On Britain

by Wholesome Rage | 23 May 2018

Britain and the United States are looked at very fondly by a lot of Australians I know. We feel like we’re sort of sandwiched, culturally, between Britain and the United States. In a lot of ways we are unable to come out of the shadow of either, our culture can often just appear to be a synthesis blend of those two larger nations.

It’s far more common to criticize the US these days. They’re the big, flashy, showy catastrophe right now, with Donald Trump pulling the biggest Leeroy Jenkins seen in the first world. But just because the United States is exploding spectacularly doesn’t mean that the rest of the world isn’t also succumbing to its own insidious internal collapses.

I think, as an Australian, I’m of a unique nationality to point to the seeds of the United States current downfall in Britain, where we share our colonial roots. To have an appreciation of British culture, and see the same seeds in my own nation, without being too immersed or sentimental towards it.

So when I say Britain is insidiously succumbing to internal problems, what do I mean by that, what can I point to as examples, and what can we learn from it?

1: British Law and Order

This could be a very short section, just in terms of how little I need to say to convey how big these problems are.

The United Kingdom has two major courts for crimes. Magistrates and Crown, where the Crown is for serious offenses that may need a jury or for anything where the sentence would be more than 12 months. For everything less, there is the Magistrates, who were responsible for 356,000 cases in the fourth quarter of 2017, compared to the below-30,000 that is seen by the Crown Court.

What this means is that more than 90% of crimes in the UK will be tried in the Magistrates court, the cheaper, cheerier equivalent. This is especially relevant because of the existence if triable-either-way crimes, where some crimes may be tried in either the Crown or Magistrates court when it’s not clear-cut.

The Magistrates takes an assembly line approach to justice. Whereas the Crown will have one case tried over multiple days, Magistrates try to handle multiple cases per day. They’re cheaper to run per day as well. There’s a big problem, though.

Like, comically dystopian.

England clings to its class system. Where its colonies have had the opportunity to have had a rebellious teenager period, England has kept a lot of its baggage and legal artefacts and, well, the Magistrates were originally meant to be judged by the landed gentry. The aristocracy, since they were supposed to be the benevolent dictators of their localities. The people with the education and refinement.

This tradition continues in that its Magistrates judges are middle-class volunteers.

No. No, really. There’s less than 200 practicing District Judges in the Magistrates courts, and the other 35,000 magistrates are volunteers from the community who have performed community service in the past. This means that 56% are over 60, and only 14% are under 50. Only 8% are black or an ethnic minority.

They are volunteers with the power of a District Judge, and to emphasize just how abhorrent this cost-cutting approach is, I would like to quote an anonymous English barrister.

In order to become a District Judge, you need to have amassed a law degree, a postgraduate legal qualification, vocational training, at least five years’ legal practice as a solicitor or barrister, plus usually two years of sitting as a deputy (part-time) District Judge. This adds up to at least ten to twelve years of experience in the law, which is vital; magistrates’ court law and procedure is rammed full of quirks and technicalities – many of which, incidentally, don’t apply in the Crown Court – and DJs are often drawn from the shrewdest, sharpest solicitors familiar with obscure legal technicalities that baffle day-tripper barristers visiting the magistrates’ court. The application process for DJs is protracted and punishing, comprising an examination paper traversing the darkest, most technically fiendish plains of criminal law and procedure; a panel interview, where an experienced judge will mercilessly scrutinize your powers of critical reasoning, logic, deduction and legal analysis; and a role play simulating a courtroom environment to assess your temperament, judgment and ability to cope with the chaos of the unexpected. You will also require professional references attesting to how splendid a lawyer you are. Experienced solicitors and barristers often have to go through the process multiple times, over many years, before they are deemed ready to exercise the judicial responsibilities that accompany the office.

To become a magistrate, exercising the same powers in criminal cases, you need to fill in a form, attend an interview, demonstrate that you’ve done some charity work and show willing to sit for thirteen days a year. If you make it through the interview, you receive eighteen hours’ ‘induction and core training’, during which the rudiments of magistrates’ court procedure and the art of judging are explained, and then after three visits to watch a mags’ court in action, you’re away. Your performance will be appraised once every three years, and this appraisal is limited to a single day’s observation, often by someone you know.

From: The Secret Barrister: Stories of the Law and How it’s Broken

If you are a British reader of mine and would like to volunteer, click here to find out that it really is that easy to become a judge!

