A Sympathetic Protagonist doesn't have to be Likable: Spider Jerusalem

by Wholesome Rage | 19 December 2017

Transmetropolitan is a comic by Warren Ellis that is fantastic. It’s enthralling, it’s brilliant in the way truly good speculative fiction should be; It tells an interesting hypothetical future that’s a dark mirror of our current values, our current society.

But that’s not what I want to talk about it.

Transmetropolitan’s protagonist is Spider Jerusalem, a man most accurately described as Hunter S Thompson by way of Nietzsche. In fact, Transmetro is a sort of counter-culture adaptation of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. A wise man descends from the mountain to speak his truth, then returns to the mountain again.

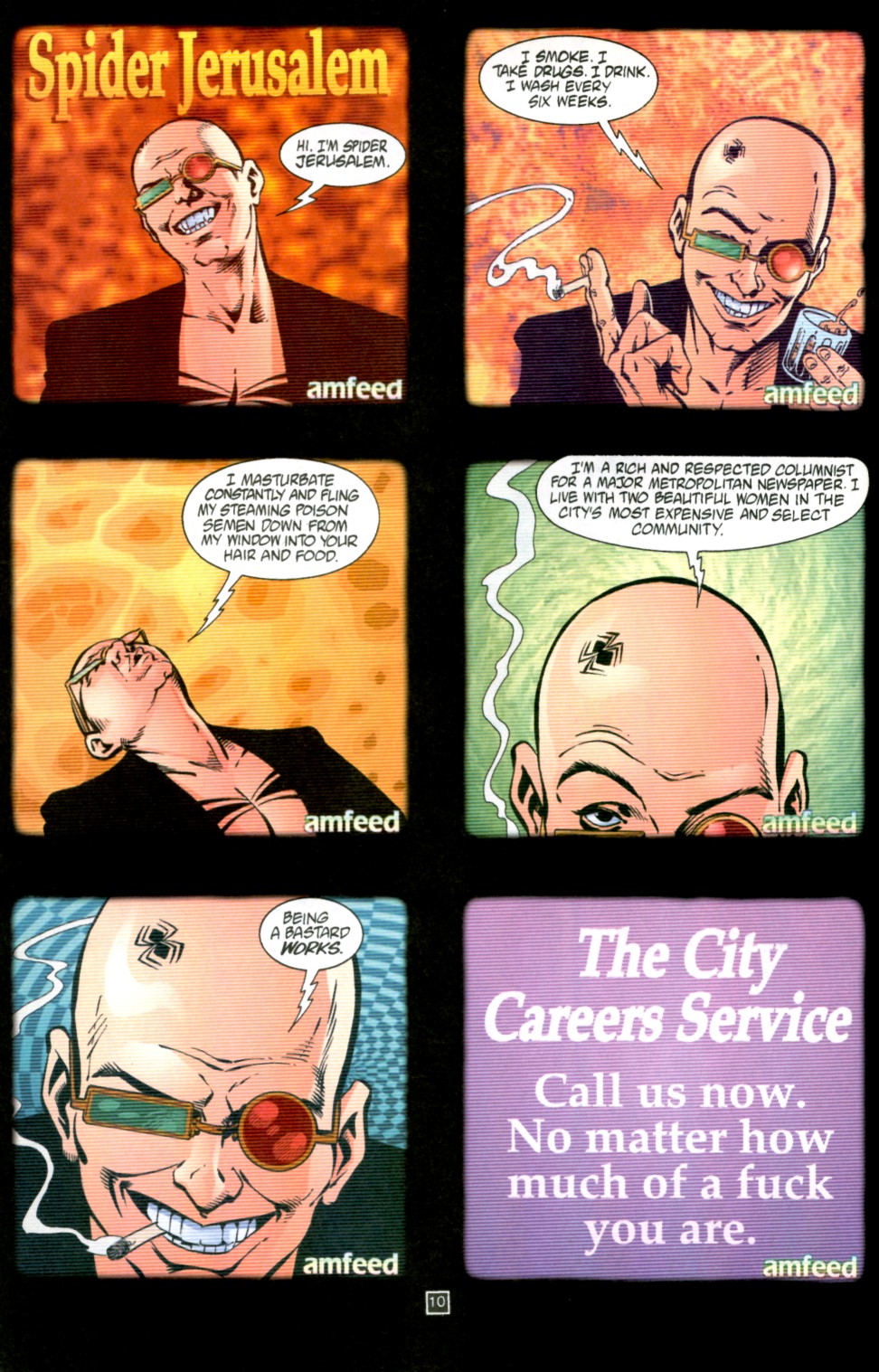

Spider is a huge bastard. His defining trait, in fact, is being the biggest fucking asshole to absolutely everyone, all the time, forever.

So who better than the king of bastards to speak about why your protagonist doesn’t have to be likable to be sympathetic?

