The history of the Manhattan Project in 4,000 words and one footnote

by Wholesome Rage | 4 January 2018

When the bomb dropped in 1945, it’s important to realize what technologies had been revolutionary in the lifetimes of the minds behind the Manhattan project.

Automobiles — they were only just starting to be called ‘cars’ — aeroplanes, radio, film and television… in so short a time, people found that they were in the most enlightened period of human history. The world around them was moving so fast. Oppenheimer had been born less than a year after the Wright Brothers took off over Kitty Hawk, but he was only fifteen when he saw the first transantlantic flight.[1]

And yet.

And yet they had experienced two world wars in their lifetimes. Between them, at least 90,000,000 casualties. If you count famine and disease, probably closer to 120,000,000. That would have been 6% of the entire world population in 1940. Or, if you’d been Jewish, like Oppenheimer, around half of all European Jews had been eradicated.

Here they had given the world the tools with which to destroy itself completely, with mathematical efficiency, and they hoped that what they had done was the right thing.

Oppenheimer said;

It is perfectly obvious that the whole world is going to hell. The only possible chance that it might not is that we do not attempt to prevent it from doing so.

All this is preamble as to why the Manhattan project is one of the most fascinating feats of human science and engineering. In a time where science was doing so much, technology was advancing so far, it continued to be thrown into the war machine time and time again. Every time people said of new technologies; “War is over. No one would be terrible enough to fight, knowing this weapon exists.”

Time and time again those weapons were used.

Mustard gas, sarin, zyklon b.

Aeroplanes, tanks, cannister shot from artillery.

Not only were they weapons people had used. They had been used en masse on civilian targets.

At the Trinity test site, a bunch of scientists prayed that this time, this time, they would be right.

Famously, the scientists didn’t know whether the first bomb would set off a chain reaction that would continue ripping through the hydrogen in the atmosphere, and set the entire world on fire.

But if it worked exactly as intended, that might be the end result anyway.

The alternatives were grim, though. The casualties predicted for the invasion of Japan were at least one million. The amount of Purple Heart medals manufactured in anticipation are still being used today; They’ve lasted through Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq.

Men on both sides of the war turned to science. One man, Enrico Fermi, changed from one to the other.

After receiving the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1939, Fermi took his family straight from Stockholm to New York, where he was immediately offered a choice of five professorships. His work on statistical models and mathematical physics had been hugely important to the field of nuclear physics, including splitting the atom.

In the United States he continued his work on the idea of a chain reaction, atoms splitting that cause more atoms to split that cascaded outwards. The key was that previous nuclear reactions had generated one neutron per interaction, whereas his new work showed that you could get two from uranium. Work he had refused to do for Mussolini, he did freely in the United States.

The hopes were always that it would be used for nuclear power. Even in those early days, though, there was a grim recognition among the scientists that it’d be used as a weapon first. Better theirs than Hitler’s.

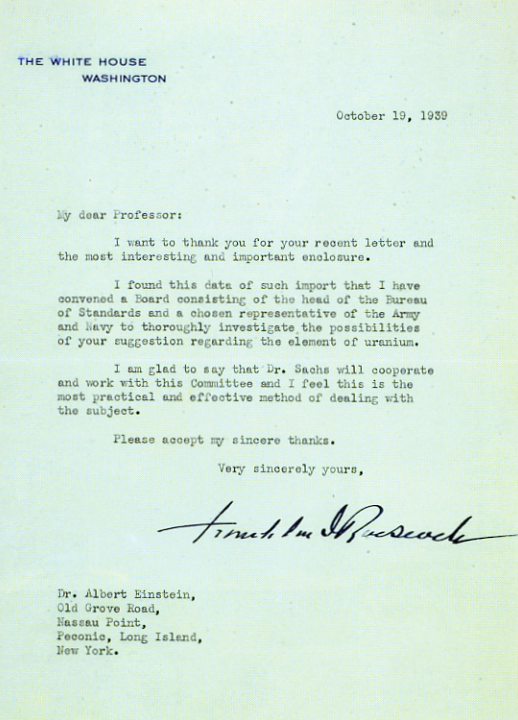

The scientists didn’t think the president would listen to the significance of “a few blips on a screen” — they took the results to Albert Einstein himself, already a pop-culture legend. Einstein quickly agreed with the implications; this was a doomsday weapon in potentia: “Daran habe ich gar nicht gedacht” — I did not even think of that.

So was drafted the Einstein–Szilárd letter, with Szilárd being one of the scientists who had teamed up with Fermi to split uranium. His paper to Einstein showed the significance of the results, and Einstein’s signature showed that he both confirmed and agreed with the findings.

Part of the fear was that Germany would also be working on the technology, and Hitler’s richest source of uranium deposits would be the Belgian Congo. Einstein knew the Belgian royal family, and his signature was important in warning them as well as being a source of credibility to the US President, Franklin D Roosevelt.

History continues to be a small place. Einstein had worked with Szilárd previously; They’d invented a refrigerator together in 1926.

