Productivity

by Wholesome Rage | 10 February 2020

Hey, you know what’s normal, but shouldn’t be?

The idea that if you can’t monetize what you’re doing, it’s not worth doing.

I don’t mean that this is a thing other people tell me. Frankly, it’s something that other people try to talk me out of thinking. I can’t stop feeling that way, though.

It’s a very common problem, especially among content creators. It’s a reason why so many streamers and Youtubers burn out, people whose job is enjoying video games at a professional level This week, one of my favorite streamers, Beaglerush, had to take a holiday from his job of playing the games he likes five days a week, because he was feeling burned out.

Because, I can’t stress this enough, that old truism of how “If you enjoy what you do, you’ll never work a day in your life”? Doesn’t really apply to my generation, I don’t think.

Instead what we got was: “Make your hobby your job, and you’ll lose a hobby and lose the line between on and off hours”. Our work becomes our whole life. The reality of setting your own hours is that means you feel like you should be working every hour, and you have to justify any time off. You can’t make a work-life balance if you can’t make a distinction between the two of them.

People have material needs. Air, food, water, sleep, shelter. The things that keep you alive. But they’re not all you need—a sense of belonging, a sense of security, a sense of self-esteem are all things needed for people to be content, to not be depressed.

The problem is, we’re not even entitled to food, water and shelter. All those things cost money. There are government programs to help you; usually, but they often force you to pick two.

Forgive me if you’ve all heard this one before.

Here, in Australia, if everything goes wrong for you, you’re eligible for assistance payments of about $280 a week. That sounds pretty good, until you realize that a shoebox apartment here is still about $200 a week rent. You could also have a larger place and share it with roommates, but you’re not really going to be able to get cheaper than that. That leaves you $80 bucks a week if we’re being extremely optimistic, which is just $11 a day for utilities, food, transportation, and any of the small comforts that make life worth living.

That’s if you can find rent that low. Just because it exists, doesn’t mean you can get it. Heaven help you if you lost a job and don’t have savings.

The numbers look similarly dire in the UK and Canada, and worse in the US, especially if you get a medical bill.

I got a job. Like about half of Australians my age, I can’t afford to move out of my parent’s house.

And because my mother lost her job - a professional job, held for close to a decade - even staying in the family home doesn’t feel safe or secure. And for a lot of people, including me, there’s no more ground to retreat to.

I think a lot has been said about my generation’s depression. It’s been blamed on social media, blamed on participation trophies. Blamed on a bad attitude or coddling or laziness.

I think depression just looks like laziness from the outside.

When I talk to older people about this, they usually try to give me the sense that if I work hard enough, stick with it, and push through, everything will turn out alright in the end. Life might not be what you planned, or what you expected, but with enough effort you can make it through.

But I think we’ve kind of picked up that’s a bit bullshit, haven’t we?

The fact that anyone can succeed isn’t reassuring enough when, at the same time, everyone can’t. I’m scared, all the time. When I didn’t have a job, I was scared I’d never be able to get one. And now that I have one, I’m scared all the time that I might lose it. I have friends with better jobs—and they tell me of their fantasies of dying on the way to work. It’s the only escape they can think of.

That’s terrifying.

I think, if we’re talking about the ways social media is making us miserable, it’s not enough to say that successful people are unreasonable role models to compare ourselves to. We also need to see the role the internet’s played in keeping us connected to the people who’d drift out of our lives.

We can keep talking to the people who can’t afford to go out anymore, or so depressed they can’t force themselves to. We keep seeing the long blog posts and alerts for support from friends who can’t keep their heads above water. A third of the GoFundMe’s we see are people who can’t afford medical bills.

Poverty is real, and it’s looming, and it could eat any of us any second. Things might just turn out okay, but we know for a fact we can’t count on that.

We live in a place where all the safety nets have been cut, and we need security to be happy.

When that happens, when that’s the mindset you got? Being a workaholic is a natural response. Because it’s the closest you can come to a sense of security.

Your immediate needs are met right now, but if you don’t feel like that’s a guarantee, then the best substitute you can get is making sure that you’re doing everything you can, so you’re ready for when everything is kicked out from under you. You’re braced for impact.

But this is, in a word, exhausting. It’s endlessly pushing a boulder up a mountain, knowing you’ll be crushed under it if you slip. And if you’ve ever struggled to pay a grocery bill, lived the reality of not being able to afford food one day, you can’t forget how bad being crushed under it gets.

This is where we get back to this: The idea that if you can’t monetize what you’re doing, it’s not worth doing.

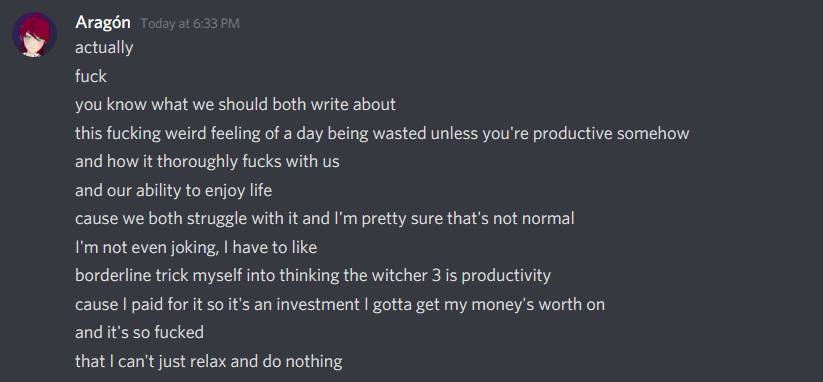

Aragon’s studying to be a judge, eight hours a day, six days a week. He is, by all accounts, an extremely productive person. But he sets his own hours to study, so every hour that’s spent playing a game is an hour that has to be justified.

Security is a more basic need than fun. It gets right of way.

I have to do this too - play tricks, rationalize behaviour. Most video games I play, I play while I listen to lectures or audio books, or else I feel like I’ve made myself less secure, less employable, than a hypothetical me who pushed through and studied. Time I enjoy is time wasted.

I find it hard to read fiction, because I don’t feel like I learn enough from it. It seems too much like something I just do for fun - and I can’t have fun if I don’t know where I’m going to live in six months. Not for sure.

But then, on any given day, I feel bad about not having read more fiction. I feel like it’s a side of myself I’m letting wither.

I used to write about how important learning to play piano had become for me, to relax, to pull myself out of deep depressions. I was playing an hour a day very consistently for months.

I couldn’t do that anymore when I learned my mum lost her job, my brother got his disability pension cut, and this house still has a mortgage. What I got from piano was that it was the one skill I never wanted to try to monetize, to perform for others. It was a private skillset, a personal one, just for me.

My attitude about playing piano isn’t what changed. The context of playing piano did. Trying to spend time on a skill I wasn’t going to monetize went from relaxing to immensely stress and anxiety inducing. Because even maintaining the skill I’d developed felt like time wasted. Self-actualization? That’s right at the top of the needs pyramid. Everything else has to come first.

And I think that’s the context that all your favourite artists end up having to bring to their work, even a lot of the ones that make it big. It’s never enough to be able to support ourselves - we need to know we can keep supporting ourselves, keep doing this.

And if we don’t know that - if we can’t know that - then all work and no play is the bandaid holding Jack together.

I don’t think it’s a healthy mindset. I don’t think it’s a safe or a sane one. But I don’t think there’s anything we can really do to deal with it until the threat of debt and poverty isn’t so constant, and pervasive.