Let There Be Light

by Wholesome Rage | 28 March 2018

John Huston directed a movie in 1946 that was so subversive, so radical, that it was suppressed by the US army until 1981

You might not recognize John Huston by name, but you know some of his other works; From “The Maltese Falcon” in 1941, to “The Man who Would Be King” in 1975. You might not have heard of “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” starring Humphrey Bogart in 1948 — but it was a movie that Stanley Kubric would list as his fourth favourite, and Sam Raimi as his all time first.

In 1950 he wrote and directed The Asphalt Jungle, one of the first movies to portray criminals as sympathetic characters… and the movie that made Marilyn Monroe.

He followed with 1951’s Red Badge of Courage, and this is the one I want to dwell on first. In fact, forgive me if I continue to throw a few more plates into the air, and we’ll catch them with a title drop later.

The Red Badge of Courage casts as its leading actor Audie Murphy, a very talented young man. In 1949 the financial backers of the movie Bad Boy had refused to finance it unless this young man could get his first leading roll in it, twisting the studio’s arm into taking the risk on him. He’d marry the actress Wanda Hendrix at the end of 1949, but they’d be divorced by the end of Red Bade of Courage’s shooting year. Together they’d starred in Sierra, and Murphy proved himself perfect to play the bad-boy of the cowboy movie era…

All this is Hollywood history, but it’s Hollywood history of the 1950’s, which means it’s not the history I plan to be looking at. In fact, all this time, I haven’t really been talking about Hollywood history. What I have been talking about are the war heroes who would bring awareness of post traumatic stress disorder to the public eye, and force the public to be aware of the difficulties its soldiers faced in peace time.

This isn’t just about director John Huston and actor Audie Murphy. It’s about Major John Huston and Lieutenant Audie Murphy.

This is about the invisible wounds, about how something very important to these men got damaged, in a time when you couldn’t admit that. When psychological damage was seen as very different to how it is today. When the army just dubbed it ‘shellshock’ or ‘battle fatigue’.

Here’s a charming quote from Quartered Safe Out Here, a first person account told by George MacDonald Fraser of his experience as a soldier in Burma during WWII

It was a reminder that I had not been trained for authority in eccentric warfare. The young soldiers’ battalion had given excellent military instruction, but no guidance on […] how to cope with a seasoned veteran who, in a lonely basha at night, swore that there were Japanese outside, hundreds of them but only eighteen inches tall, and led by his Member of Parliament, Sir Walter Womersley, Minister of Pensions. He was the only case (the veteran, not Womersley) that I ever encountered of what is now called, I believe, post-battle trauma; I’m sure it would need psychiatric reports and counselling by social workers nowadays, but the section simply advised him to take his kukri to them – which he did, cleaving the air and crying: “Pensions, you old bastard!” before going back to sleep. He was entirely normal for the rest of the campaign.

This account was written nearly fifty years on, and you can see some of the disdain for psychiatric help of the time period leaking through. Psychiatry was a fairly new profession, too, it should be said; The psychiatric admissions test of WWII was a fairly interesting gauntlet to run, and would deem Richard Feynman as a raving lunatic… for entirely the wrong reasons! That’s missing the broad side of a barn and shooting yourself in the foot right there.

Regardless. From a combination of public disdain, government fear of acknowledging a growing problem of veteran care, and psychiatry being too… well, young as a medical profession to truly stand up to these outside forces, soldiers with PTSD were feeling more and more alienated from the society they returned from.

Audie Murphy fought this, like he fought so many things. He is the single most decorated US soldier to ever serve who, despite all the movies he starred, despite his close work with John Huston, has this as the first paragraph on his Wikipedia page:

Audie Leon Murphy (20 June 1925 – 28 May 1971) was one of the most decorated American combat soldiers of World War II, receiving every military combat award for valor available from the U.S. Army, as well as French and Belgian awards for heroism. Murphy received the Medal of Honor for valor demonstrated at the age of 19 for single-handedly holding off an entire company of German soldiers for an hour at the Colmar Pocket in France in January 1945, then leading a successful counterattack while wounded and out of ammunition.

