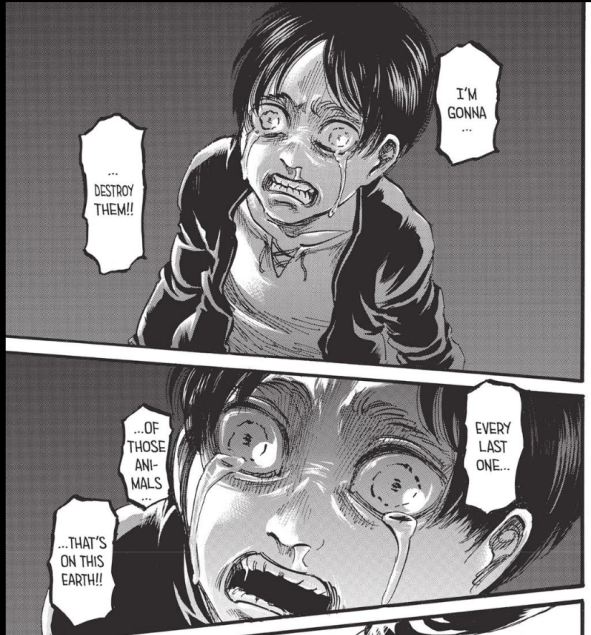

We repeatedly, constantly, get Eren saying that he wants to exterminate all titans. “I’m going to kill all of these animals” is something he says multiple times; the term extermination is used literally—and the story treats this as a good, correct goal to pursue. Then we learn that the titans are people, and controlled by other people, and Eren’s goal is to still exterminate them all.

The series keeps asking the same question—is violence necessary? And every time, the answer is yes.

Homo homini lupus. Fuck yeah.

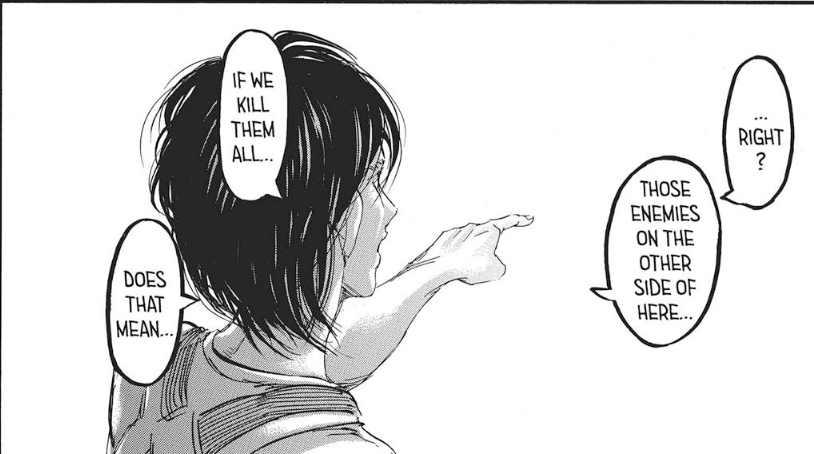

Now, the characters often talk about how they don’t want war. They repeatedly express that they want peace, that they don’t want to kill innocent people, that they want to talk with the enemies and find a civil solution to their conflict.

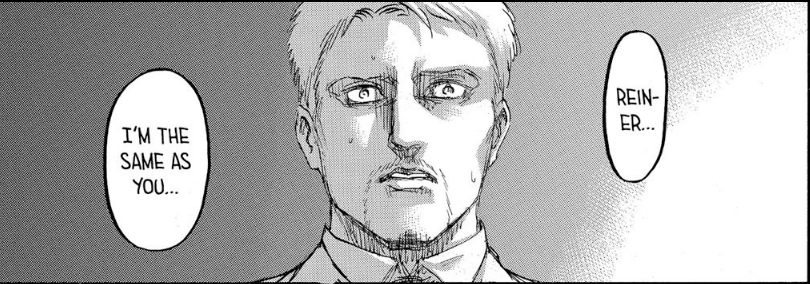

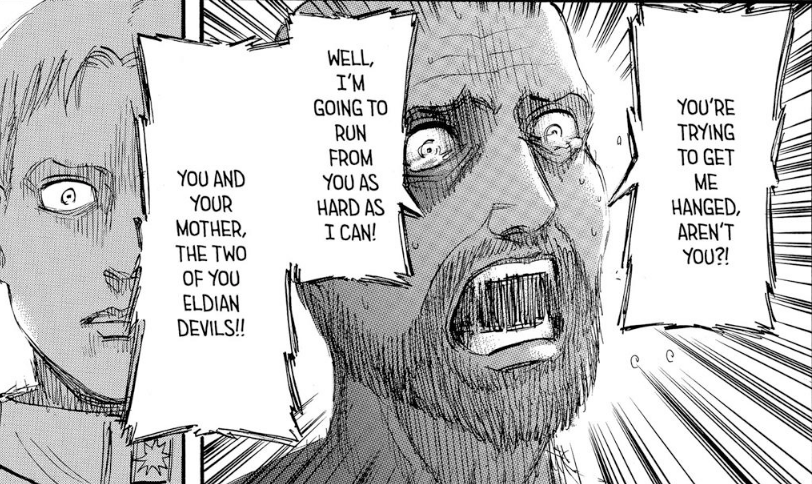

Every time, though, this is seen as a foolish dream at best, an actual show of cowardice at worst. There’s a couple moments where our main character himself recognizes that, actually, his enemies aren’t as different from him. Both times, this is immediately followed by him going “mind, I’m still killing all of you.”

One chapter later:

Eleven pages later:

Sure, the text of the story tells you war is bad, and the characters are convinced war is bad, but they also feel violence is the only real solution to any real problem. There’s simply too many evil people out there, too many cowards, too many traitors who will take any opportunity to kill you.

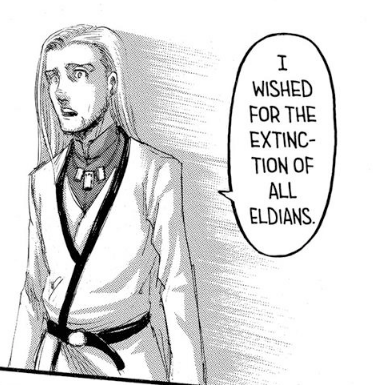

This culminates in the big final conflict of the series, exemplified by Eren Jaeger and his secret half-brother who can turn into a giant killer monkey: there are two solutions to the “titan problem”:

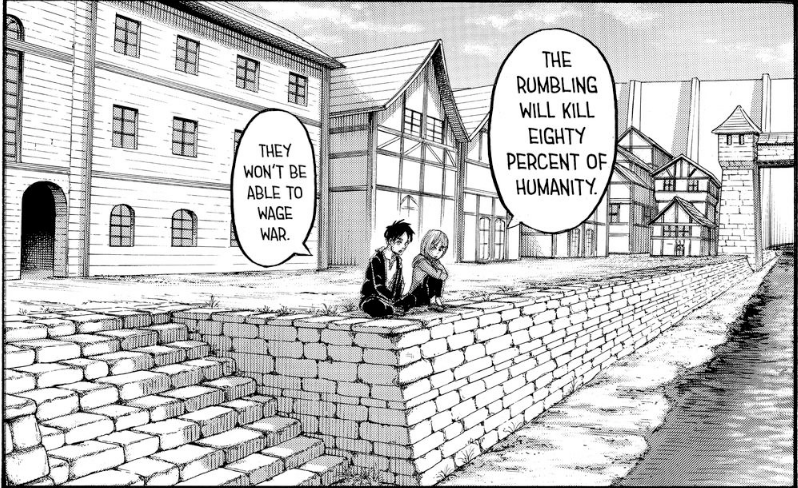

A) Genocide: we kill everyone outside of the island of Paradis.

B) Genocide: we forcefully sterilize everyone in the island of Paradis.

Eren wins.

And he feels bad about it!

But the narrative is like, nah, mate, you’re cool. You’re cool. If you hadn’t killed them all they wouldn’t have learned their lesson.

So, to reiterate: Attack on Titan is a story about violence, and the necessity of violence. Genocide, it says by the very end, is unavoidable, and arguably not that bad. It’s the only real way to find peace.

…Which, I mean, yeah. It’s not a good thesis. It’s one of the worst theses I’ve seen, from a simple moral standpoint, because it basically says that—I mean, this is advocating for genocide. This is just straight up advocating for genocide as the only way to solve a large-scale problem.

But that’s not the only reason why the thesis is bad. I do oppose this thesis morally, but also on a purely literary level—because the thesis informs the rest of Attack on Titan, right? It’s what the story is about, it affects everything else in the story.

It completely fucks up the characters. To give you an example.

5. The Characters

Escalation is a common problem in manga; it’s almost a staple of the medium that, as a series keeps going, the stakes will get higher and higher, and never stop. Ultimately, threats are so large in scale, it’s ridiculous—every enemy is ten times stronger than the last, every explosion is ten times bigger, etcetera—and the first few chapters look quaint in comparison.

It’s an endemic problem, one that takes away from the legitimacy of manga as an artistic medium for many people, and a symptom of the despicable working conditions manga authors are expected to live through. When your schedule looks like this, it’s absolutely natural that your storytelling abilities will suffer; and long-term planning will go out the window because you need to meet your deadline every week, and you have no time to think or plan or rest, and you’re operating on three hours of sleep. Constantly.

Which means that yes, actually, manga and anime are often really fucking bad because of capitalism. That’s the reason why we’ve got so much fucking disgusting fanservice, often of the underage kind, so—y’know. Gift that keeps on giving. Thanks, Adam Smith. Really cool.

Anyway; badly-handled escalation happens to Attack on Titan, too. But unlike with other popular shows that suffer from this problem, obvious examples being Naruto and Bleach, Attack on Titan doesn’t make it a structural problem. It affects the characters.

See—because the thesis of the story is that violence is necessary, any threat has to be blown out of proportion, any kind of attack has to be shocking and visceral and sad. Because, if you do that, the characters going into a killer frenzy, glorifying rage and hatred and violence as a response, feels not only justified, but cathartic.

And at first this is easy to do. I already mentioned the juxtaposition of slice-of-life segments with gruesome violence, using whiplash to enhance the emotional reaction to the gore. But, remember when I talked about Eren turning into a titan, early on? How that changed the entire vibe of the story?

Yeah. Here’s where that really starts biting Attack on Titan in the ass.

Because so far, titans have been such an impossible threat, where just a single one of them could kill an entire army of specially-trained soldiers with top-notch equipment. Only, if Eren himself is a titan, there’s no real threat against him, is there? He can Jackie Chan his way out of a fight. No human can do anything about it. The stakes go out of the window.

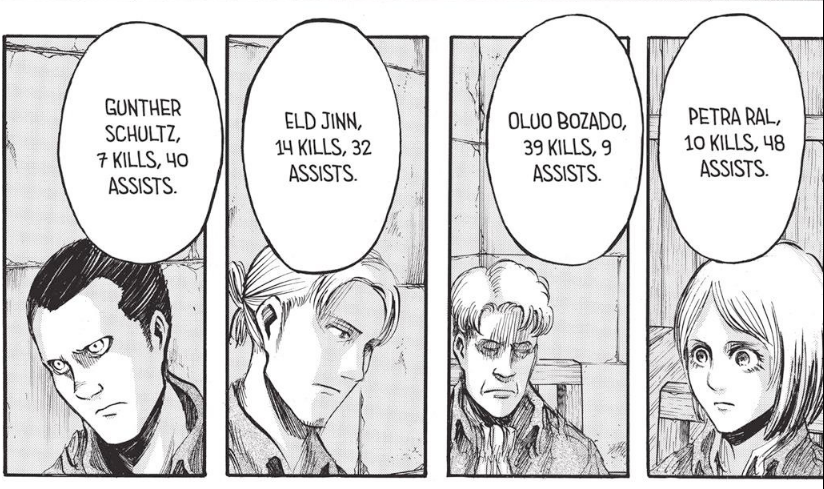

So the series goes, no, actually, there are some soldiers who can absolutely kill Eren. Turns out that titans aren’t that much of a threat. Enter the Levi Squad.

The Levi Squad, named after their leader Rivaille, are a group of elite super soldiers that specialize in killing titans. Rivaille is the strongest soldier humanity has to offer, and there’s an entire chapter dedicated to convincing the government that he can totally take Eren in a fight.