This is also amid further budget cuts and austerity measures to the British police force, who are expected to lose 6% of their total budget by 2020, and lose 3,000 of its 120,217 officers. This is at a time when crime has gone up 11%, and, to quote the Guardian:

There was some comfort for the government in the report, with the inspectorate finding police could spend their money more efficiently, but most forces – 32 of 42 assessed – were scored as good or outstanding on efficiency. Ten required improvement and none were failing, in the inspectorate’s view. But the report’s findings seemed to mostly bolster the police case.

But there’s another interesting case here beyond response to violent crimes. What about the procedures that are still essential, but draw less attention? The Disclosure and Barring Service, the criminal background check, has been forced to have more and more resources pulled from it to make up for other areas. The average response for a basic check to be employed as, say, a nurse or school teacher is now averaging 77 days, nearly three months.

In short, crime is going up, the courts are packed and staffed with volunteers and the response has been… further budget cuts and austerity measures.

2: British Healthcare

There have been some ads in Queensland recently about not using hospitals unless you’re really sick, because they’re full. This is usually blamed on people being stupid and selfish, and so the ads are to ‘educate’ them. If I were being overly cynical, I would actually say that these ads are an attempt to blame poor people for the problems the hospitals are facing, as a cheaper alternative to increasing hospital funding to meet demand.

It’s something I see happening in the United Kingdom at the moment, and I’m told they’re getting very similar information.

So why do I say poor people?

I want to make a broader point here. Preventative medicine is great. It is much cheaper to get checkups and prevent problems from getting worse than it is to treat them after the fact. If you make a price barrier to healthcare, people will gamble on their health: There is a guarantee of a large expense for seeing a doctor, but no guarantee that the appointment is worth it. When the medical problem becomes more serious as a result, it then becomes a larger burden on the greater system to fix, and makes a worse impact on the individual who lost the gamble.

In England and Australia our hospitals are free, but our clinics and doctors aren’t. Here there was the practice of bulk-billing — doctors sending the bill to the state — but they’ve been getting heavily discouraged from doing that anymore. So more people are going to the hospital — always free — to get their healthcare because it saves them money.

Thus instead of taking the systemic solution — make the clinics and general practitioners fall under the state single-payer system as well, raising taxes to accommodate — there is the shifting of blame onto the individuals who have been forced into making calculated decisions within the system.

Part of this calculated decision goes even further. The neoliberal economics philosophy so fiercely harboured in England dictates that the free market is the most efficient solution to problems, and the best thing the government can do is step out of the way.

So what we see is a vicious cycle: The neoliberals cut healthcare, for austerity measures. This makes the state-run hospitals less efficient. They ‘punish’ the hospitals by cutting their budget further, to ‘encourage efficiency and reduce wasteful spending’. This causes the hospitals to operate worse, again.

At some point towards the end of the cycle, as we’re seeing now, the neoliberals use this as proof that the government is inherently inefficient, and try to privatize it and let the free market fix the problem. The free market then immediately jacks up their prices, and the neoliberal government points to it as a shining success as poor people become priced out of basic healthcare.

This is a common routine, as we will see with telecommunications, power companies and — as I’ll talk about later, in more specific detail — the trains.

Right now we’re at the end of the cycle.

To quote James Bloodworth:

In 1979, 64 per cent of residential and nursing-home beds were provided by the NHS and local authorities. By 2012 that figure had plummeted to just 6 per cent.

Most care in the UK is also provided by nursing staff on the minimum wage, operating on zero-hours — that is, no guaranteed minimum hours — contracts, and are done by lowest-bidder companies, meaning quality of care for the elderly and disabled has plummeted, mistakes are being made, the industry turnover rate for nursing is 25% per annum, and… blargh.

Seriously. Vulnerable people are suffering and dying right now because of austerity measures to healthcare, and it’s being blamed on poor people and immigrants.

3: British Trains and the folly of ‘free market’ capitalism.

Let’s focus a bit more on that privatization part there.

In theory, privatization is good because a nationalized industry has no competition and is a monopoly. It makes it slow, sluggish, and doesn’t incentivize it to innovate and improve. In theory.

In practice, we can look towards the British rail network.

So first, the train companies don’t actually own the trains. The trains and carriages are owned by rolling stock companies which lease the trains to the train operating companies. Free market! In theory, this means that there’s competition between the leasing companies, driving down costs, right?

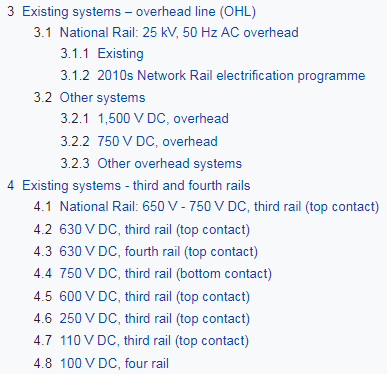

Except that England has many different types of rail, each only taking one kind of train.