The letter, dictated by Einstein in German, then translated by Szilard to a stenographer — who thought he was a nutcase, talking about extremely powerful bombs, and moreso when he signed off in Einstein’s name — follows;

Dear Mr Roosevelt

Some recent work by E. Fermi and L. Szilard, which has been communicated to me in manuscript, leads me to expect that the element uranium may be turned into a new and important source of energy in the immediate future. Certain aspects of the situation which has arisen seem to call for watchfulness and, if necessary, quick action on the part of the Administration. I believe therefore that it is my duty to bring to your attention the following facts and recommendations:

In the course of the last four months it has been made probable—through the work of Joliot in France as well as Fermi and Szilard in America—that it may become possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium-like elements would be generated. Now it appears almost certain that this could be achieved in the immediate future.

This phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable—though much less certain—that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed. A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory. However, such bombs might very well prove to be too heavy for transportation by air.

The United States has only very poor ores of uranium in moderate quantities. There is some good ore in Canada and the former Czechoslovakia, while the most important source of uranium is Belgian Congo.

In view of this situation you may think it desirable to have some permanent contact maintained between the Administration and the group of physicists working on chain reactions in America. One possible way of achieving this might be for you to entrust with this task a person who has your confidence and who could perhaps serve in an inofficial capacity. His task might comprise the following:

a) to approach Government Departments, keep them informed of the further development, and put forward recommendations for Government action, giving particular attention to the problem of securing a supply of uranium ore for the United States.

b) to speed up the experimental work, which is at present being carried on within the limits of the budgets of University laboratories, by providing funds, if such funds be required, through his contacts with private persons who are willing to make contributions for this cause, and perhaps also by obtaining the co-operation of industrial laboratories which have the necessary equipment.

I understand that Germany has actually stopped the sale of uranium from the Czechoslovakian mines which she has taken over. That she should have taken such early action might perhaps be understood on the ground that the son of the German Under-Secretary of State, von Weizsäcker, is attached to the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut in Berlin where some of the American work on uranium is now being repeated.

Yours very truly,

Albert Einstein

It’s a pretty good letter, and it highlights how prescient these people were. Sort of.

You see, this letter directly led to the creation of the Manhattan project. In 1947 he was quoted saying; “had I known that the Germans would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb, I would have done nothing”. Einstein wrote the letter to prevent the Nazis having one… not to end with the US gaining one.

But Roosevelt was convinced, a committee was formed, and the modern equivalent of $100,000 was cleared in graphite and uranium ore.

In this letter is an important note though; by this time, Germany had started looking into its own atomic program, and had ceased all exports of uranium, as Einstein told Szilárd. It was an arms race.

F.D.R was given a budget to approve before congress. Two billion dollars, or seventy billion in 2016 dollars — twice the budget of the entire Marine corps.

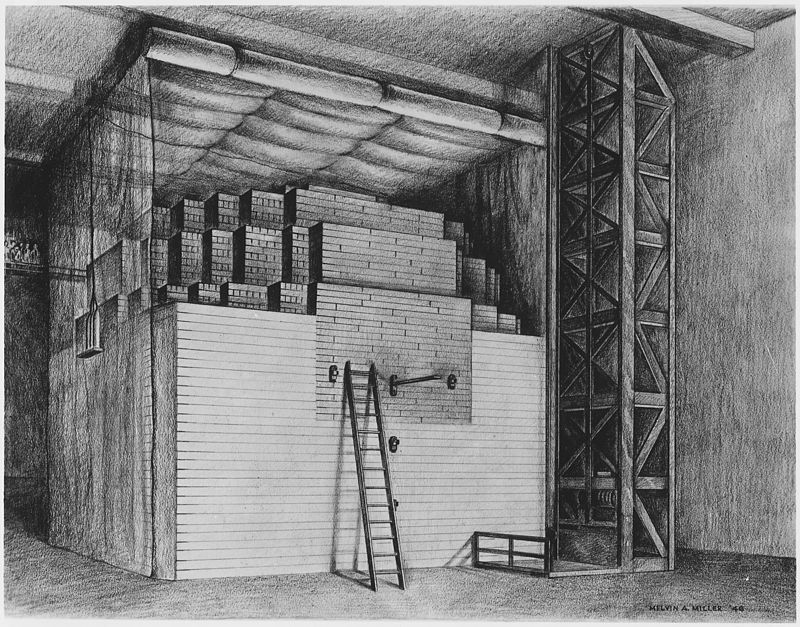

So now we get to Stagg Field. In it was the famous Chicago Pile 1, the world’s first self-sustaining nuclear reactor. “A crude pile of black bricks and wooden timbers”, according to Fermi.

Fermi himself had only been able to get two tons of uranium metal. Not enough for the stack to go critical. The Westinghouse Lamp Company was brought in to make up the extra three tons needed.

The lightbulb manufacturers made apparatus out of metal bins nicked from local markets, put important things in the basement and the ceiling when they ran out of space, all in an effort to supply the war effort with uranium for… some reason. An alloy of sorts, they were told.

Yeah, a lot of the uranium for the first ever nuclear reactor, like 60% of it, was literally refined in a dustbin at some point.

Everyone did the math time and time again. The Chicago pile would go critical — that was, a self-sustaining reaction that would enrich the uranium, and produce plutonium — without going supercritical — which is what a nuclear bomb is.