Out goes the hopeless vibe of the story. Normal titans just don’t cut it anymore—to make it so Eren can be threatened or dealt with, the series tries to claim it’s been exaggerating the danger of the titans. If you have the right equipment and treatment, they’re easy to deal with.

But this completely robs the story of that visceral feeling it wants to keep. So the titans have to become more powerful, too; they have to be such a threat that the only solution is total extermination.

Enter the special titans.

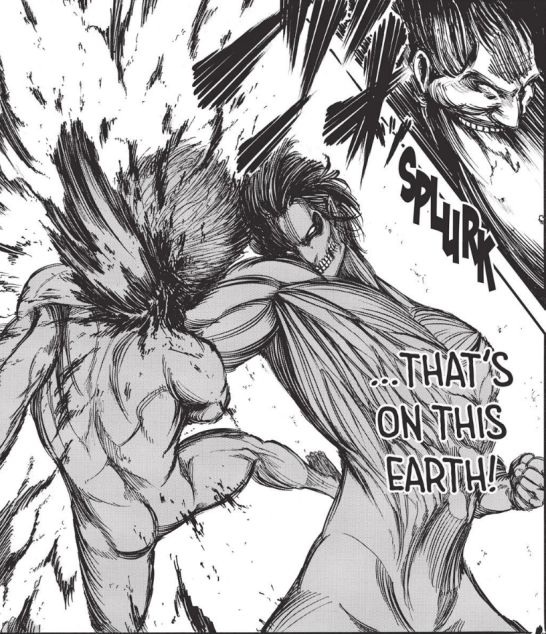

And exit the Levi squad.

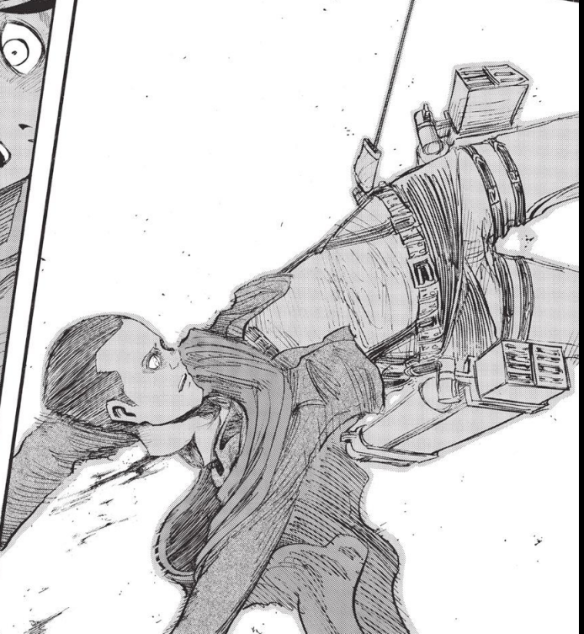

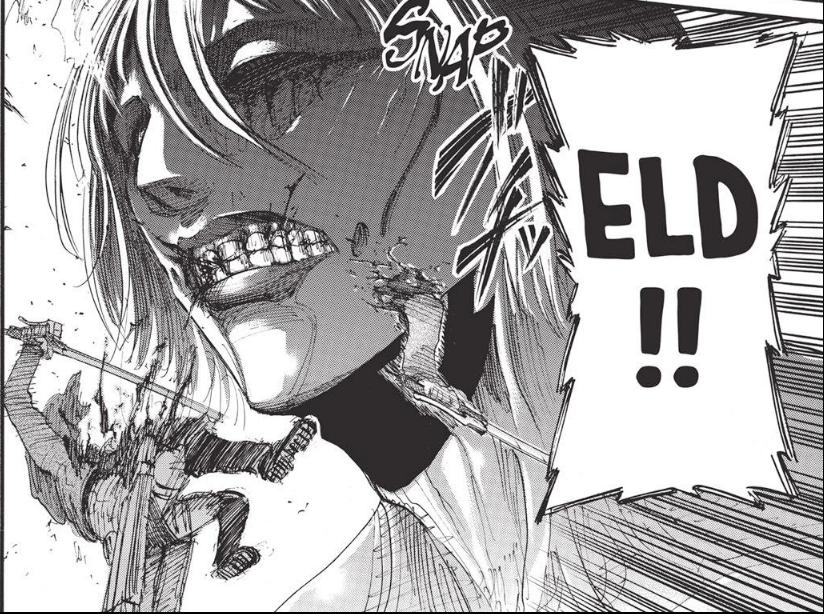

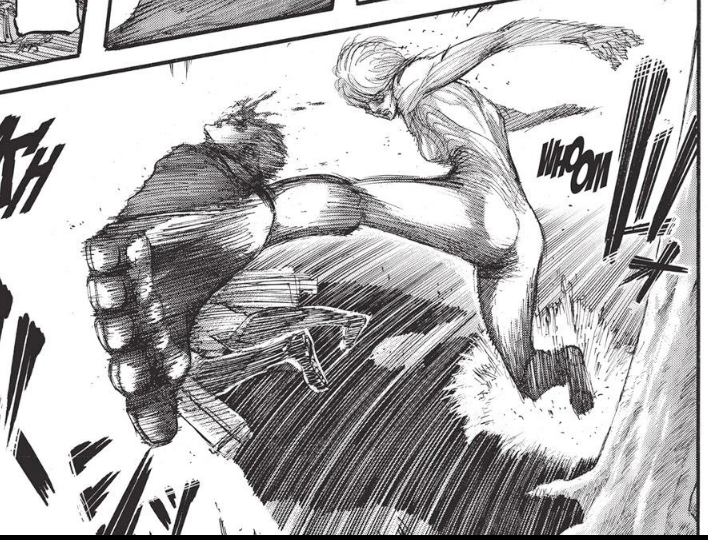

There, hopeless vibe restored. The Levi Squad is presented as an incredibly strong group of soldiers, as a way for humanity to take back what’s theirs—and then one titan with a blonde wig pops up and they all die incredibly gruesome deaths. It’s an effective moment, because we’ve gotten to know Levi’s Squad by this point, we’ve been shown what they’re capable of, we’ve come to trust they’ll stay alive.

So, this is actually pretty good. All this stuff I’ve told you about? This is good writing! It’s effective! It’s such a memorable moment.

And it completely makes Attack on Titan a worse series in the long run.

Because, first of all, this is not the only time it happens. Every time the humans manage to win anything, an even more fucked-up titan appears and wrecks shit galore. It’s a whole thing.

But these aren’t mindless titans, they’re not monsters—they’re titan-shifters, humans like Eren who can turn into a titan at will but keep their intelligence, morals, and motivations. They’re full three-dimensional characters with complex backstories that we later get to explore; most of them are victims of discrimination in their home country, and have been raised as child soldiers for a cause that involves killing their own people.

We learn this later, though. Way later. First thing we see is them gleefully torturing innocents for fun, and then laughing about it.

Because the story has to restate, as often and as strongly as possible, that titans are the worst blight humanity has suffered. For violence to be necessary, any other solution is deemed impossible; negotiation won’t get you anywhere, dialogue is not an option, common understanding is impossible. The titans are either mindless and won’t listen to reason, or they’re intelligent, and they use that intelligence to inflict more pain when they kill you.

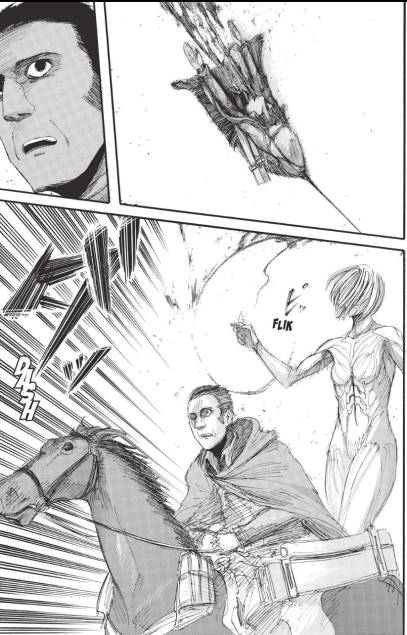

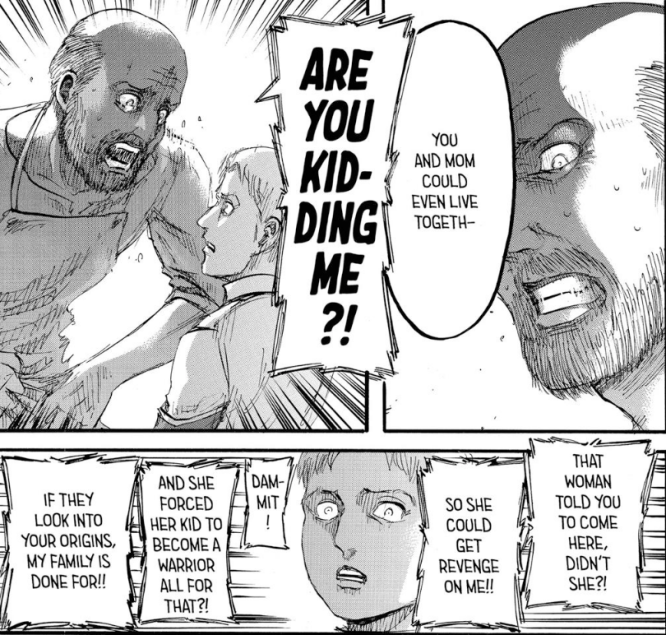

It’s all about the escalation. The threat has to continuously be bigger. As the heroes learn new ways to deal with titans, the titans need to get more ruthless, more villainous. When characters reference this:

You, the reader, can’t just agree. You need to enthusiastically agree. You need to feel it in your bones.

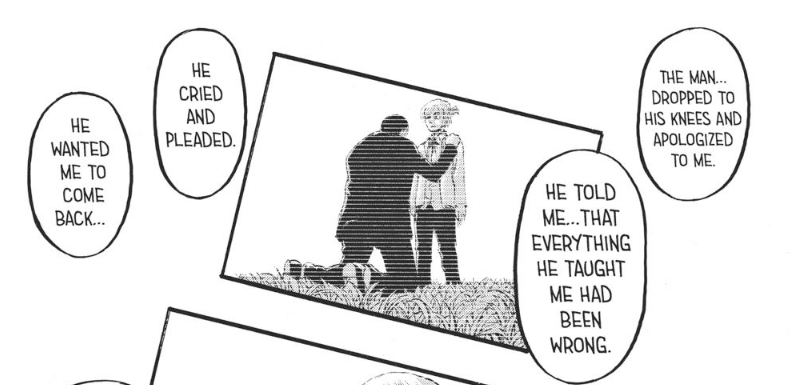

Imagine how awkward, then, when later in the series, these characters are supposed to be allies, misguided innocents all along. They join the heroes, and show that all this time, they had such a heightened sense of empathy. They want to put an end to the war, too.

And the rest of the characters forgive them immediately. There’s other people to kill, anyhow. We gotta move on. Don’t think too much about it.