For example, take just the variety of electric rails.

So the operating companies are often limited to one type of train to one type of track, limiting meaningful purchasing decisions.

Next is the issue that you can’t really run competing train services on a shared track. Historically that ends very badly. So, instead, sections of track are leased to operating companies, giving them effective local monopolies on services.

Now, instead of having one large, co-operative, nationalist monopoly you’ve created a cracked-glass cobweb of local monopolies neither competing nor co-operating.

This also means that changes to the system now require — instead of the government just making the change — collaborating with potentially dozens of fragmented private entities, all with a profit motive, making system-wide upgrades far more onerous than they otherwise would be.

Now, as Shawn puts it, a Glasgow to Edinburgh season rail ticket costs as much as a season ticket for the entire German rail network.

Damningly, the British idea of privatization has not been adopted by any other EU nation that has studied it.

On a final note, large parts of the British system have been bought up by foreign nationalized rail companies. 70% of South Western Railway is owned by MTR, or Hong Kong rail. Arriva are owned by Deutsche Bahn, and the French own 35% of GTR, Southern Railway’s parent organization.

Similar stories can be found regarding British electricity and healthcare privatization.

The love of the free market and loathing of state interference might be what led to the LIBOR — London Interbank Offered Rate — scandal being so damaging. LIBOR allowed banks which set interest rates to heavily invest in derivatives markets valued by the interest rates they set. The banks were found to be colluding with each other to bilk insurance and pension funds, and rob the market.

A speech Gordon Brown, a Labour politican, gave in 2005:

“Not just a light touch but a limited touch, helps move us a million miles away from the old assumption — the assumption since the first legislation of Victorian times — that business, unregulated, will invariably act irresponsibly. The better view is that businesses want to act responsibly. Reputation with customers and investors is more important to behaviour than regulation, and transparency — backed up by the light touch — can be more effective than the heavy hand.”

This was a speech given in an explanation for largely deregulating banks, and not enforcing what regulations remained. The year was 2005.

4: Income Inequality

I’ll start this with a quote by economist Thomas Piketty:

You need some inequality to grow… but extreme inequality is not only useless but can be harmful to growth because it reduces mobility and can lead to political capture of our democratic institutions.

Let’s call this the lightning round. Here are some choice quotes from Hired by James Bloodworth, the angriest I’ve ever been reading a book.

The bottom fifth of the population are 40 per cent less likely to go to university than the top fifth.

In recent decades the UK economy has been creating low-skilled jobs at a faster rate than high-skilled jobs. Between 1996 and 2008, for every ten middle-skilled jobs that disappeared in the UK, around 4.5 of the replacement jobs were high-skilled whereas 5.5 were low-skilled.

A 2015 report by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development found that more than half (58.8 per cent) of graduates were in jobs that did not require a degree.

Meanwhile, around 4.3 million working families are in receipt of benefits or tax credits. Most people living in poverty in Britain today are going out to work.

In 2015, 38 per cent of workers earned less than the amount the average homeowner made from the increase in the value of their house.

As to the rise of zero-hours contracts:

The answer is that, aside from effectively paying employees less than minimum wage, it doesn’t look like the company broke any laws. In fact, the reason it was able to get away with “treating workers as commodities rather human beings” was because employees were made to sign up to punishing contracts that left them powerless.

While 10% of workers overall say they would like to work longer hours, the figure rises to 37% for those on ZHCs. TUC research has shown that average weekly earnings for zero-hours workers are £188 compared to £479 for permanent staff, and that two-fifths earn less than the £111 a week needed to qualify for statutory sick pay. This is not “flexibility”: it is exploitation. And it is on the increase.

These contracts also give the opportunity for at-will firing, for any reason, and are often associated with a ‘3 strike’ policy that makes workers too scared, or simply unable, to improve their workplace situations. As well, secondary strikes are illegal in the UK, meaning that more stable workers are outlawed from striking on your behalf.

Because of the fear of unemployment, and the cutback of jobseeker benefits and the social safety net, employers are gaining all the power in relationships, and employer/employee relationships are becoming more one-sided.

Finally, I’ll finish on perhaps the most damning quote I’ve read about the British media. It’s a small thing. It was from an article I read a while ago and I can’t seem to find it again, so I’ll have to paraphrase.

When Jeremy Corbyn’s media team was asked about a recent upswing in the polls, they were asked what they thought contributed to it. The response was that the election period had started, which meant stricter media ethics regulations were actually being enforced ‘they had to tell the truth for a change’.

So what’s the rest of the time look like?

But British media deserves its own article another time.