Sewers and Surgeons

by Wholesome Rage | 28 December 2017

Up until now, this blog has primarily been focused on giving writing advice. However, an important part of writing is knowing interesting things and reading a lot.

Like a toddler’s sticky fingers, you’d be amazed at what gets picked up. I love history, and I’m a huge fan of the industrial era in particular. It’s my favourite period of history for a lot of reasons; It’s the birth of rationalism, when people believed that science really could save us all, when we finally got brilliant minds together and figuring out the mechanics of the universe for the first time. Technology exploded, and with it the migration from agricultural subsistence living to truly urban cities and a much higher standard of living… sort of.

Just to put it into perspective how fast technology exploded; The first recorded journey by steam train was 1804. The first powered flight was 1903. We put men on the moon in 1969.

We went from the birth of automation to the space age in only 170 years. And every step in between, every decade, is fascinating! It’s a rapid explosion of using tools to make better tools to make better tools. It’s of society changing to adapt to the importance of those new tools. And every step of the way, every incremental transition, has its own quirks and charms and layers.

It’s a time when countries declared war on miners fighting for better conditions, whether it be Australia’s Eureka Stockade, or the United States’ Battle of Blair Mountain. When feudalism gave way to indentured servitude with institutions like the “company store”, but people finally had the economic freedoms to fight back against those practices, to unionize.

It’s a period of shift towards equality for all, and the concept of intellectual labour. It’s a time when we genuinely believed the world could, and should, get better for everyone.

For better or for worse, the industrial era is when we came into our own. We developed languages we could use to speak to machines, and we told them to work for us, and our machines obeyed us.

And for the first time we began understanding the machinery we were made of, as well.

Cholera first hit Britain in 1831, claiming around 6,500 lives in London. Without treatment, mortality rate was around 50%, but the revolutionary invention of rehydration intravenous therapy, and salts, brought that down to less than 1%.

Until the next big outbreak of 1848-1849, which took 52,000 lives.

London believed the outbreak was the result of ‘bad air’ - people were getting sick because the city reeked. In less than fifty years, the population had doubled. It famously boasted more Irish than Dublin, more Catholics than Rome. With all these people came disease, and the infrastructure was still based around the Roman sewers.

During periods of heavy rains the sewers would overflow into basements and flood streets and houses. Septic tanks constantly leaked into the drinking water. People were getting sick.

Here we come to our two key historical figures you’ve unjustly never heard of. Sir Joseph William Bazalgette (pronounced “Bazz-ill-jet”) and Dr John Snow.

We’re going to be bouncing around time a bit, so stay with me. We’re lucky to have such a wide angle view of such things, it’d be criminal not to take advantage of our perspective.

Doctor John Snow is a contemporary of another fellow, Doctor Robert Liston. This detour is just to give you a jaunt through the time period, so you understand where surgery was by this point. It also gives me an excuse to share my favourite anecdote of all time.

The ability of a surgeon back then was measured in their quickness, in their efficiency. No anesthetics, no antiseptics, it was just how quickly you could amputate, clamp the arteries, seal the wound with hot tar. Robert Liston was a remarkable surgeon.

The author Richard Gordon noted that Liston could perform a complete amputation in two and a half minutes, but his record was actually twenty eight seconds. Liston was an amazing, remarkable man. I highly recommend reading his Wikipedia page in full, at the very least.

In fact, I’m just going to quote Dr Liston’s Wikipedia page liberally, to explain the attitude of the era.

At an address by Dr Oliver Wendell Holmes to the Boston Society for Medical Improvement on 13 February 1843, his suggestions for hygiene improvement to reduce obstetric infections and mortality from puerperal fever “outraged obstetricians, particularly in Philadelphia”. In those days, “surgeons operated in blood-stiffened frock coats – the stiffer the coat, the prouder the busy surgeon”, “pus was as inseparable from surgery as blood”, and “Cleanliness was next to prudishness”. He quotes Sir Frederick Treves on that era: “There was no object in being clean… Indeed, cleanliness was out of place. It was considered to be finicking and affected. An executioner might as well manicure his nails before chopping off a head”

So here we get to the reason I thought of Liston, though. And here I again I quote Richard Gordon, via Wikipedia, for perhaps the best line recorded in human history (beyond Travis McElroy’s nine word; “I dropped a fidget spinner on my baby’s head”)

…amputated the leg in under 2 1/2 minutes (the patient died afterwards in the ward from hospital gangrene; they usually did in those pre-Listerian days). He amputated in addition the fingers of his young assistant (who died afterwards in the ward from hospital gangrene). He also slashed through the coat tails of a distinguished surgical spectator, who was so terrified that the knife had pierced his vitals he dropped dead from fright.