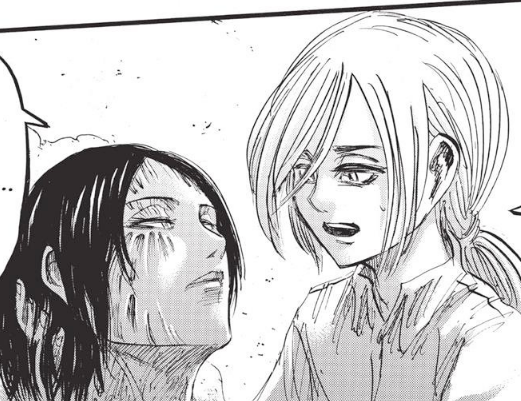

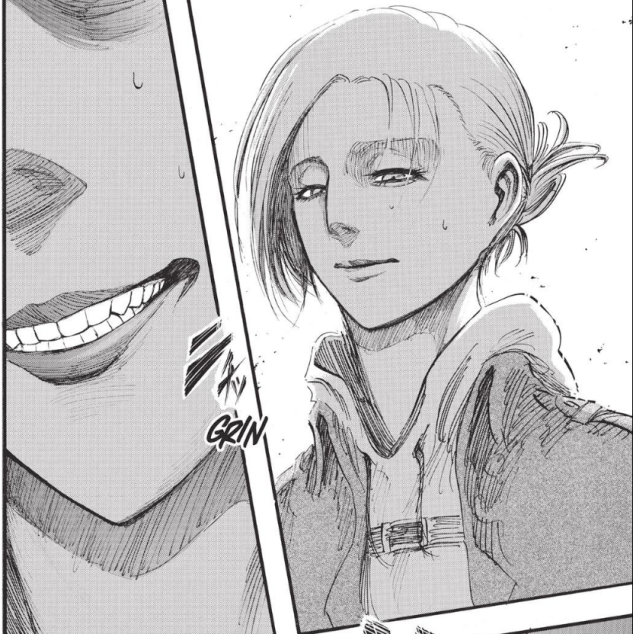

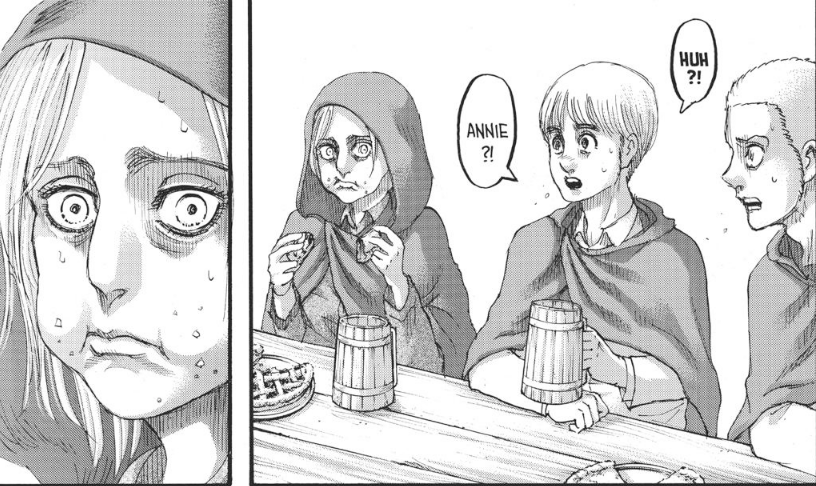

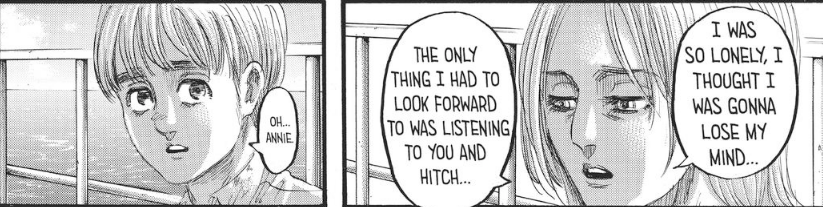

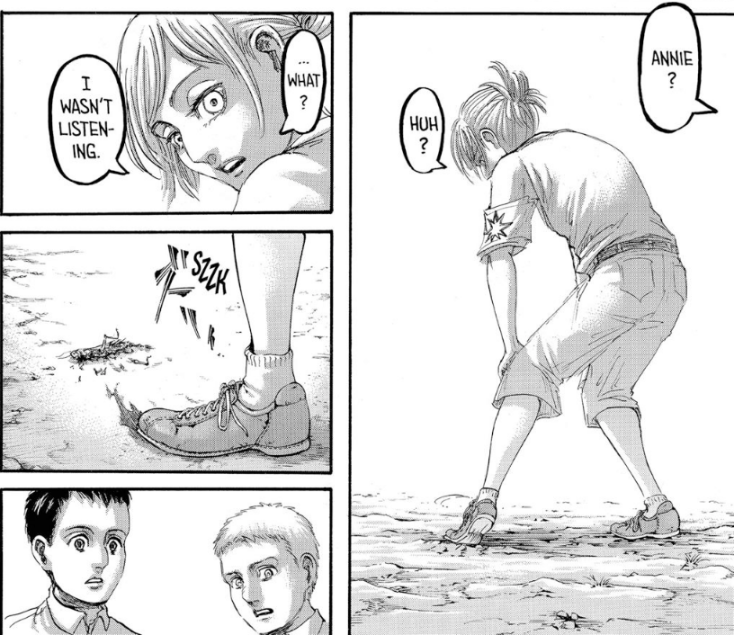

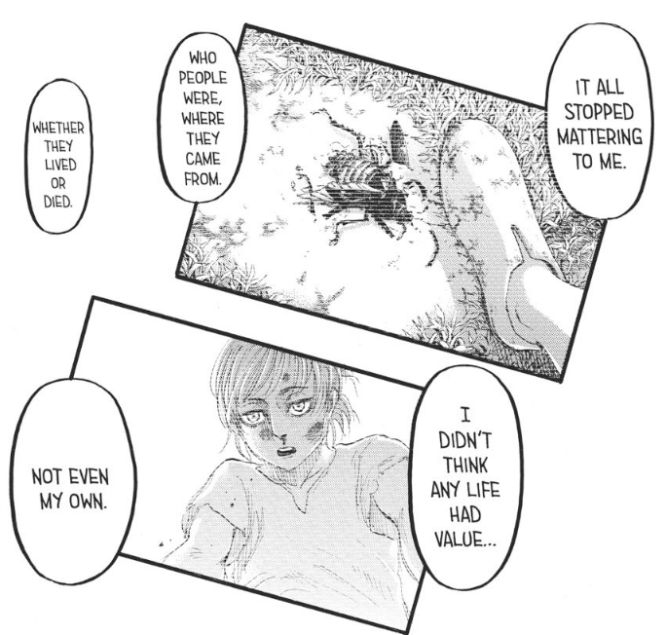

It’s jarring. I can’t stress enough just how baffling it is to read. How silly it feels to have Annie, a character whose very last scene before the timeskip involved this:

Be reintroduced to the very same characters like this:

She has a little intro before this where she’s played as a bit of a threat? She has a knife! She means business! And then it’s like, oh, look at her! She was just hungry! Laugh track, continue the story, never reference all the stuff she did. Some characters do point out that she’s getting off easy, but the narrative clearly frames them as hot-headed and in the wrong. Move on, it says. That doesn’t matter.

This is not just bad planning, though. This is all in service of the thesis.

Listen, Attack on Titan wants to make it clear that violence is necessary. It presents a world where every conflict can only be solved by adopting an us versus them mentality. Anything outside this very strict worldview is either wrong, or a recipe for failure—this is hammered home one, two, twenty, a hundred times.

The problem here is, then, that as the series goes on, the framing of who’s us and who’s them changes. The “them” is, at first conceptualized as the general threat of the titans, plural. Titan shifters count as titans, so they’re pure evil incarnate, and you can only kill them or be killed. They torture innocents, have no mercy, and, just.

Just.

But once the second paradigm shift in the story is reached, and they discover there’s a world outside the walls who hates them, those are the real enemies. Not the titans, but actually, the people outside of their island—the people of any race but their own, those who can’t turn into titans. People who can turn into titans are good, actually. They’re one of us.

It doesn’t matter what they did. It doesn’t matter what they’re like. What matters is, it’s us versus them, and anything outside of this worldview is wrong.

So, yes. Annie is good, actually. Ignore that whole “laughing at the horrible way in which she murders people” thing. That monkey I keep posting, too—that guy is later revealed to be a psycho, sure, but a completely different brand of psycho, and the way in which he takes glee killing people horribly goes against his entire later characterization.

His name is Zeke. He’s Eren’s secret royal half-brother, and wants to commit a slightly different kind of genocide, which the series calls “The Euthanasia Plan”, and it involves forced sterilization, and no euthanasia whatsoever. But at this point, you know, like. Whatever.

For violence to be necessary, it has to feel both justified and inevitable. This involves the enemy being ruthless, evil, monstrous—but it also requires a sense of purity to come from the good guys. They need to be noble, they need to be innocent or deserving of protection, so that their deaths are seen as particularly horrendous. The only way to defend them is violence, and so, that’s what you use.

But this is such an absolute, strict rule, it’s so fundamental for the thesis, that the series sacrifices characters in its service. It doesn’t matter what Annie or Zeke or Reiner were at the start of the series. They need to be good guys by the end. They’re us. Fighting against them. That’s all that matters.

What’s that quote from Ursula K. LeGuin I referenced earlier, again?

Immature people crave and demand moral certainty: This is bad, this is good. Kids and adolescents struggle to find a sure moral foothold in this bewildering world; they long to feel they’re on the winning side, or at least a member of the team. To them, heroic fantasy may offer a vision of moral clarity. Unfortunately, the pretended Battle Between (unquestioned) Good and (unexamined) Evil obscures instead of clarifying, serving as a mere excuse for violence — as brainless, useless, and base as aggressive war in the real world.

Yeah.

So now that we’ve talked characters in general, let’s talk about female characters in particular. Because Attack on Titan is incredibly, horrendously, misogynistic.

And we’re talking about manga here, so like, even by those standards. Yeah. Get ready.

6. The Female Characters

The big issue with all the women in Attack on Titan, if we’re going by the broadest of strokes, is easy to explain. It goes like this:

-

They’re irrelevant to the plot.

-

They’re defined by the men around them.

The first point is easy to see, especially once the series is over. While you’re reading it you can’t really tell where a lot of the character arcs are going—and there’s enough women in the cast that you assume at least one will end up doing anything remotely important.

That doesn’t happen, though. In Attack on Titan, men make choices, and women stand by and watch. Sometimes they execute the plans that men have drafted up, but they make sure to follow strict orders; they’re cripplingly devoid of any personality. Delete every female character from Attack on Titan in the last 20 chapters or so, and there’ll be no real changes to the storyline—and in a character-based supernatural drama, that’s a huge red flag.

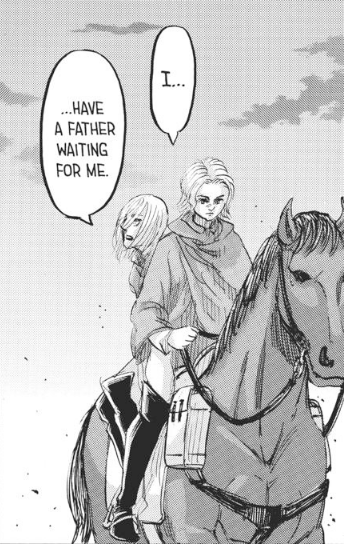

But it’s the second point that really drives it home for me—mostly because the fact women in Attack on Titan are defined and limited by the men they devote themselves to is the reason they’re so irrelevant. A male character’s goal by the end of the series is to save the world and ensure a future for humanity; a woman’s motivation is to marry, have children, and maybe ask their daddy for a hug.

In a series that deals with the necessity of violence and the horrors of death, having characters crave mundanity could have been a statement. To want something incompatible with violence.

It’s just that it’s literally only the women who do this, and it always involves a man. The “ask daddy for a hug” bit is not me being facetious; that’s literally Annie’s entire motivation by the end of the story.

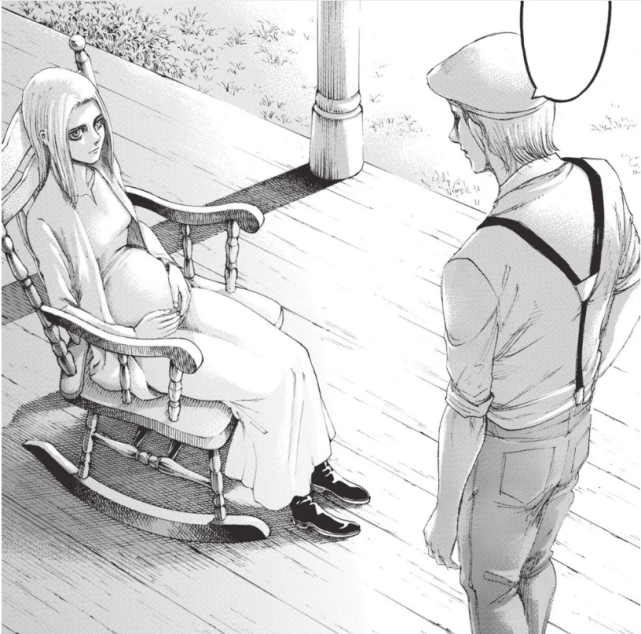

Okay, no, that’s slightly wrong—she’s also someone else’s romantic interest. They have a subplot about that, and it looks like this:

Eleven pages ago:

Every main female character is someone else’s romantic interest, with the sole exception of two late-comers: Yelena, who literally disappears halfway through the ending because the author forgot about her, and Pieck, who just sort of exists. There’s even a woman who’s been with the cast from the beginning—Sasha Braun; if you have never watched Attack on Titan but are aware of the memes, she’s the potato girl. She’s retroactively given a boyfriend after her unceremonious death, so he can have a character arc.