Now, that being said, I love Spider Jerusalem, I truly do. As I said in a previous article, a good protagonist should read as a philosophy on why it’s desirable to be that person; Not necessarily that you would want to be that person, but why you’d immediately understand why they would.

Spider Jerusalem is miserable, and bitter, and angry, and cynical, and awful. He has few meaningful friendships, and he doesn’t desire more. He’s hedonistic, wallowing in a pile of mind altering substances and caribou eyeballs. All he truly wants is to be left alone with a pile of porn and guns.

This is obviously a very understandable character. We get that he’s the worst of our unchecked, most base and primal impulses. That’s… not very respectable, or an ideal we should want to live up to, but it’s an understandable and honest one.

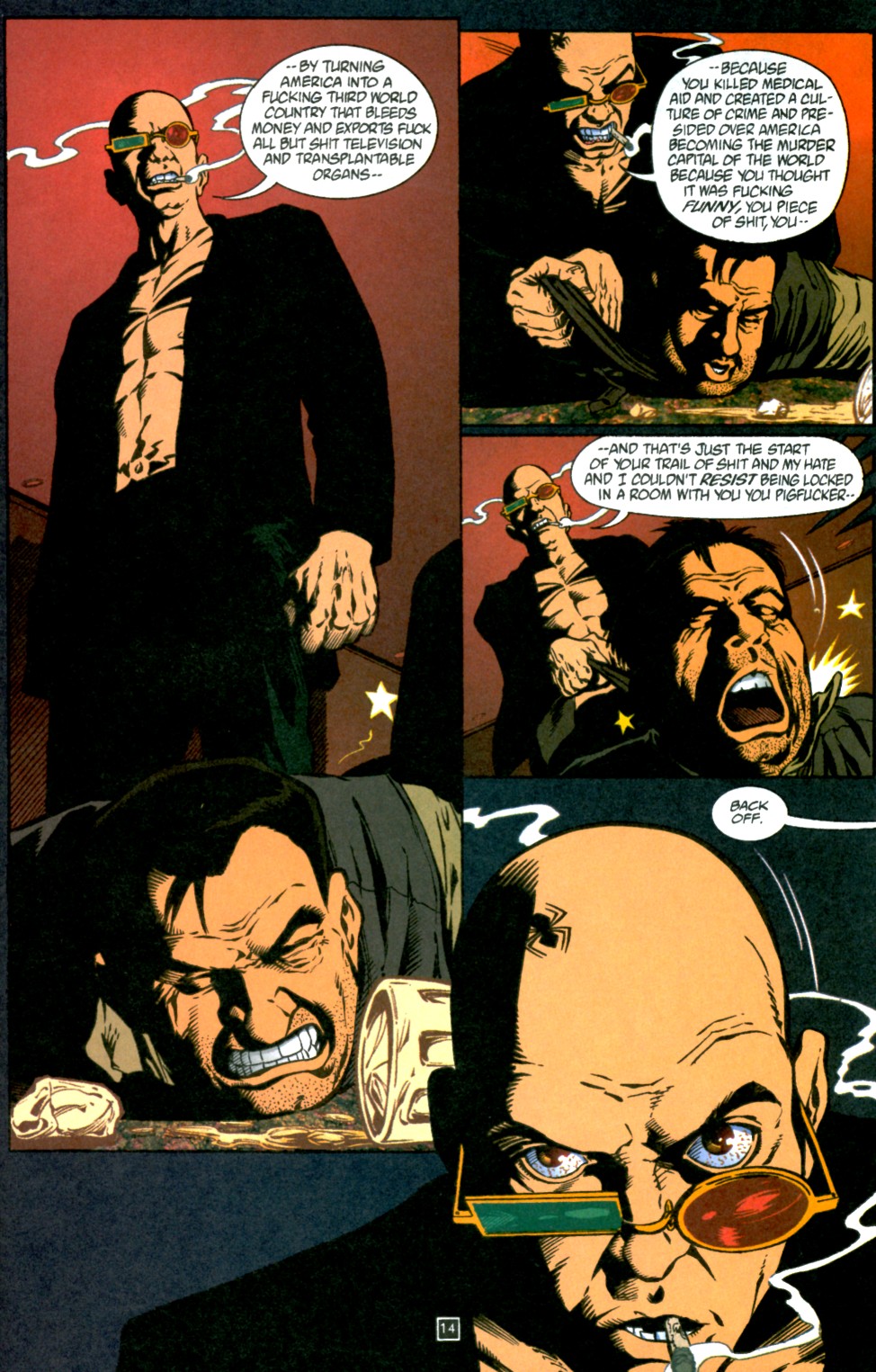

All of this, however, stems from Spider Jerusalem’s twisted idealism. He truly wants the best for people, and for people to be better. He’s a goddamn, motherfucking journalist. He’s shown to be open-minded and extremely empathetic. He doesn’t doubt that people can be good, and when he meets people he finds to be good he comes across as… humble, kind, respectful. A patient listener.