That was the only operation in history with a 300 percent mortality.

This was one of the most brilliant, most respected surgeons of the time period, and I sincerely mean that; as silly as that story was, this is just what surgery was before Sir Joseph Lister — what that quote means by pre-Listerian days. You’ve heard of Listerine, the antiseptic mouthwash? That guy — and the Listerian days weren’t until the 1870’s at the earliest.

Yeah! The concept of washing your hands before and after surgery was still controversial to the field of medicine in the year we invented electric lighting! I mean, you probably half-remembered that at the back of your mind, but it’s still mind-boggling to realize how fast things moved towards the end of the 19th century.

And all of this should frame context to how ahead of his time, how controversial, Dr John Snow was in his time. Snow died of a stroke at the age of 45, 1858. He would never live to see vindication for many of his studies into epidemiology. His best works were published posthumously. He was considered a crackpot for only drinking boiled and purified water.

What John Snow was recognized for in his own time was anesthesiology.

You see, before Snow and some others, ether was commonly used for vaudeville performances. You know those Youtube videos of kids high after seeing the dentist? Basically that, as live theater.

A dentist saw one of those performances, during which a man got punched in the face and didn’t feel it, laughed it off.

And one of his teeth was knocked out as the man laughed.

And he realized…

It was a novelty, a stage amusement, before that dentist realized the potential of it.

It was Snow, though, who I believe more than anyone else was responsible for the modern field of anesthesiology. He might not have been the one to make that first connection, but he was the one that:

1) Studied it intently, figuring out safe and effective dosages.

2) Designed the breathing apparatus and delivery methodologies

3) Made it popular among the public.

So let’s forget for a moment that he published On Chloroform and Other Anaesthetics and Their Action and Administration, which is kind of a huge thing to forget for a moment but let’s forget it.

Snow made anesthetic popular by acting as Queen Victoria’s obstetrician. Now, before then, chloroform was… well it was effective, but lesser doctors had a nasty habit of flat killing you with it (see the importance of that publication above, which we’re forgetting about for the moment), and this guy was so confident he’d gotten it down, he was asked to use it on the Queen. During childbirth.

Snow had worked out the right dosage to keep his patients partially conscious, so they only feel the first half of the contraction during delivery, but were still capable enough of listening to their doctor’s instructions.

All this means that the Queen not only survived, but enjoyed the experience, saying he made childbirth ‘pleasant’. This was a huge deal! After that the middle class started to follow his lead – good enough for the Queen, after all.

However, this first time in 1853, the medical community widely criticized his perceived recklessness.

Which is why it’s so important that the Queen trusted him enough to do it again, for her last child in 1857. Snow would die a year later.

Snow fought his whole life for a lot of his work to be recognized by the medical community, who were staunchly against so much of his work. Anesthesiology was a battle he won in his lifetime. Epidemiology… cholera was not.

Now we go back to Sir Bazalgette in 1849.

Joseph was employed by the London’s Metropolitan Commission of Sewers in August of this year. He was thirty, now, but in his lifetime he’d already done major work as an engineer for the railroads, and had experience in land reclamation and drainage — some of those years in China. He’d been running his own consultancy practice since he was 23.

His first task was to assess London’s old sewers, brickwork old as the Roman era. It was mostly designed to carry off surface water. Sewage was otherwise dumped in cess pits or carted away as ‘nightsoil’ for farmers to use as fertilizer, or tanners to use for higher quality leather than they’d get from the horse manure that was also a constant of London streets.

The increasing popularity of flushing toilets — “water closets” — was also proving to be a problem. The old drains weren’t designed for the constant output of sewage modernized plumbing was creating. In heavy rains, the drains backed up, flooding basements and streets with liquid waste.