Pieck as a character is fascinating because she does nothing, then has a cool moment in which she’s utterly dominated by Eren, then she does nothing, and then the series ends. She’s a fan favorite, though, because the fandom is unspeakably horny for her. There’s a porn subreddit for Attack on Titan, named r/AttackonTitties, and I had to look up tutorials on how to get my phone to show me NSFW stuff on reddit to find it. It felt oddly humiliating, but at least I managed to prove my point: r/AttackonTitan is mostly about Pieck’s ass.

As a side note, by the way—there’s a bit of a Smurfette thing going on with Annie, the Female Titan? To start with, her name is literally “THE Female Titan,” implying there’s only one. Other special titans all have a superpower that defines them (they can create armor, they’re very big, etc) but as far as we know, the Female Titan’s only superpower is that she’s got boobs.

So male-looking titans are the standard, and female-looking titans are such a rarity that one character mentions he’s been wanting to be vored by “a pretty titan lady” for decades. This is not a joke, this is a thing that happens. The name’s Commander Pixis, you can look it up.

Either way, this gets somewhat addressed later on but very sloppily. We’re shown other women who are titan-shifters, and titans who were women once, but once they turn into monsters they all look male, because again, Attack on Titan acts as if being a man is the standard. As per the Female Titan, while she maintains her stupid title, the show retcons her some superpowers. Turns out she can copy other titans’ special abilities. This adds nothing to the plot and raises at least two more plot holes that I’m aware of. So, y’know, good series, very progressive.

Annie’s taciturn, doesn’t talk much, she waits for other people to tell her what to do—mostly so she can snark about it, then obey anyway. It’s implied she’s got more going on, and that we’ll understand her better once we learn her backstory. Only we don’t learn her backstory. She’s got none.

We learn Reiner’s backstory, though, Reiner being a character who has the exact same narrative role as Annie but he’s a man, so he’s more important. We follow him for half of the story, and Annie is, sometimes, in the background. It’s truly bizarre, actually, because both Annie and Reiner are in the show from the start, and the fact that they’re traitors—they come from outside of Paradis, and are actively working against the protagonists, and kill some of their friends—is this huge twist that turns the story inside out.

Only, it’s Annie who’s built up. She teaches Eren how to fight, so they’ve got a student-master thing going on, and we learn some world-building by having her cast doubts on the Paradis government. Annie is then revealed to be a traitor, and immediately turns into a crystal—long, boring story; you don’t care—which means she vanishes from the story completely.

Then fucking Reiner, who I swear to god has been silently standing by the corner for thirty chapters by this point, is suddenly given this entire backstory we never heard of—and we’re told, not shown, that Eren looks up to him, that they’ve got this huge student-master thing going on, that he’s incredibly important for our main cast. He’s also revealed to be a traitor—exact same structure to the reveal as Annie’s, even; beat by beat—but then he gets to carry the rest of the plot.

So we get the exact same reveal and the same beats twice in a row. Annie’s doing stuff, and then the story goes “wait, no, something’s wrong,” pauses, does it again with a guy in her stead, and goes “phew, that’s so much better.”

Reiner is given entire chapters about his psyche and how he feels about killing the people he’s called ‘friends’ for years. It gets to the point where the wiki calls him “the main protagonist of Attack on Titan from the (non-Paradis) perspective. The first time I read Attack on Titan, I had no idea who he was when we’re told he’s a traitor. I had to Google it.

Annie is only important when Reiner talks to her. He’s like, what the fuck’s up with you. She goes, idk, I’ve got a dad, I guess. I’m very taciturn. I kill stuff.

Zero depth to this. In a striking bout of irony, Reiner also has daddy issues, and those are actually shown and explained, but he doesn’t really seem to give a shit. He’s busy having actual motivations.

The funniest thing about this is that Annie isn’t even the worst example, because the deuteragonist of Attack on Titan, named Mikasa, is basically Annie but with black hair: taciturn, serious, waits for orders, sometimes snarks.

We see a little bit more of Mikasa’s backstory—only, it’s completely focused on Eren, the guy who will later commit genocide. Eren saved Mikasa from child trafficking when they were eight years old. We see that scene from her point of view, but the focus is absolutely, one hundred percent, on Eren. It’s all about how he makes the choice to fight, and how he inspires her to fight under his command.

Mikasa is then adopted by Eren’s family. Which means that they’re siblings, yes, but they’re not related by blood, and this is going exactly where you think it’s going.

Mikasa is hopelessly in love with Eren. Basically everything she does, she does it to protect, please, or save Eren. That’s her entire deal.

There are implications there’s more to her. She’s incredibly strong, and there are hints it’s because of her ancestry. Then it’s implied she’s superhuman, or from a different race. Then it’s implied her constant headaches are because she’s got some supernatural bond with Eren.

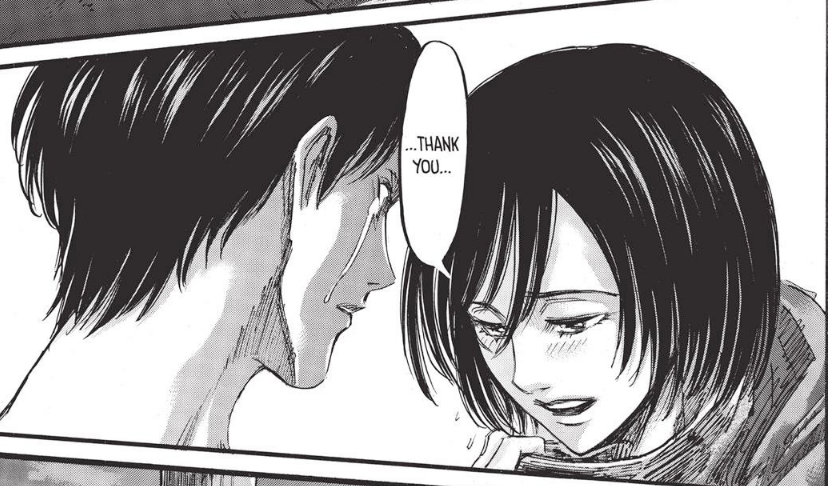

Literally none of the things I said impact the story, there’s nothing else to Mikasa, and the headaches were just headaches. Eren carries the plot; Mikasa reacts. No initiative. She does oppose Eren’s genocide, and you would think that’d be a conflict—but every single one of Eren’s friends opposes the genocide. No special emphasis is given on Mikasa; we instead focus on the men. She doesn’t talk much about it.

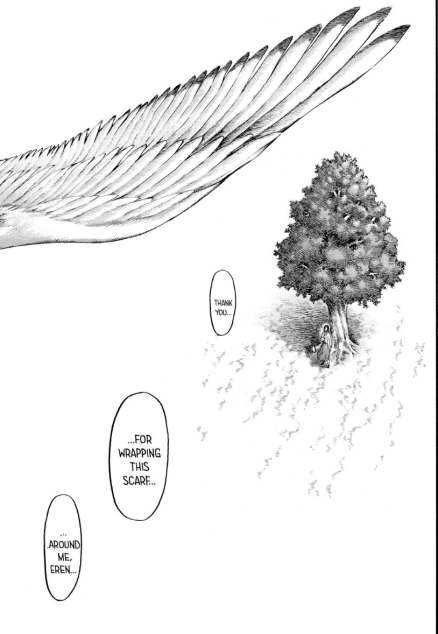

She’s the one who kills Eren, though, because she is—again—very, very strong. Here’s what she does right after:

And here’s how the series ends:

She does nothing. You can erase her from the story and nothing changes.

Then there’s this other female character—very cute, very kind, very clearly represents humanity’s best half. Her name is literally fucking Christa, no, I’m not kidding you, they do that.

Then it’s revealed Christa has a dark backstory. She’s related to the royal family of Paradis—she’s the true heir to the throne!—and she’s got access to the island’s secret history, and her real name is literally fucking Historia, and again, no, I’m not kidding you, they really do that.

Anyway! Historia has a personality. She’s fighty and jaded, she can joke around but is burdened by her horrible childhood—she got bullied to hell and back, and her mom was a bastard—and she wants to live and tell everyone to fuck off, let her rage out. She’s kind as a self-defense mechanism, because life has been horrible, and being liked is a surefire way to avoid getting hurt.

There’s an entire arc where she’s the main focus, and then she’s crowned Queen behind the Walls. Plot-wise, she shapes up to be one of the most important characters in the story.

She disappears for like twenty chapters.

She reappears after the timeskip, pregnant and miserable.

Her husband is, we’re told, one of the kids who threw stones at her. No, he doesn’t get a name. No, we never see these two interacting. We don’t even see this guy’s face.

Historia then does absolutely nothing. She only talks one more time in the entire story; it’s in a flashback, and she talks to Eren—and the focus of the scene is squarely on Eren.

This one is so painful, it’s built up in such a prominent way only to then do absolutely nothing, that I’ve still to see a single fan defending it. The way the story completely drags this character through the mud by the end would be more infuriating if it weren’t so incredibly baffling. Entire subplots about her that aren’t even mentioned in the ending. It’s not even like the writer forgot—it’s like he literally stopped writing.

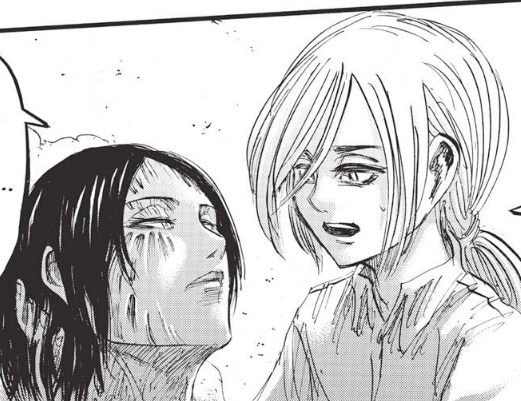

Small note: remember the lesbians? The ones I mentioned last time?

Yeah, one of them was Historia! The girl next to her, called Ymir, starts as a taciturn character who snarks but ultimately follows ord—okay you know the deal. Ymir has a very strong bond with Historia, and it’s extremely implied that they’re in love. There are a lot of talks about how they love each other, how Ymir wants to marry Historia, how they’ll escape and live together, etcetera.

Also, there’s this:

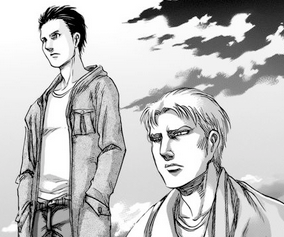

The dude she’s talking to? That’s Reiner! Male Annie! His love interest is Berthold, a character that—okay, to be honest, these two have no chemistry together. Still, y’know. Cool to have this!

Ymir is revealed to be a titan, and Reiner carries her away from Paradis. She’s never seen after that. Much later, we’re told Ymir died off-screen, and she’s literally never brought up again. Historia thinks about her once, when she gets a letter, and then gets pregnant.

(Berthold has a more plot-relevant death, but he still, absolutely, dies).

Here’s where it gets fucked, though. This one will be quick, because, to be entirely honest, it’s repugnant—and I don’t want to make fun of it. I just want to point out how bad it is.