How does Wikipedia describe that event?

The Germans scored a direct hit on an M10 tank destroyer, setting it alight, forcing the crew to abandon it. Murphy ordered his men to retreat to positions in the woods, remaining alone at his post, shooting his M1 carbine and directing artillery fire via his field radio while the Germans aimed fire directly at his position. Murphy mounted the abandoned, burning tank destroyer and began firing its .50 caliber machine gun at the advancing Germans, killing a squad crawling through a ditch towards him. For an hour, Murphy stood on the flaming tank destroyer returning German fire from foot soldiers and advancing tanks, killing or wounding 50 Germans. He sustained a leg wound during his stand, and stopped only after he ran out of ammunition. Murphy rejoined his men, disregarding his own injury, and led them back to repel the Germans. He insisted on remaining with his men while his wounds were treated.

Audie Murphy is one of the most indescribable human beings of all time.

So why do I bring up his work with John Huston, then, with Red Badge of Courage, and not To Hell and Back, made in 1955? To Hell and Back was, after all, made from his memoirs, and Red Badge of Courage was a commercial flop.

Here’s where we start catching all these plates.

To Hell and Back was a huge commercial and critical success, but Murphy had wanted to use it as leverage to get the movie he really wanted made, The Way Back, about dealing with PTSD. He could never get finance for it.

Murphy was addicted to anti-insomnia drugs for his nightmares. He couldn’t sleep without a loaded pistol under his pillow, and Wanda Hendrix would describe him pulling guns on her over disagreements. He would fight hard, during Korea, to expand government healthcare afforded to Veterans to include considerations of the psychological and emotional damages of combat experiences.

Not even the most decorated war hero of the 20th century, and a cinema legend in his own right, could pull off making a movie about it though, and bringing it to the public on his own terms.

John Huston had tried to make that movie with him first, in 1951 with Red Badge of Courage. But MGM had seen the message of that movie as too antiwar: They cut the film from eighty-eight minutes to sixty-nine, added narration, and deleted an important scene, because Huston had said it “brought war very close to home.”

All this, all this is just to emphasize the significance with which Let There Be Light was made. Made in 1946 with a runtime of just under an hour, it is an unflinching, heartbreaking look at veterans of the war recovering in a psychiatric hospital.

This movie had no legendary actors backing it. The war heroes it showed were not named. There was no script. It was as scathingly anti-war as you could get at the time.

Major John Huston of the US Army Signal Corps. got it made. I cannot stress enough just how colossal an undertaking this must have been to not have had this footage outright destroyed. That we have it now, so well preserved, is a miracle. It was suppressed until well 1981, in a condition so poor you couldn’t really understand what was being said. The edition I watch now is the restored version released in 2012, now released to the public domain.

About 20% of all battle casualties in the American Army war during World War 2 were of a neuropsychiatric nature.

This is the opening splash of the 1946 movie Let There Be Light. It continues with this;

No scenes were staged. The cameras merely recorded what took place in an Army hospital.

Then the narration kicks in. Peace has come, the seas of the Earth are filled with ships of men coming home. A shot of nurses carrying stretchers.

Here is human salvage.

The calm radio voice of the 40’s intones this with such solemnity. Before my heart can catch up to what that pair of words, it follows;

The final result of all that metal and fire can do to violate mortal flesh. Some wear the badges of their pain. The crutches. The bandages. The splints.

Others show no outward signs, yet they too are wounded.