The people turned to the Times. 54 letters were published begging for something to be done.

The Metropolitan Commission simply didn’t know. So it wrote its own letter to the Times, asking people what they thought they should do.

It was Joseph Bazalgette’s job to sort through the replies.

All 137 of them.

None of them were particularly helpful. One suggestion, even, was to build a tunnel underneath the Thames… lengthwise.

Fortunately, Bazalgette was a dedicated man. His obsessive work on the railroads at their time of most expansion resulted in him having such a nervous breakdown he was forced to retire to the countryside for a year to recover. That was less than two years ago.

Meanwhile… oh, boy, this gets a bit hard to watch, with hindsight.

Leading health authorities like Florence Nightingale, bless her heart, believed disease was spread by smell — ‘miasma’ — and so they tried to clean London of the smell, thus curing it.

Parliment ordered the sewers flushed into the Thames, to rid London of the miasma smell, in spite of dire warnings from a Doctor John Snow, of the newly-founded Epidemiological Society of London.

Sometimes reading history books is like watching every scene in every horror movie where they’re about to go into the obviously-haunted-house all at once. Maybe it’s because history is built on an ancient native burial ground or something.

Okay so at this point I should also explain why cholera is so deadly. Basically it clings to your small intestine, then reproduces there happily, clogging up the bits that your intestines use to absorb liquids. Your body recognizes it as an infection so it tries to flush it out. It flushes it out like a normal gut infection, which means it overcompensates and doesn’t take into account that it’s not reclaiming water from the acute diarrhea. You dehydrate very quickly as a result, usually dying within 48 hours.

It is an awful, horrible, nasty way to die.

And it’s a waterborne bacteria. Spread through fecal matter, just as Dr Snow was warning everyone.

And they just flushed everything, everything into the main river.

There were riots through Paris and London as the poor didn’t have room to bury their dead, such was the epidemic at this point. Homes were filled with fresh cut onions to mask the smell of dead relatives.

Here we circle back to the beginning. It’s 1849, and 14,000 Londoners have died this way.

Sir Bazalgette had three sons by this point, ages four, three and one. His work in the sewers wasn’t glamorous by any means, but the man was a dedicated engineer, and he believed the work he did might be the difference between his children’s life or death. Finishing the sewers would free London of the contagious miasma smell, which took lives so randomly.

John Snow, at this time, noted that an epidemic would hit one side of the street and ravage a housing block, but leave the houses on the other side barely touched. If the occupants were breathing the same air… well, it just didn’t make sense. He got to work proving his theories on the importance of clean water, and the need for a new sewer system.

Snow and Bazalgette worked one street away from each other, but as far as we know, the two men never met.

In 1853 the disease returned. And here we come to the Broad Street pump in the Soho district of London, one of the most famous landmarks of medical history.

The Broad Street pump was renowned by locals for the pure, sweet taste of its water. Unfortunately, an infected baby’s nappy had ended up in the well water, leaked into it from an old septic tank three feet from the well, and that water became contaminated.

Snow tracked every case of cholera in the Soho district that he could, around all 12 of its water pumps. Only those around Broad Street had cholera cases.

He noted an army officer that dined in the area had drank water from the pump and was dead within hours. A coffee shop owner used the water for her customers, nine died the next day. A nearby prison had no cholera deaths; It drew from its own well. A percussion cap factory suffered eighteen, as it took two tubs of water for its workers to drink from during shifts. The brewery next door, which supplied the workers with beer instead, suffered no deaths at all.

Actually, that’s a fun little tangent. Culturally speaking, there have been two manners of making water safe to drink. In the west that’s been fermentation, which is to say making alcohol. The diet largely consisted of weak beers and ciders, as water was just far too dangerous. In the East, however, it was boiled, which is why tea is of such cultural importance and alcohol tolerance is a predominantly Caucasian trait.

For a lot of human history, alcohol was more survival than anything else.

Most interestingly for Snow was an aunt and niece who died in Hampstead, well away from the rest of the outbreak, in seeming isolation. It turned out the aunt so loved the taste of that particular pump water that she regularly had it bottled and brought to her.

Both had died the next day.