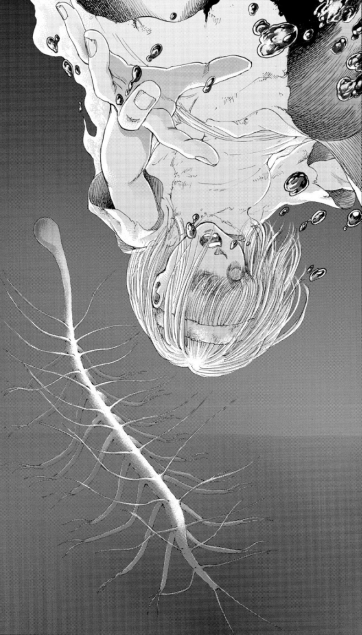

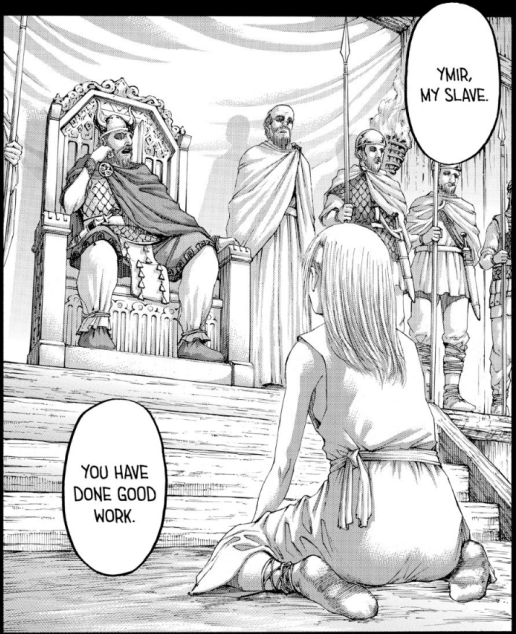

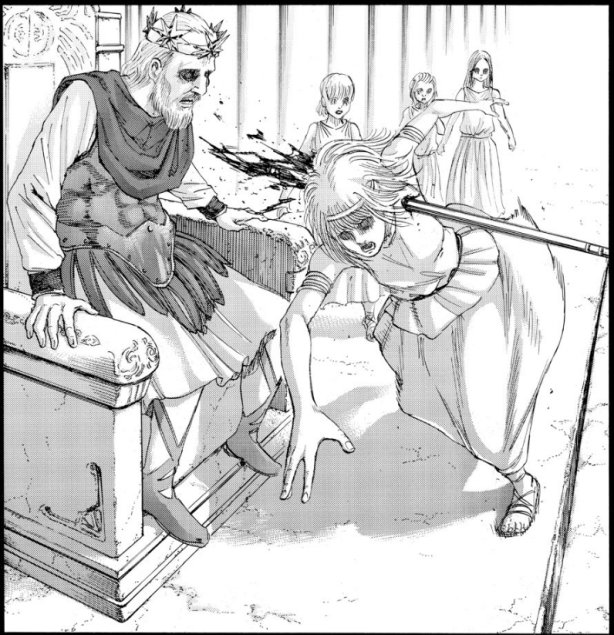

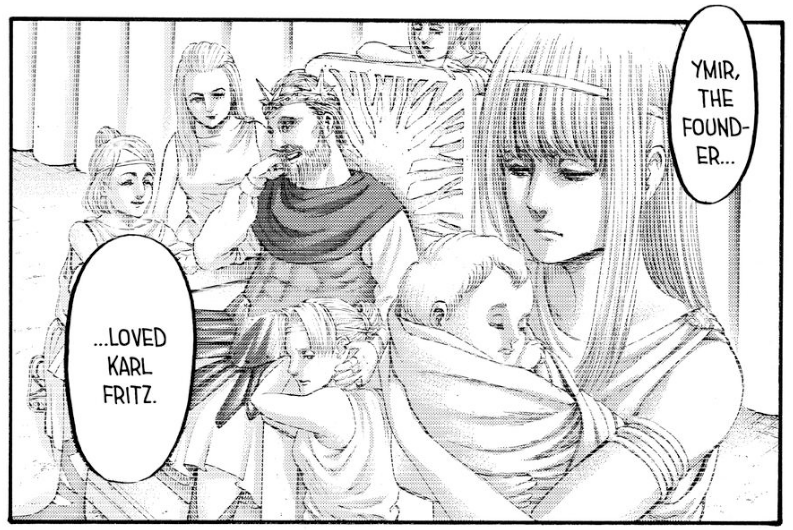

Ymir, the lesbian, shares her name with Ymir, the first titan. Ymir (old) was a child slave who got in contact with an alien, and that’s why she became a titan.

The king of the island took notice of this, and since Ymir was his slave, he started giving her orders, telling her what to do, which enemies to kill. Ymir obeyed.

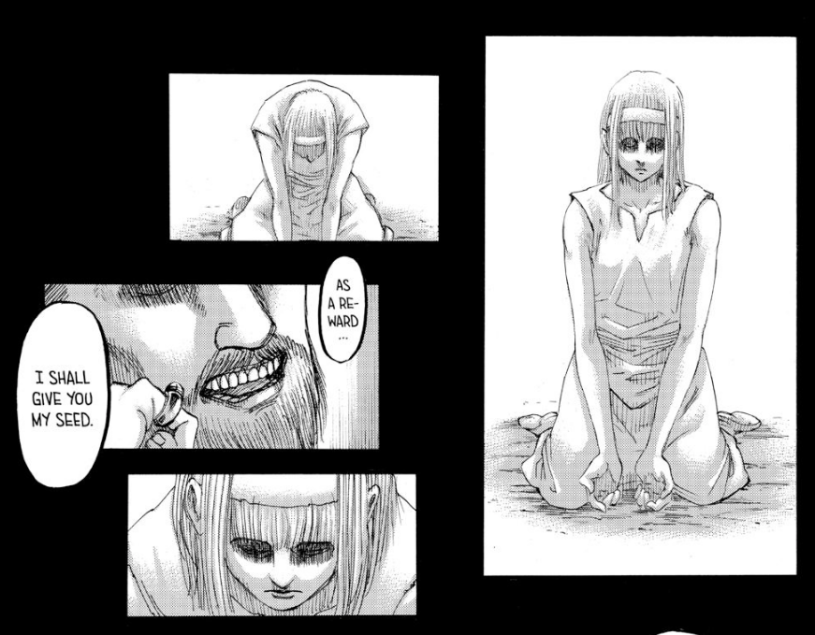

The king then decided he wanted his family to have titan powers, so he sexually abused Ymir, multiple times. The lack of consent on her end—she has no say in this matter—is made explicit. The king cut off her tongue, so it’s not like she could speak anyway.

She’s forced to bear three of the king’s children, and then dies defending him.

The king does not give a shit, as you can see, and he forces his children to eat Ymir’s body to inherit their powers (in a scene I won’t show, because it’s too gruesome for my tastes).

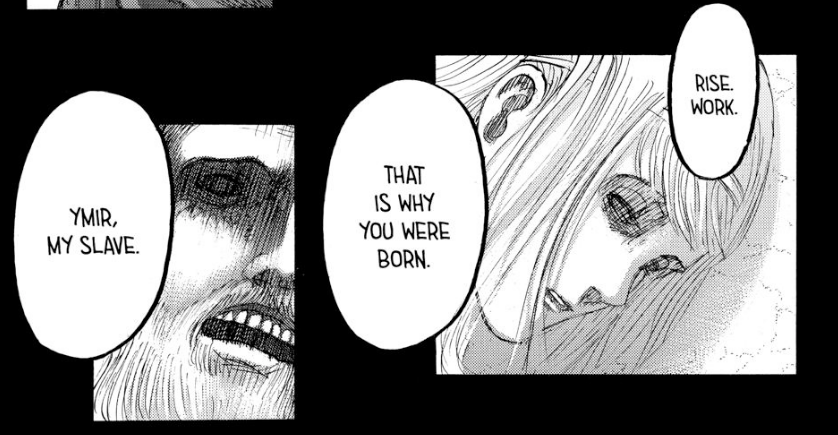

Through all this, there’s the ongoing question—why did Ymir do any of this. She could turn into a titan and kill the king whenever, we’re told multiple times she wanted to be free, she’s clearly miserable through it all. So why did she obey? Is it something related to the titans, some kind of supernatural bond? Some kind of supernatural curse?

Nah.

Ymir, the Founder, was in love with the man who’d been raping her every night since she was thirteen years old.

Attack on Titan is misogynistic even by anime standards. I told you.

So now let’s talk about the racism.

7. The Racism

When I say that Attack on Titan is a racist allegory, I’m actually talking about two completely different, independent issues. They are as such:

-

Attack on Titan is a show that uses race as a shorthand to justify conflict—and its main thesis is that the best way to solve a conflict is destructive violence.

-

The main characters of Attack on Titan are a Nazi allegory.

It’s important to study both issues separately, since otherwise it’s actively difficult to explore just how deeply problematic Attack on Titan can be. In other words: this series is, literally, so fucking racist, it boggles the mind.

I’ll start with the first point because most of my argumentation has already been made—I already said that the main thesis of Attack on Titan is that “violence is necessary”. When conflict arises between people, the only true way to fix it is by killing your enemy; this is said multiple times out loud, and the narrative consistently proves that the characters saying this are in the right.

This, eventually, reaches its logical conclusion in our main character, Eren Jaeger, committing mass genocide, and killing eighty percent of the population.

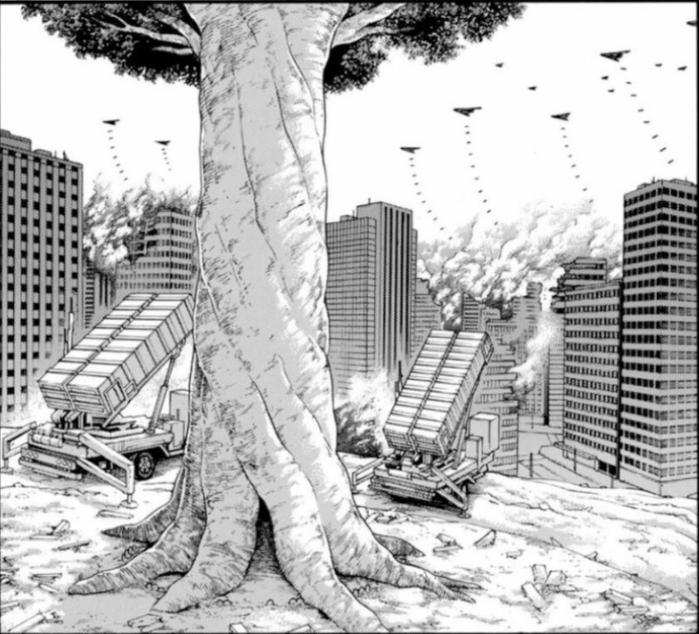

Which ironically proves not to be good enough. Since only eighty percent of the population was killed, the rest of the world eventually recovers, and carpet-bombs Eren’s hometown. He didn’t go far enough, and so, what he always feared would happen, happened:

Which means that, when he said that it was us versus them, he was unequivocally right. Violence was the solution; everything else fails.

Only, of course, Attack on Titan chooses to represent the abstract idea of human conflict through racial relations—as in, every conflict in the series is caused by race. There are no ideological, political, moral, philosophical, or even religious differences at play; war is fought exclusively because one race hates the other too much to withstand their mere existence.

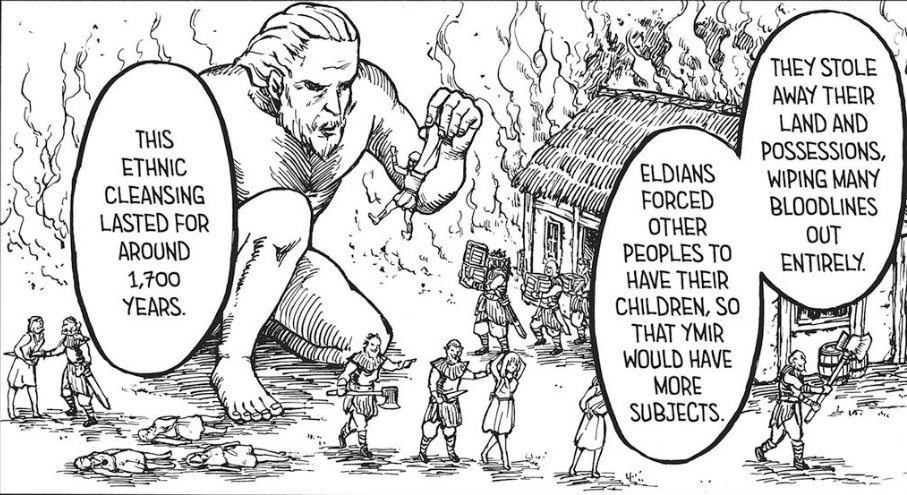

Our main cast comes from the island of Paradis. The second paradigm shift of Attack on Titan, if you remember, was the twist that titans weren’t the true enemy; it was humans. And to give you a sense of scale, here: we’re introduced to the concept of human racism when an Eldian child commits a minor offense—and as punishment, humans beat him up, and his little sister is eaten alive by dogs.

The people from Paradis are known as “Eldians” in the story, for the record. The term refers to both native Paradisians and also the descendants of Paradisians. This is important, because the hatred is not based on where they live, but rather, it’s explicitly racial.

I’ve been using “people from Paradis” as a shorthand for simplicity’s sake—it’s easier to keep terms consistent, and contextually up till now this distinction has not mattered. Since I’m discussing the matters of race now, though, it’s better to be more accurate. Attack on Titan has a specific term to designate those people who aren’t Eldians—they’re called Marleyans—but I’ll use “humans” instead, since it’s more intuitive, and that’s basically what the term stands for anyway.