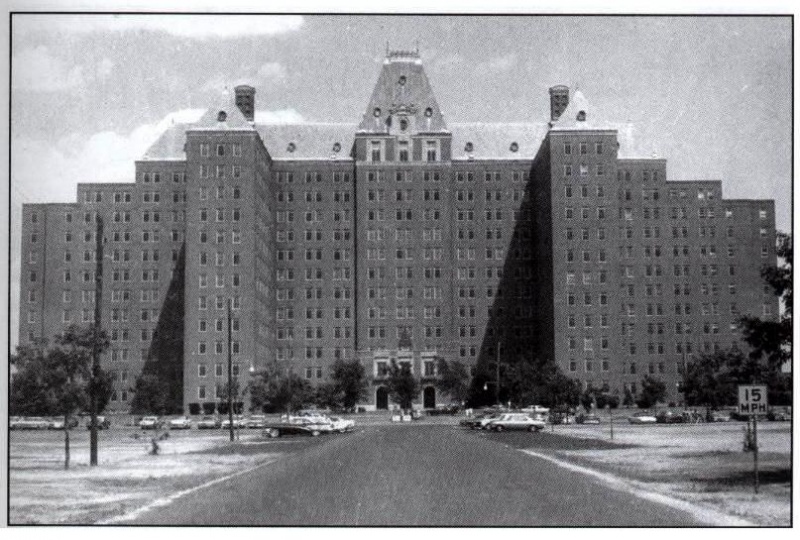

So many young, impossibly young men are taken from ships and packed into a fleet of ambulance, and are poured out into a large Army hospital.

It’s a cheerful place that in no way has inspired me to write a World Of Darkness: Asylum campaign right now.

These are the casualties of the spirit.

Every man has his breaking point.

And these are the men, who in fulfillment of their duty as soldiers, were pushed beyond the limits of human endurance.

I think it’s worth remembering, and highlighting… how normal these people look. After years in the killing fields of France and Germany, on the Pacific islands against the Japanese, these men and watched friends die. And here they sit. A lot of them are pretty handsome, actually, but they mostly look bored and anxious by the introduction lecture they’re sitting through, telling them not to mind the cameras.

This is the image we see when we are told what a man looks like when he has been pushed past the limits of human endurance. It’s this frame.

On the other side is a man who shakes and twitches uncontrollably, far more like what you’re used to seeing to the Hollywood madman. His eyes are keen and focused on the speaker even as his head thrashes about.

But when the narration follows with the line

These are men who tremble

It’s not that man we cut to, but the man sitting next to him that looks like this

It’s a powerful statement of editing, it truly is. Your eye has naturally found the twitching fellow beside him in the previous shot; he’s the only movement in an otherwise still frame. But when the shot follows to a close up and states men who tremble, they don’t highlight him.

This is a man, it says, who is just as damaged as the visibly shaking one beside him, but the scars are more invisible.

And throughout, this narration makes one thing clear. For these men to be here, where they are now? They are absolutely worthy and deserving of your respect. They are not here because they are weak. They are not here because they weren’t strong enough. They are here because we asked something of them that no human being should possibly be asked, and they did it.

Eighty two years later and I’m struggling to think of another work that handles this kind of mental illness with such dignity and subtle brilliance.

These are men with pain that is nonetheless real even though it is of mental origin.

Despite the difference in their symptoms, these things they have in common. Unceasing fear and apprehension. A sense of impending disaster. A feeling of hopelessness and isolation.

Then we see the interviews, the psychiatrists giving one on one time with each patient and asking them to tell their story as best as they can.

Their eyes dart about as the memories play out so clearly in their minds. They’re forced into low mumbles that even the remastered edition cannot make out — I put the subtitles on.

And here I get to the reason this movie was suppressed for so long. This movie meant to help returning soldiers explain to their families why they were different, how hard it was for them. To show the seriousness of ‘battle fatigue’.

It would drive down recruitment.

The second soldier they show is a Ranger. The cameras make sure that insignia on his uniform is visible, without drawing too much attention to it. Rangers lead the way. Not even the Rangers, so surrounded by mythos of their brilliance and bravery, are immune to appearing in this film.