What’s astonishing is the rigour and determination Snow took to building this evidence. He made conclusive, ruthless maps of the Soho region, linking case after case to this same pump, showing it couldn’t have been miasma, that didn’t make sense.

Snow insisted that the pump handle be removed. Nobody believed his theory — that the little white flecks in his water samples were the cause of the outbreak — but they were willing to humour the good doctor by removing the handle as a temporary measure, if only to prove him wrong.

The cholera outbreak in the area stopped almost immediately.

The Committee for Scientific Inquiry Into Cholera did not agree with his conclusions; Obviously, it just meant that the impure waters of the pump acted as a catalyst for the miasma of the region.

John Snow was a crackpot, it seemed.

There was a particularly political and emotional reason to reject the findings, of course. Nobody wanted to admit that sewage so readily tainted all of London’s drinking water. Nobody wanted to believe that.

1856 again. Three years later.

Bazalgette became Chief Engineer of the newly formed Metropolitan Board of Works. It had been years of studying and thought and calculations. His project was to build a new sewer system.

He had realized London was built on the slopes of a valley. A sewer system that built into and around the old one, and carried it out to sea instead of into the river, would work just by gravity’s own power.

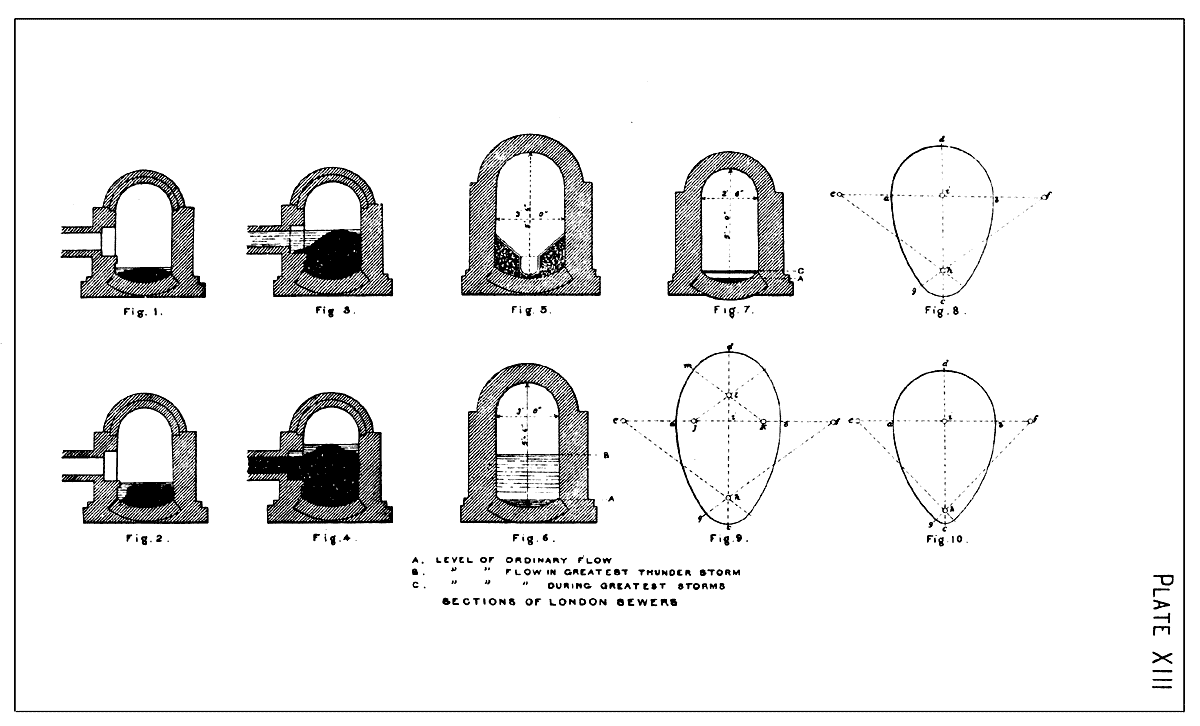

Armed with a rowboat, floats and a telescope, his calculations showed that the optimal gradient would be two feet down for every mile, to get a fluid speed of one and a half miles per hour.