All he wants is the Truth. He wants people to be honest, to be good, to be better. He sees the people who do good get trampled and abused and even murdered by assholes and bastards, and he hates it. He abhors it. Why did he go up to the Mountain, leave society behind? Because the people loved him, and bought his book covering the election of The Beast — the president at the start of the comic — and vote him in anyway. His election coverage novel is a colossal bestseller, and everyone read it, but it didn’t change anything.

He’s a man that’s broken by a broken system. He’s not even screaming into the void; Everyone’s listening, but nobody’s acting. Ostensibly because they can’t in a polite society. Because they’re not willing to be bastards themselves.

You come to appreciate that’s why he’s such a miserable, bitter, angry, cynical bastard. He’s a crushed and wounded idealist who’s just… given up on being anything else. Those few times he believes he can make meaningful change are what drive him.

Problematically, to be a colossal twat to everyone who gets in his way.

Spider is my favourite protagonist of all time, of anything, ever. He’s not much to everyone’s taste. He’s a piquant protagonist, but he’s fantastic.

All of this is to say; it’s a very common misunderstanding that a character has to be likable to be sympathetic. Or that they have to be morally good. They really don’t!

It’s usually a reaction from authors who are told their characters need to have flaws to be interesting, go too far in the opposite direction, then overcorrect. Or advice given by people trying to correct people who write too unlikable characters.

It’s true that characters shouldn’t be unlikable for unlikableness’s sake; Characters that pull guns on people just because they’re mildly frustrated, have unchecked anger problems, are too hardboiled for you to understand… they’re a problem. Sure they are.

But it needs to be understood that it can also be a problem to push too far in the other direction. “The character has to be likable. They have to be good. They have to be nice.’

The end result is a character that can be seen as ultimately spineless. Being nice is only meaningful if it has a deeper reasoning, a deeper reason behind it.

However, just trying to make a flawed, asshole character isn’t an immediate fix. If they’re just an asshole, they’re just an asshole.

Compelling characters, truly compelling characters, need to be a blend of both. They can’t always be assholes all the time, but they can’t be pushovers either. Spider is an asshole, certainly, but he’s always an asshole on behalf of other people. He’s an asshole in a twisted form of justice and empathy. We’re shown that he cares, and he does a lot of things that are caring.

He has a third dimension like that. We understand the bastardry as coming from a place of intense caring, of frustration at the human condition, and we have depth to the significance of the kindness by seeing how much of a bastard he is even in situations where he’s shooting himself in the foot by doing so. We know it’s not artificial. We can see it’s genuine compassion, because kindness is never a tool he uses to get what he wants.

Spider Jerusalem is shown to be a bastard, but also capable of sincere kindness. So we see him as a complicated, conflicting individual.

Captain Carrot from Pratchett’s Discword series is another example from the other side of the spectrum. He is always kind, reasonable, compassionate. He’s the kind of man that stops a war by encouraging both sides to engage in a healthy game of football.

He lies, if it stops greater violence. He tells half truths with a completely honest face. Because people expect the best of him, they never expect the lie. They don’t think to analyze him.

Carrot is a good man, who is willing to do dishonest or violent things if he believes that it is for a greater good. Sometimes that’s telling a bit of a fib. Sometimes that’s stabbing a man that needs stabbing, regrettably.

Carrot is a fantastic character because he’s truly good man who is also forced to be a policeman. And a good copper can’t always be honest, and a good copper can’t always be non-violent. When he’s forced to act against his nature, he does it without grumbling, because his belief in goodness is more important than superficial acts of goodness.

Carrot’s a cop, because even though it forces him into situations that make him act against his better nature, it’s the position that allows him to do the most good for the most people.

Spider Jerusalem is a fantastic character because he’s a true bastard who is capable of being truly good and kind in ways we should aspire to, but he’s usually not. He’s incapable of being that good person because of the perceived failings of the society he lives in. He can’t be good and happy until there isn’t a society causing immense suffering to those around him.

He’s a journalist, because if all he has is a gun with a single bullet in it, he’s going to try to blow a kneecap off the entire goddamn world.

Great characters don’t need to be likable. They don’t need to be unlikable either. They need to show the struggle between actions and beliefs; They need to be a philosophical statement on why a person would want to be that character, why that character wants to be themselves. Then they need those beliefs to be tested and conflicted, so you can see what truly matters to them, what they value, and why.

How their actions, likable and unlikable, tie into their beliefs.

Characters are in the conflict. Characters are in testing their values. Characters are the hypocrisies that reveal the true underlying person. Characters change under pressure – and that can be for better or for worse.

And sometimes? Sometimes writing a bastard works.