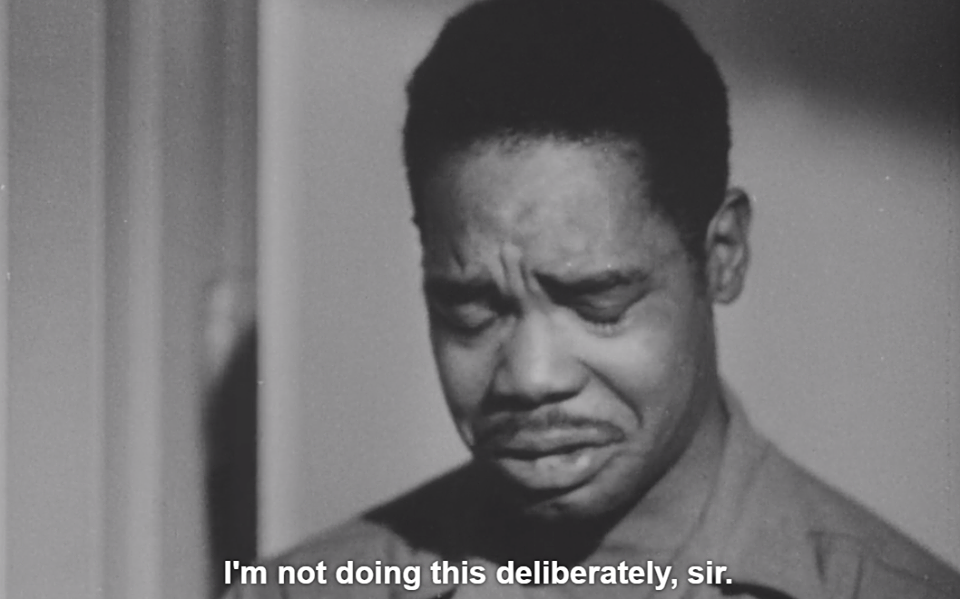

He tells the story of how he became the last survivor of the original group he was sent out with. He starts rambling, and the doctor cuts him off;

How did you feel when you got shelled?

I dunno. I guess, after Norman got hurt — killed… why, I was all right when we were moving up or attacking or anything like that, but when we got pinned down I’d think about him laying back there.

And how did it make you feel, thinking about him?

I didn’t care what happened to me.

You mean you didn’t want to go back into combat again?

No sir, I wanted to go back, and I wanted to stay there. I wanted to keep on for him, and for all them other guys; For Norm, John, and Stryker… for Tex and Pop and-

And how do you feel right now?

I feel alright.

The ranger says this staring at his shoes. His eyes haven’t gone any higher since he mentioned Norm’s name.

It’s interesting to note that when he says he was okay when he was moving up and attacking, that it was stopping that was the problem. This is something that had been known about for well over a hundred years at this point. Captain John Kincaid of Wellington’s legendary 95th rifles, the men who would prove the superiority of light infantry doctrine during the Napoleonic wars, would write passionately about the importance of psychology in warfare in breaking the tradition of line infantry; That moving forward kept a soldier’s mind focused, but the fear for their safety and awareness of their mortality would kick in again the moment they stopped and took cover. That doing nothing was the most terrifying thing a soldier could face.

The argument, then, was to keep skirmishers moving in combat to keep them able to focus on and follow orders. But here we are sitting in Mason General hospital in 1946, watching a man who has no ground left to advance, no battle left to give.

Another man stares vacantly at the wall behind the doctor’s head.

Do you feel changed? Are you aware of the feeling that you are not the boy that you felt like when you went over?

His voice drops back to barely a whisper.

Yes, sir.

In what way?

I used to like to have fun. I used to always be going places. I don’t like to do nothing no more.

Another man speaks so fast the words are practically tumbling out of his mouth, describing all the ways he used to keep himself distracted. He’s lucid and legible, but it’s contrasted and juxtaposed to the slow, quiet, deliberate way the previous man spoke. His almost-mania is a sharp contrast.

With each of these scenes of first-round interviews, favourites aren’t given. We aren’t drawn to the cinematic spectacle. Instead it’s a montage used as a palette, not only to highlight and show the pain of these men, but to show just how varied the symptoms are, and how all these men are equal in a way.

It defies any attempt to pidgeonhole or stereotype the issues it portrays. The order of the cuts and where they happen are precisely calculated to show as much contrast as possible, and let only the intensity and disability of these men shine through as their sames.