Problem. That meant the tunnels going far below the river itself, which meant it would need to be pumped back up to ground level once it reached its destination outside London. There it would be pumped into great baked brick reservoirs, and released at high tide as the river was outgoing, preventing anything from seeping back up the river as the tide came back in.

John Snow had removed the pump handle three years ago now, and was still fighting for credibility of his ‘water-borne effluence’ theory. Bazalgette was still more worried about the smell than of contamination.

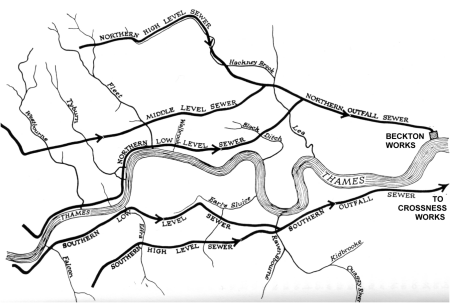

Bazalgette drew this:

Three main sewers to the North, and three intercepting sewers to the South.

1,100 miles of new sewers. 318,000,000 bricks. 3,556,000,000 kilograms of earth to be excavated by hand, by pick and by shovel.

All designed to hold the entire weight of London above them. All above and beyond what the government specifications were.

Of course, the plans were rejected. No budget was given.

Fives more times the plans were drafted and redrafted, five times the plans rejected.

Quoting the Times; “Why is it called the Board of Works if Mr Bazalgette has neither the money nor the power to carry out the works?”

And here we get to the good bits.

The Great Stink. The heatwave of 1858, after the sewers had been flushed into the river.

Parliment fled London. The air from fecal matter rotting in the Thames had grown so noxious the elected representatives feared for their safety, and damn their impoverished constituents. The few that remained treated the sealed windows with lime to prevent the noxious stink from getting in.

Cholera didn’t return with the stink. But the Great Stink was so horrendous it forced Parliments’ hand. Bazalgette was given three million pounds and told to start immediately, cheque in one hand, a handkerchief held to the face in the other.

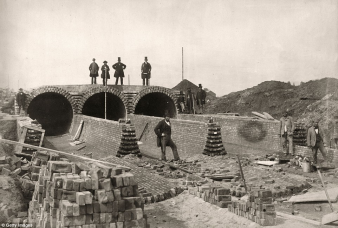

20,000 men took to it with picks and shovels. With charcoal furnaces backing bricks. Dig a trench, build the sewer, cover it over again at the high point… then it’d be down to mining in the metro area, where cut-and-cover wouldn’t cut or cover it.

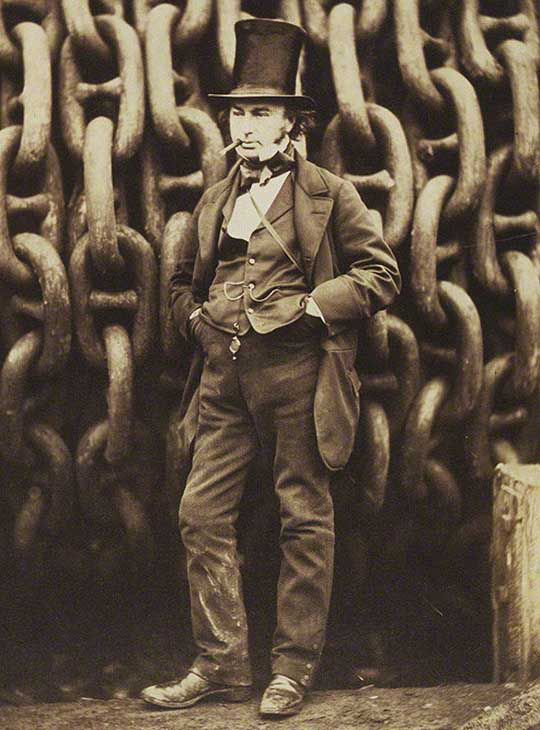

Bazalgette turned to a new material to bind the bricks that would hold London. It was more expensive, yes, but it suited his purposes perfectly. It was a relatively untested material called Portland cement. Sir Isambard Kingdom Brunel, his friend and colleague and just…

… just one of the most badass motherfuckers to ever walk the planet, seriously, he expressed many doubts about the viability of the new material. Bazalgette stood firm, hinging his entire reputation on it. Modern quality control methods were made here, too, to ensure the cement was mixed right in every batch – small changes in the mixture could change the strength of the final result dramatically.