In other words, from now on—“Eldians” refers to our main cast, including Eren. “Human” refers to everyone else. Eren, an Eldian, commits genocide on the human race, kills eighty percent of humanity. Cool? Cool. On with the discussion.

The explanation for such disproportionate hatred is that, in the past, Eldians tortured and killed humans for no reason. And in the present, humans do the same to Eldians. On a fundamental level, then, humans and Eldians cannot coexist. The urge to kill, humiliate, and dominate the other is innate to both races; it’s the first thing they do as soon as they’ve got the chance. Only among their own kin can they live in peace.

Which means that Attack on Titan advocates for the existence of ethnostates.

This is an inevitable conclusion, really. The story’s entire point is that violence is necessary and that conflict can only be solved when you completely decimate your enemy. At the same time, though, “conflict” is shown exclusively as a matter of race—and racism is unconditional, and cannot be fixed at a societal level. Attack on Titan advocates for violence against those who are not part of your race; there’s no other reading to the text, that’s the moral of the story.

Some characters are shown as getting over their deep-seated racism for Eldians; tellingly, these characters aren’t humans. They’re Eldians who’ve been raised among humans, treated like subhuman garbage and taught to hate their own race—and then learn that they’re not inherently inferior.

An argument I’ve been seeing says that Attack on Titan does justify the racism and the genocide within the series, because objectively speaking, an Eldian can turn into a titan at any point. They are more dangerous to the world than a simple human. All it takes is one deranged Eldian to commit genocide—and this is, indeed, what happens.

The argument then concludes that, since this is not the case in the real world, Attack on Titan is only advocating for genocide in the world of Attack on Titan, and not defending the use of genocide in abstract. As such, nobody should arrive to the conclusion that genocide is good, and if they do, they’re delusional; the circumstances of Attack on Titan simply don’t apply to our society.

As I said, I disagree with this argument. I summarize my reply in three points:

-

In-universe justifications for harmful messages in a series are ultimately meaningless. In the fiction of the show, yes, racism is justified—but the fiction is created by the author. The racism is not a natural consequence of a creative work, but rather, it’s the entire reason the creative work exists in the first place. Folding Ideas dubbed this phenomenon “The Thermian Argument”, and he explains this point better than I could. Check the video, it’s not even five minutes long.

-

Every racist person out there believes their racism is based on objective facts. If Attack on Titan is constructed in such a way that the reader comes out thinking that, well, the racists have a point in this case—then you’re opening the door to the belief that sometimes racism is justified. Attack on Titan doesn’t differentiate between the real world and the fictional world; it simply points at a situation, and says “racism is correct”.

-

The argument that the racism in Attack on Titan doesn’t parallel the racism of the real world doesn’t hold water. The racism against Eldians is based on the idea that they’re an inherently dangerous race, and such racism is a form of self-defense—this is an incredibly common speaking point in the rhetoric of racist arguments. It, indeed, isn’t true in real life, but that doesn’t mean people don’t believe it, especially if they’re already inclined to do so. Presenting this racial danger as an objective fact within the fiction is a way to legitimize the argument.

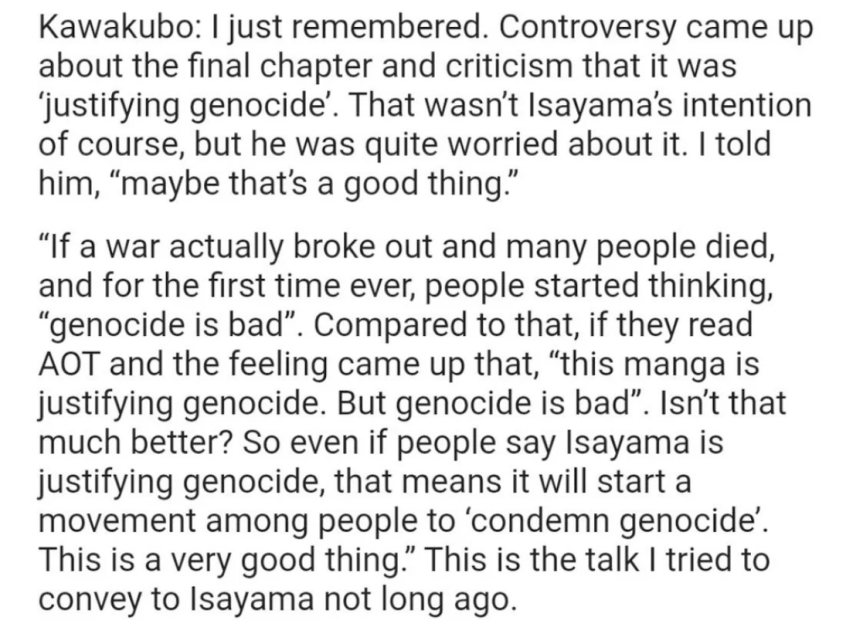

And you don’t have to take my word for it, either! Here’s the fucking editor of Attack on Titan recognizing that the series glorifies and justifies genocide in the post-finale interview!

So Attack on Titan has some pretty heavy xenophobic undertones already, only these aren’t undertones, this is more like the show’s main leitmotif. It’s repugnant. It’s morally reprehensible.

And then there’s the Nazi thing.

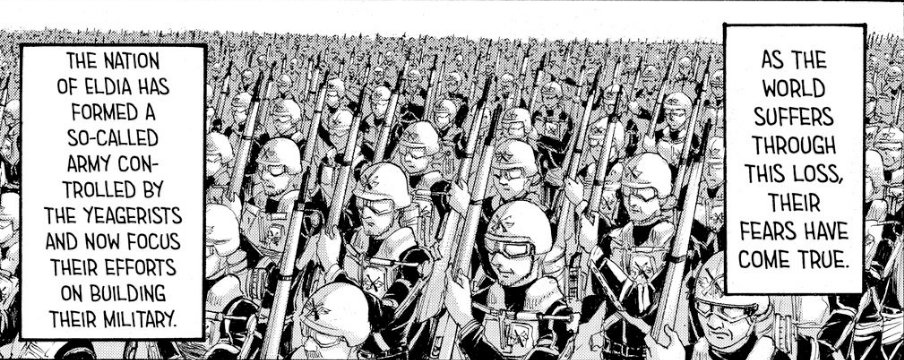

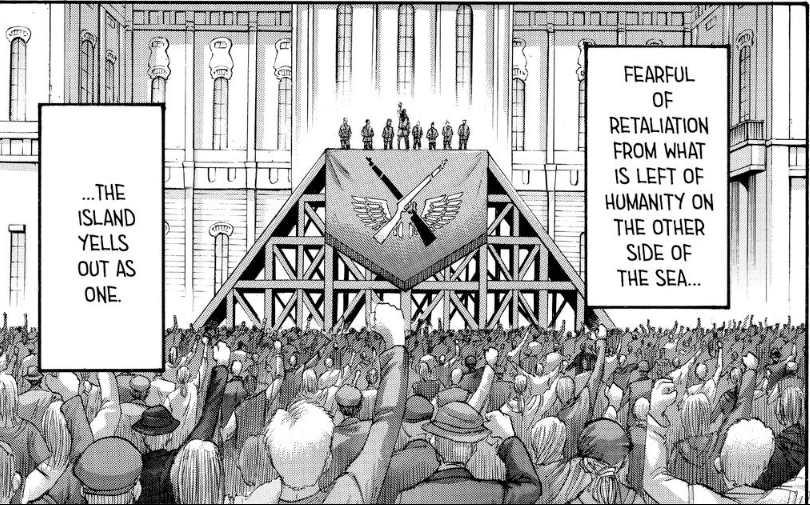

I don’t have enough time to dwell on it too much, but Attack on Titan absolutely does have fascist overtones. The glorification of the military is strong from the very start—every member of the main cast is a soldier, they join the military when they’re twelve— but it only gets worse as time goes on. The series constantly advocates for military rule; the characters organize an actual military coup d’etat where their generals take over the government and change the head of state—and this is seen as a good thing. Civilians are like cattle, doing whatever they’re told, never really taken into account. Every major decision in the story is made by military leaders, and sacrificing their own men for the sake of whatever the leaders want to do is seen as the correct, glorious thing to do.

Mind, though, that when I say “Nazi” I don’t mean it in a hyperbolic way. It’s not a shorthand for “fascist” either — I mean, quite literally, the Nazi party that terrorized and ruled Germany from 1933 to 1945. And, surprisingly, I’m not basing my argument on the fact that the series ends with a racially motivated genocide.

What I mean here is that Eldians, our main cast, read like an allegory for the Nazi regime. The further the story goes, the more obvious this becomes, the more little details start adding up to support that analysis—and quite honestly, the story doesn’t shy away from these comparisons. The imagery Attack on Titan uses is very… Y’know.

See if you spot any parallels: the Eldians started a World War in the past, and tried to take over the world. More specifically, they annexed most territories around them, to create what they called the Great Eldian Empire; in the present, Eldian loyalist want to bring forth the New Great Eldian Empire, and take back what’s theirs.

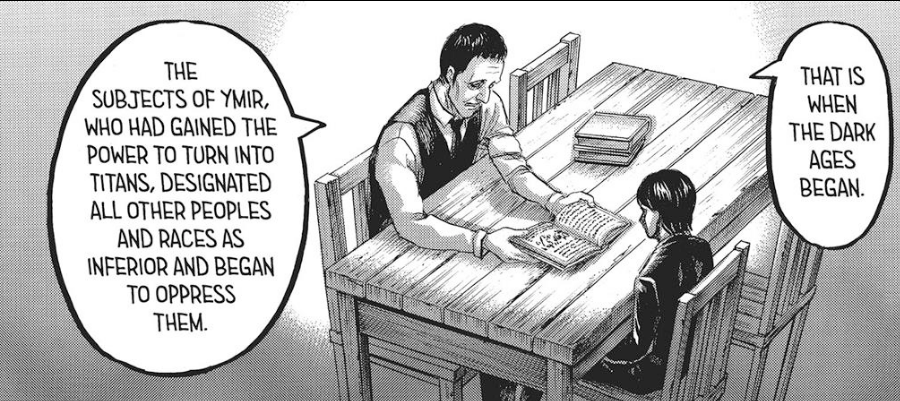

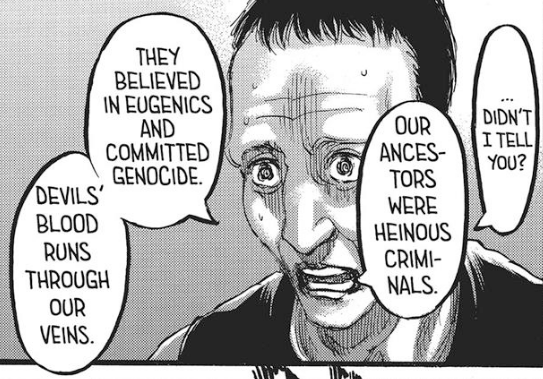

This great empire was founded on racial superiority—Eldians have the power to use and turn into titans; humans cannot. Humans were deemed inferior. They were slaughtered, oppressed, defiled, and entire cultures were eradicated.