It’s such an important style of editing, with so many hours of raw footage they could have chosen from. It prevents grouping together of symptoms.

The man who stutters is contrasted to the man of serene eloquence. The man who is terrified of death and dying is contrasted to the man who can’t care anymore and longs for it.

We move on to show the treatment itself.

Each man gets to make a long distance phone call, then settles in. This place will be his home for the next eight to ten weeks of his treatment. The lights go out as they stare sleeplessly and open-eyed at their ceilings. Nurses rush to men who bolt upright in their beds in cold sweats as the shadows of the room become shapes.

They’re shown to be brave men, soldiers. The music is sad, the narration is solemn, but the men? They’re action heroes, fighting one last battle.

These scenes aren’t just here to make you pity these men. Huston is a master of the action drama; these are the insurmountable odds these men must triumph over. To keep the drama, there’s always the implication that they simply might not. In doing so — in keeping with the brutal honesty of a documentary maker combined with the keen storytelling eye of an action movie director who had spent the last four years in active warzones — he has to acknowledge this harshness, and the reality of the suffering, which is probably why this movie ended up so buried.

But it makes the documentary all the more compelling for these flourishes.

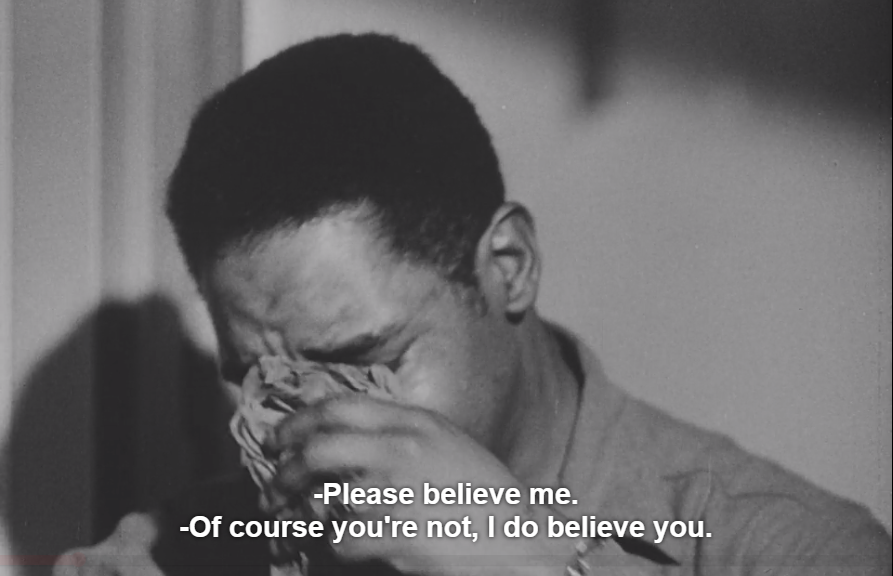

A man is carried limping down the corridor, a nurse under one arm and a friend under the other, who pass him off to a doctor. The narrator tells us that his paralysis is purely psychological, but it’s just as real as any spinal injury. Rubber hose is wrapped around the guy’s bicep, and he’s given an injection of sodium amytal, to induce a hypnotic suggestive state.

“What a torpedo that is. You mind if I look away, Doc?”

Interestingly, you might be more aware of the drug as a famous ‘truth serum’. Apparently it’s still prescribed today for acute cases of anxiety, epilepsy and insomnia.

Then… well you have a straight window into 1946 psychotherapy. The man, under a hypnosis-like state, talks to the doctor, and the doctor talks back, and it’s… indescribably surreal.

Honestly, as much as I’ve been giving a blow by blow, from here on out I have to suggest just watching yourself. Just… the archaic nature of it, combined with its results, this man gets up and walks just because he’s been told he can rather sternly, is… it’s surreal. I can see why this inspired so much science fiction, and so many authors.

And again, the narrator repeats:

This man has not been cured. That will take time.