Portland cement, by the way, is the stuff we use today. It’s small touches like this that make the industrial era so inspiring to me; It’s amazing what’s so ubiquitous was once considered visionary, revolutionary, risky.

Regardless.

This thing was built well, and built to last. Brick by individual brick.

Then you have the reservoirs they built.

God, I could just cry looking at this. I really could.

If you don’t look at this and feel a deep sense of pride for humanity, I can’t think of anything that would. This is a sewer resevoir; This wasn’t to be built for anyone to see. This wasn’t art. This wasn’t a show piece. This was just meant to be purely functional.

And yet.

And yet so much time, and care was put into every brick. So much brilliance was put into the geometry of this.

And it was built just to be endlessly shit upon, because that’s what it was needed for.

There is no glory to be had here, no dignity. Just resolute pride in a job well done, because it was a job worth doing.

Stripped of motors and engines and electricity and computers and plastic, we are still capable of this with nothing but sticks and mud.

That was all we had, and still we did this.

God.

Bazalgette was having a rough time. Less than ten fatalities were recorded through the construction of the sewers — that’s goddamn mental by those standards given the immensity of the project. Still, reporters continued to vilify him still, dogged by his days of being unable to get the project off the ground.

He invited them to a joining of two tunnels, two tunnels started seven miles apart. The workers dug with hand axes and shovels.

A newspaper at the time reports; “So accurate were their designs, that when the different bodies of men met, there was not a deviation of a quarter inch in their projection.”

During this time, of course, the James Watt company — and I could do a whole other article on them too — built the four largest steam engine pumps ever made.

Three months after the pumps were turned on, cholera returned to the West End. With the sewers clearing the smell, why had cholera come back? The East London water company, despite assurances that it filtered the water. Yet fresh eels were found it. The company was feeding sewerage-tainted water, and it proved one of the final undeniable nails in miasma’s coffin.

Dr John Snow, the man who broke the Broad Street pump, was finally vindicated, eight years after his death.

Bazalgette was fascinated by this turn of events. The development of the sewers was to remove the stench of London, the fog of pestilence, and the purification of the water supply had always been a secondary priority. But it was that which became the basis of the modern plumbing infrastructure today, and the saviour of so many from dying horrible deaths from entirely avoidable contagions.

But the pumps worked. Cholera never returned.

The pumps in the “Cathedral of Sewage”.

I had the good fortune to see an operating William Murdoch brewery pump in the Sydney science museum and I will admit, I openly wept. I stared at it fascinated, making lazy cycles, for fifteen minutes, my mouth hanging open. It was a religious experience for me.

It seems silly. It really does.

But think of it like this.

This is the last time in human history you could figure out the entirety of how something worked by just looking at it. If you watched it long enough you’d be able to draw a copy of it from memory, and figure out the rest. These pumps are brilliant, absolutely brilliant, and the mad Scottish bastards responsible for them have my eternal awe and respect.

When you watch these things move, then, you don’t see an impossibility. You don’t see something made by some alien Scientist or Engineer, a species so much like your own but just one step to the left of it. You understand what it’d take to make it. You see the rivets and welds, the precision of the gaskets and seals, and you understand what it would take to make it. You can see the design wholly, the implications of it, you could figure out the math of how hot you’d need to make those boilers to move how much fluid, really, because that would be easy to test, all you’d need to do-

You look at a working pump like this and you hear, click-click-click, all the pieces of the next two hundred years fall into place, each branch down the technological tree growing fuzzier and fuzzier as it grows more distant from this one piece you can understand, this piece that’s ultimately as quaint as a drinking bird toy, at the end of the day.

Less than ninety years from this pump being made, we would be performing the Trinity tests, proving we understood the atom itself well enough to break it.

The Crossness pumping station is a place of holy significance to me, if you’re of mind to worship the human spirit. It’s a reliquary of a place where people made the first real steps outward that would land us on the moon, and inward that would lead us to truly understand our own machinery.