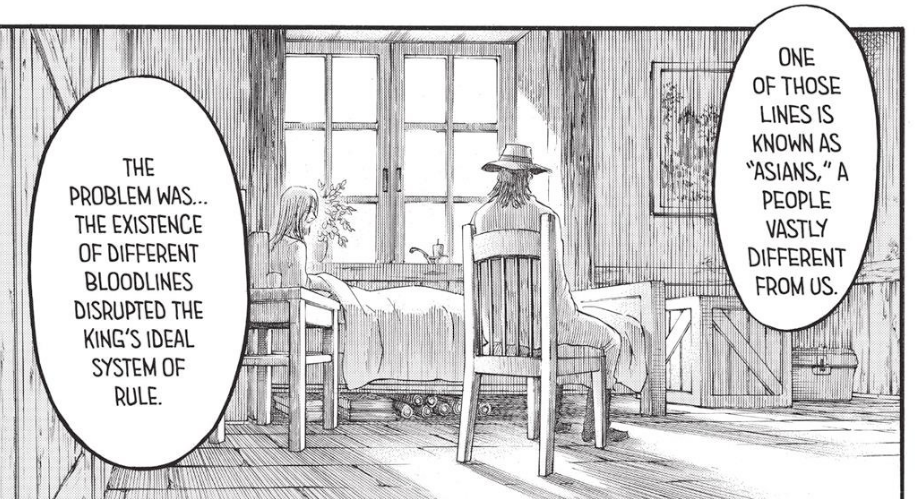

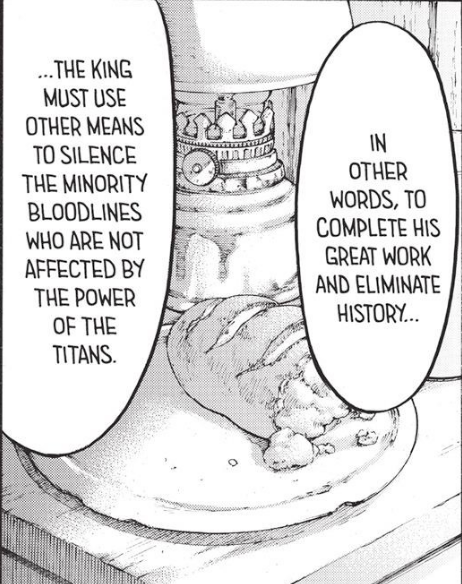

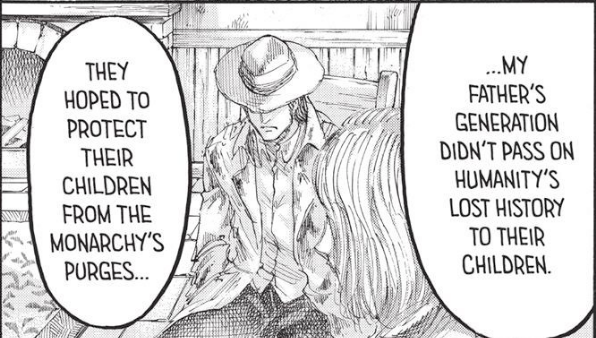

So, that’s the Third Reich. That entire bit to me read like the Third Reich, the Nazi regime. But don’t worry, just in case you think I’m reading too much into it—here’s the Great Eldian Empire’s general policy on Internal Affairs:

The Eldians ultimately lost. Their leader, Karl Fritz, grew tired of the fight and betrayed them, forcing his own people to retreat to the island of Paradis.

If you remember correctly, Paradis is the Attack on Titan equivalent of Madagascar. When I brought this up to two German friends of mine, they rightfully flipped the fuck out, and linked me to this page. I told you that the picture of Eren as King Julian would be relevant. I told you.

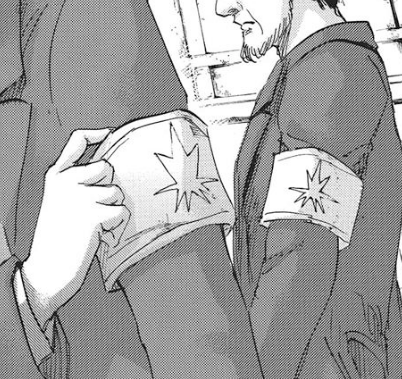

Not every Eldian was brought to Paradis, though. Some others were kept outside—and their descendants are the victims of the heinous racism I described above. Humans call it justice, because they’re doing to the Eldians what the Eldians did to them. And of course, this includes marking them with yellow stars, and red armbands:

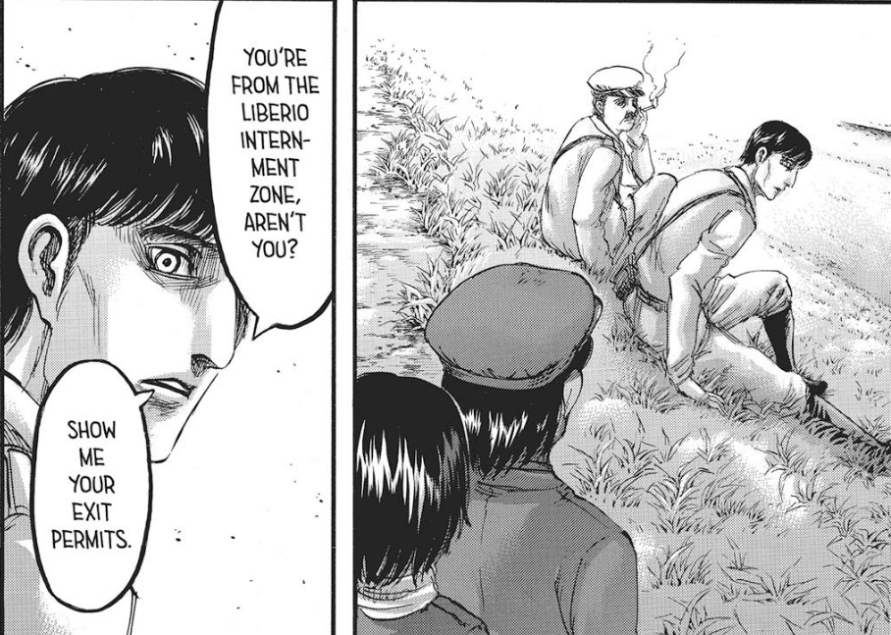

They’re forced to live in ghettos, and can’t leave without a special permit:

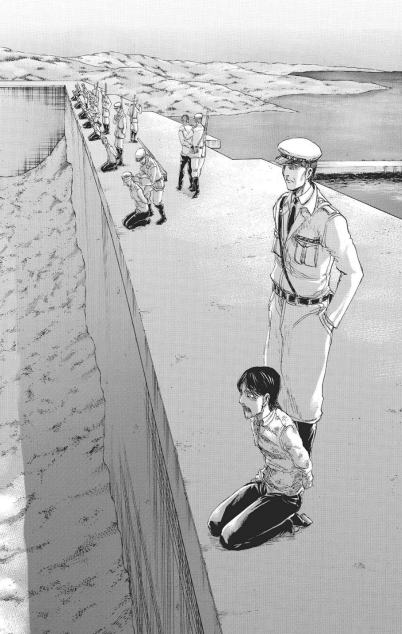

And they’re executed en masse, in a way that looks like this:

Some Eldians rebel against this. They become restorationists—carve crosses in their own bodies as a sign of their loyalty to the cause. They’re not swastikas! They’re just crosses. Phew.

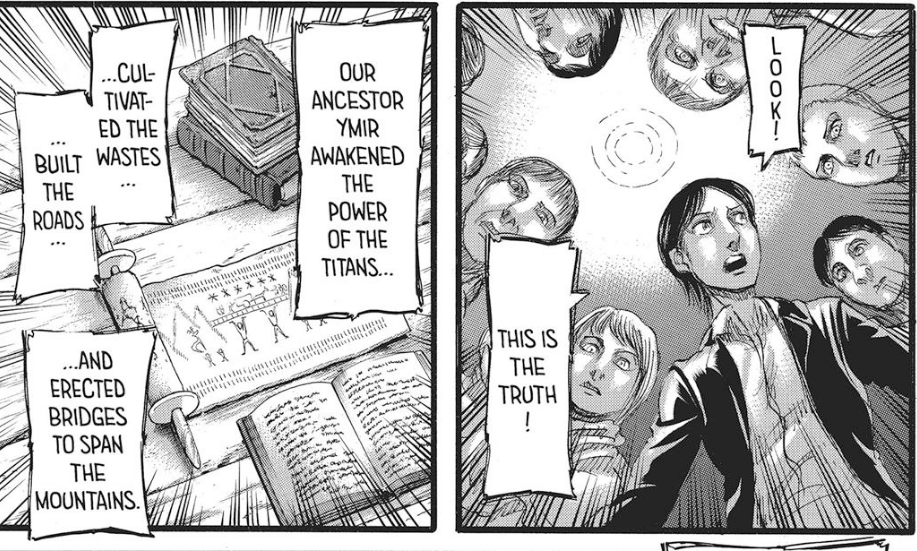

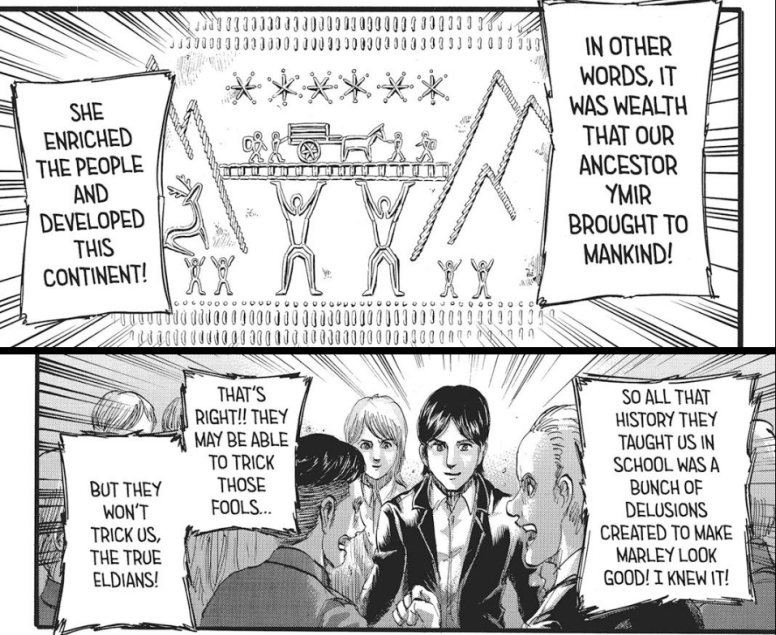

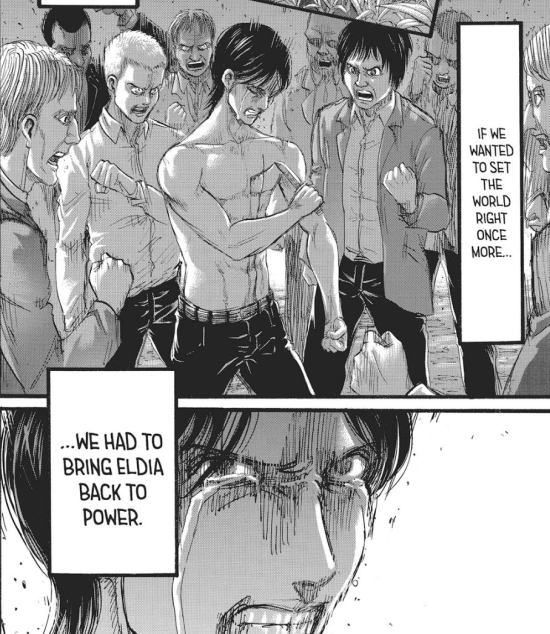

The restorationists also believe that the Great Eldian Empire horror stories are propaganda, and that their ancestors actually mostly did good things for the people they oppressed. Like, sure, they raped and killed and pillaged everything in sight—but they also built trains!

Back in Paradis, the people loyal to Eeren Jaeger create a group called the Jaegerists—or Yaegerists, depending on which translation of Eren’s last name you choose—a group of nationalist, warmongering alt-righters, who want to kill everybody else, and protect the future of the new Eldian Empire.

By the end of the series, they’ve taken over Paradis, and are building an army to, I guess, continue the war against the rest of the world.

And of course, there’s, yknow. The fact that it all ends with Eldians committing a mass genocide on humans.

I’ve seen people argue that Eldians aren’t a Nazi allegory, but rather, that they’re an allegory for Jewish people. It’s humans who represent the Nazis. This is because in the current time of the series, it’s Eldians who are forced to live in ghettos, it’s Eldians who are oppressed.

I don’t agree with this reading, though, because that implies ignoring everything else regarding Eldian history. To me, the Jewish parallel isn’t there; Eldians are, indeed, currently oppressed—but this feels less like a callback to the horrible persecution Jewish people have suffered through history, and more a representation of modern blowback against, uh. Nazis, I guess. I also feel the need to add that Eldians being an allegory for Jewish people would, if anything, be worse. Eldians turn into horrible, often big-nosed monsters who feast on human flesh, and openly recognize they used to rule the world. In a way, it makes the series feel more explicitly anti-Semitic.

It’s a testament to the ambiguity of allegories that the main division among literary analysts of this story is who, exactly, are the real Nazis. In my defense, I’ll also add that the article linked above was written before Eren committed genocide; that little fact does tip the scales somewhat.

So, yes. My reading of Attack on Titan is that, whether on purpose or accidentally, the story functions as a commentary on the hardships of being a Nazi in the current climate, a la “we’re the oppressed ones, actually”. Political correctness gone mad sorta deal.

Hell of a fucking thing to complain about. I suppose saying “authoritarian right-wing nationalist” instead of “Nazi” would cast a wider net and make that statement less controversial, but the story uses such explicit Nazi imagery that I don’t want to use vague language. It feels dishonest on my end.