It’s 1946. Here, Huston has footage, real footage, of such a staggering moment; a man walking out of a room he had to be dragged into. In another edit, in another cut, by another man, that footage would have been this movie. A reaffirmation that the population just needed to shake it off and get back to work.

Then there’s footage of a group therapy session. God, it’s so Freudian. It’s-

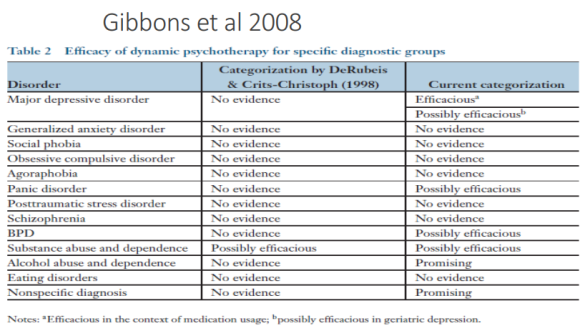

So yeah, it turns out a lot of this ends up being Freudian therapy, which hypnosis is associated with. I’m not remotely qualified to talk about, but according to someone who is, this is a fairly comprehensive summary of this therapy.

Honestly? Knowing what I do about psychotherapy, a lot of this footage made me genuinely uncomfortable. The same valiant portrayal of the patients is given to these doctors, rigid men of science and medicine fighting to help these men through some of the hardest times of their life…

… but the methods they’re using are Freudian.

God, it’s like… It’s such a juxtaposition. So much of what we know is wrong they don’t know yet. Is forgiven at the time as bad execution rather than bad theory. And when you watch the hypnotherapy sessions, just how drastic they are, it’s like a magic trick, and these men look like miracle workers.

How could they not be? The way that hypnosis makes these men tick is like watching someone pull out the dev commands on another person and start overriding bad code.

I sincerely hope their recovery was lasting.

As subversive as it was, these dramatic shows of recovery are… well, they’re what I was saying before. This is the second act climax, the parts where the heroes overcome their obstacles dramatically and overcome them. It plays like that. And really, showing such optimism and hope for recovery has to be a good thing.

Like, that’s the thing here. If it can be treated by a doctor, if recovery is possible? Then it is an illness, like any other. It means it’s not right to write these people off entirely.

The movie ends with before and after cuts, these men at their first interview and how they are after ten weeks of therapy with their fellow soldiers, finally ending with their final discharge into civilian life. They arrived in ambulances and leave in busses.

It’s worth watching for a lot of reasons I can’t describe here, but so much of what I covered here should be emphasizing just how radical this was for the time period, and why something so profound would get so buried.

Before I leave you all, I want to talk about one of Huston’s friends and peers, William Wyler. The directors Wyler, Frank Capra and George Stevens founded Liberty Films, a studio designed to be an independent one for the directors to create movies without producer meddling.

1946 was an auspicious year for these men. As Let There Be Light was buried, It’s A Wonderful Life was released under Capra’s direction. It was buried by the other studios and commercially unsuccessful, even though it was nominated for five academy awards… you might have heard of it?

In the same year, Wyler managed to make a movie called The Best Years of Our Lives, into the box office. It follows the lives of three veterans finding it difficult to fit back into modern America. It was the story that America wanted, and needed, to see, and it sold 55,000,000 tickets in the US, and a further 20,000,000 in the UK.

It’s heartbreaking, and Wyler — who went deaf, flying with bomber crews during WWII to get so much of the footage you still see on the History channel — did a lot of brilliant, soulful work to capture the feeling of betrayal and abandonment so many of these veterans found for themselves, and managed to slip his past the ever-present censors unlike so many of his friends.

I highly recommend watching these two movies if you get the chance. Let There Be Light is on Netflix and in the US public archive, and the TCM channel still plays The Best Years of Our Lives every now and again.

If this sort of thing interests you, I also recommend highly a documentary series on Netflix called “Five Came Back”. It covers all these directors through World War II and it’s a truly inspiring watch.