Does this mean I think the author is actually sympathetic to the Third Reich? Am I accusing Attack on Titan of being Nazi propaganda? Yes and no. I don’t know to which degree all the parallels I see are intentional, and which are simply me seeking patterns where there are none. It’s entirely possible—and very likely—that some of the things that make me arch an eyebrow are entirely unintentional, and simple coincidences.

However.

I do not think, in the slightest, that everything I just mentioned is a coincidence. Neither do I think my reading is me adding meaning to the story when there’s none. Attack on Titan is an intended commentary on the author’s distaste for people’s unwillingness to look past atrocities or crimes against humanity when examining historical events or figures. “Can’t we just focus on how much the Nazis did for medicine, instead of the Holocaust—in the end it was almost a net positive” sorta thing.

Three pieces of evidence for this reasoning:

1. The characters tells us we should look at the silver lining of past atrocities

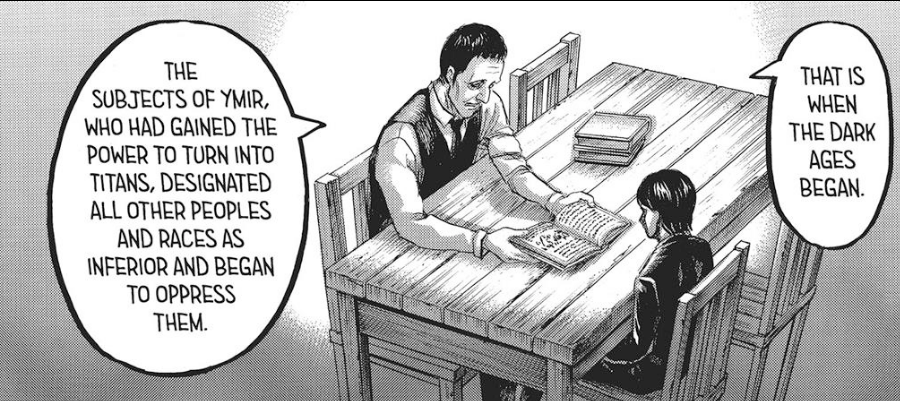

If you remember, we’re told of the Eldian/human conflict when a kid’s little sister is eaten alive by dogs. This conversation happens right after we’re explicitly shown the Eldian Empire was the Third Reich:

In-universe, yeah, no, the kid is absolutely right. His little sister got viciously murdered, and he got beaten up, for no reason. “Your ancestors were devils” is just racism with a couple extra words. He suffered a heinous hate crime, and it’s impossible not to side with him in this scene.

In a meta sense, though, what with the whole Nazi parallel, this scene gets a little bit trickier, though. Eldians are a race—is the story saying Germans in particular are oppressed? Or are Eldians a parallel to people who hold beliefs similar to Nazism, and this is complaining about the “unfairness” of considering fascism inherently heinous for what Nazis did in the past?

Later, the same kid who argued that he hadn’t done anything grew up to be the guy defending the old Eldian Empire, and the leader of the restorationists. He’s the one who says this:

So, yeah, we didn’t commit any genocide—and either way, was it really that bad? Look, we did a lot of good, too. There’s shades of grey to it all, etc etc. Furthering this narrative are the next two points.

2. Commander Pixis is based on a war criminal

Remember the guy who wanted to be vored by a hot titan lady? His name is Commander Pixis, he’s a prominent, important, noble figure in Attack on Titan, and the author directly recognized basing the guy on Akiyama Yoshifuru, the father of modern Japanese cavalry, and massive war criminal. Source. English article talking about it.

This admission caused a flame war—Akiyama Yoshifuru was a prominent figure in the First Sinto-Japanese war, and comments were made on his participation on the either by actively joining in, or by passively letting it happen.

The Port Arthur Massacre of 1894 (not to be confused with the Australian tragedy of 1996) is in itself controversial—first reported by a Canadian journalist as an unimaginable act of cruelty against civilians on account of the Japanese army, independent investigators sent by the US State Department concluded that most of that reporting had been exaggerated.

The massacre itself is not debated—we know it happened, that’s a fact—but the exact scope of the tragedy is unknown. Accounts vary from as much as 60,000 dead to as “little” as 120 civilians, and an unspecified amount of soldiers. The Japanese Foreign Minister Mutsu Munemitsu argued that only soldiers dressed as civilians had been killed; his inquiry resulted in no punishments towards the troops. To quote directly from the Wikipedia article:

The Japanese press generally avoided reporting on the massacre, or dismissed it, as when the Jiyū Shinbun called allegations “an invidious desire to detract from the glory of the Japanese Army”. The Shin Chōya accused Westerners of exaggerating the extent of the atrocities, and of hypocrisy in light of the atrocities they had committed throughout the East, stating that “the history of savage nations that have come in contact with Christian Occidentals is all but written in blood”. Some questioned Creelman’s reliability, and a rumour spread that he left for Shanghai after the fall of Port Arthur to work for the Chinese government. The Japan Weekly Mail, on the other hand, castigated the Japanese army in several articles. Attempts to launch an inquiry met resistance from those who wanted it covered up. The inquiry resulted in no punishments given out.

The Port Arthur Massacre is just one example—but it’s representative of the kind of figure that is Akiyama Yoshifuru. Within the context of a story that already deals with characters denying the relevance or verisimilitude of past atrocities (and I need to emphasize that the people saying that are, explicitly, Eldian restorationists, they want to bring back the Great Eldian Empire), and which already justifies the usage of violence against members of any other race, it’s…

It’s not a good look. Quite frankly, while from a Eurocentric perspective we immediately draw parallels to the Nazi regime—intended parallels at that; I’ve already shown enough evidence—from a more Asian point of view, this gives the vibe that the author of Attack on Titan might be, y’know. A Japanese imperialist?

Which drives us to my third point.

3. There’s a lot of evidence that the author of Attack on Titan may be a Japanese imperialist.

Who could’ve seen that coming.

Japan has infamously glossed over past atrocities committed against China and Korea in their history textbooks and in their general educational system. These accounts go from the denial of the existence of “Comfort Women”—the name given to refer to the victims and survivors of Japan’s brutal sex slave trade, which ran from 1932 to 1945 in multiple occupied Asian countries, but especially Korea and China to the still very present, still very real denial that the Nanjing Massacre (also known as the Rape of Nanjing) ever happened.

This adds much-needed context to the points I was raising earlier: if a Japanese manga keeps hinting at the idea that the history of past atrocities has been exaggerated or overstated, that in truth they brought good to the world by colonizing other countries, and those who say otherwise are simply lying—that’s a massive red flag. It’s, in essence, a dog whistle.

And then people found the author’s private Twitter account. To quote directly:

The @migiteorerno account is private, but some tweets are visible on the site Favstar that organizes tweets by number of times favorited and retweeted.

One that has been spread across South Korean news articles to various blog posts apparently reads “I believe that categorizing the Japanese soldiers who were in Korea before Korea was a country(??) as ‘Nazis’ is quite crude. Also, I do not believe that the people whose populations were increased twofold by Japan’s unification(??) of the country can be compared to people who experienced the Holocaust. This type of miscategorization is the source of misunderstanding and discrimination.”

@migiteorerno dismisses how Japan’s imperialist war atrocities are often considered the East Asia equivalent to the Holocaust, instead giving credit for Korean’s modernization to Japan’s colonization.

Interesting to note that the Holocaust comparisons aren’t purely due to a Eurocentric reading of the series either—as I mentioned, the visual parallels are definitely intentional—and from what I understand, it’s not like comparing a denial of the Holocaust with a denial of Japanese war crimes is a new thing either way.

As a side note, this does suggest the alternate reading that Eldians stand, not for the Third Reich, but rather for the Empire of Japan. In exchange, the humans do stand for the Nazi regime, and the point of Attack on Titan is now “look how much worse they are” by having the Nazi humans opress the Eldians.

Ultimately, this changes very little of my criticism towards the series, since it’s still justifying genocide and criticising the perceived overstatement of past atrocities. You just change the exact flavor of genocide you’re defending.

While the @migiteorerno account has never been officially linked to the author of Attack on Titan —whose name is Hajime Isayama, in case you forgot— there’s enough evidence for most people to assume it is actually him. Here’s a skeptic being convinced by stuff like @migiteorerno tweeting about the movie Elysium immediately before Isayama talks about it in his official blog. Here’s someone pointing out how @migiteorerno apparently keeps contact with a lot of Isayama’s associates, editor and assistants included.

My source above—the one where I took the translations of the tweet from—expresses, if not outright disbelief, at least a little bit of despair at the possibility of @migiteorerno being Isayama’s account. The reasoning is, according to the writer, Attack on Titan runs a message that’s opposite to that of Japanese imperialism: the military isn’t glorified, war is horrible, and oppression is inhuman.

And once again, I get it. While Attack on Titan was running, it was difficult to know where the story was leading. The ending is fundamental to understand the thesis of a story, and Attack on Titan in particular doesn’t really do “thematic arcs”. Everything is in service to the main thesis.

The ending, however, revealed that the thesis is, as I already argued, that violence is necessary, and the only way to solve conflict. The focus on race as a way to represent the abstract idea of conflict makes the story feel racist by itself already—but the more you look into it, the more you analyze the storyline, the worse it gets.

I’ll be quite frank: even if we’re being charitable, even if we assume all these parallels were unintentional, a complete coincidence, it doesn’t excuse it. When a certain reading of a work is common enough to be perceived so universally, it does not matter whether the author intended it, because the reader doesn’t see the intent behind a work of art. The reader sees the work itself.

And some of these are, I must insist, absolutely intentional. Mikasa, Eren’s half-sister who does nothing, is reportedly named after the battleship Mikasa, which, wouldn’t you know, fought in the Battle of Port Arthur in 1904. Like, I mean, come the fuck on.

“Unfortunate implications” is a couple of words that I see thrown around a lot when talking about these topics, but in the year 2021, this is not “unfortunate”, this is negligent.

Here’s an article on how the alt-right fucking loves Attack on Titan.Here’s the kind of memes I kept seeing whenever I browsed around Attack on Titan subreddits. Here’s some of the reactions to the joke. Here’s some more.

Genuinely, from the bottom of my heart:

Fuck this series.

And fuck what it stands for.

8. The Conclusion

At the start of this blog series, I called Attack on Titan a bad series. From a purely technical point of view, I was accurate—I think Attack on Titan completely destroys its own sense of escalation, it sacrifices its characters in the name of its thesis, and the ending is both too abrupt and too slow to make any sense. Characters are dropped mid-series, subplots are forgotten, foreshadowing leads nowhere.

But from a philosophical point of view, Attack on Titan is not just bad, it’s despicable. By itself, the thesis about violence would be bad. By itself, the Holocaust/Japanese imperialism allegory would be repugnant. By itself, the glorification of genocide and advocacy for an ethnostate would be abhorrent.

And we get all three of them, at the same time.

That’s why I decided I wanted to review Attack on Titan. I started this series back when it first came out in 2009 and quickly dropped; pop cultural osmosis was enough for me to somewhat keep up with the storyline. Then the in-universe genocide happened, and the ending happened, and that’s when I actually went back to the start of the series and re-read it all in one go.

I don’t recommend Attack on Titan. Lurking around fan spaces has taught me that people get really into joking about the genocide—and many end up complaining that the series didn’t go far enough, that they should have killed more people.

I don’t think that’s a coincidence, and I don’t think that’s simply people being edgy. Within the story’s universe, it makes a grim sort of sense to advocate for a greater genocide—that’s the true evil of Attack on Titan. In-universe, it justifies itself.

But it’s the author who writes those justifications. The genocide doesn’t happen as a “natural” consequence of the circumstances that lead to it. Those circumstances were put there so that a genocide could happen.

Attack on Titan presents a warped view on humanity so that the political and philosophical stance of “violence is necessary, and atrocities shouldn’t be dwelled on” can hold any water whatsoever. And I just can’t ever recommend that, or call it anything but, at best, horrible. At worst, evil.

The micro writing of Attack on Titan is engaging; that makes it worse. That makes it not only propaganda, but effective propaganda. Every story is, in the end, a way to convey a certain message, a certain moral. And it’s important, when consuming media, to understand what the story is telling us, and what the author is trying to sell.

Because otherwise, we run the risk of buying it.

About Aragon

Spanish author, cartoonist, legal scholar.