Men with axes to cut apart the timbers stood at the sides, the suicide squad. Another held a rod up by a rope. If the radiation got excessive he’d keel over and die, dropping a cadmium rod that would absorb neutrons… ideally saving the city. Another, Samuel Allison, stood ready with a bucket of concentrated cadmium nitride, which he was to throw over the pile, if the radiation didn’t kill him first.

All the math checked out, but this was still an untested hypothesis. They didn’t know this wouldn’t blow up the entire city of Chicago. There simply hadn’t been enough time or money to move everything safely out into the desert somewhere. It had no radiation shielding or cooling system.

But when the control rods were removed from the stack, the stack went critical.

The reaction worked.

FDR received a telegram: “The Italian Navigator—” Fermi, “— has landed safely in the new world.”

“How were the natives?”

“Very friendly.”

They celebrated with a bottle of chianti, which they drank with paper cups.

The Generals met with representatives of corporations like General Electric and explained what needed to be done. They were all read the espionage act; Information that left that room could be punishable by a minimum of thirty years, and up to death. If they wished to leave the room, they would be free to do so; Nobody wanted a parallel drawn between them and the Germans.

The men stayed.

By this time the Manhattan Project was also funneling resources into European agents to discover German labs, and found that they were making progress of their own.

Men like the Special Operations Executive were called upon — known by some of the few who knew of it at all as the Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare. They would discover the Axis heavy water facility in Norway — the sabotage of the Telemark atomic facilities is one of the cornerstone successes that prevented the Nazis achieving their own nuclear weapons.

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare was the creme de la creme of British special forces. Among its number was Christopher Lee — yes, that Christopher Lee — and its members were assigned to the Number 30 Assault Unit, which was overseen by Ian Fleming, who would later write the Bond novels based on his experiences. Also, they operated out of Bakers’ street, the famed house of Sherlock Holmes included.

So, James Bond and Saruman fought Nazis out of Sherlock Holme’s place in 1943. History’s a weird place.

There was an immense need to turn tons of uranium ore into refined plutonium. Dupont got the contract for Site W, the main plutonium refinement center. Dupont was offered a cost plus fixed-fee contract, but the President of the company didn’t want anything, even asked for the contract to explicitly exclude the company from acquiring any patent rights. For legal reasons a nominal fee of one dollar was agreed upon.

After the war, DuPont asked to be released from the contract early, and had to return 33 cents.

Site W was next to the Columbia river, whose water would be critical to cooling the reactors.

I cannot stress enough; It’s only been about three years since people even worked out that you could get nuclear chain reactions at all when Site W goes online, giving the world its first industrial scale plutonium reactor.

That would probably explain why it’s currently the biggest environmental disaster blight in the continental United States, and holds two thirds of all the liquid radioactive waste in the country.

Oak Ridge would house Site Y. In 1941, Oak Ridge had a population in the single digits. By 1943 it was the fifth largest city in Washington State, a town whose entire purpose was taking entire trainloads of pitchblend from Canada and turning it into tiny specks of metal dust.

Uranium was enriched — going from about 1% Uranium 235 to 99% Uranium 238, to about 5% 235 (reactor grade), to between 20-85% (weapon’s grade). After initial seperation, uranium was processed in the Y-12 facility, where electromagnetic coils refined it even further.

Unfortunately there wasn’t enough copper, due to wartime shortages, to make the coils. Instead, they took a loan from the treasury, of 12,300 tonnes of silver. However, when that amount was requested,the Under Secretary of the Treasury replied; “In the Treasury we do not speak of tons of silver; our unit is the troy ounce.”

The troy ounce, for the metric among you, is about 30 grams.

The loan was granted as 395 million troy ounces of silver.

Less than 0.036% out of more than $300 million worth of silver was lost to the process, the Treasury got back the rest. In exchange for the Treasury not charging interest on the loan, I presume the army didn’t charge for their security services.

The silver was made into calutrons, which is flipping mental. Okay so, how do you seperate Uranium 235 from 238? It’s chemically the same in every way. The only difference is the individual atoms of it are three neutrons of mass off. So a calutron – a California-designed cyclotron – accelerates the metal magnetically, then deflects it with other fields. The slight difference in mass causes the deflection to be slightly different.

The process was monitored on their readouts by highschool girls; pings and waves and other odd things that they didn’t understand. The young girls had no idea what they were actually doing, they were given simple instructions; If X happens, then do Y.

I should note here that the two sites produced materials for two different kinds of bomb. You see, the Manhattan project didn’t just invent the first atomic bomb, it invented the first two, simultaneously and in concert.

Fat Man was the same kind as the one used at the Trinity test site, an implosion-type bomb. Basically a 6 kilogram core of pure plutonium from the Dupont site, with another 4,000 kilos of conventional bomb wrapped around it. The shockwave meets in the middle, cracks the plutonium sphere into a polonium-beryllium core to dump a bunch of initial neutrons into it while it’s at double its usual density, and then watch as only 20% of it goes fissile, but that’s still enough to, say, level the entirety of Manhattan (which would kill 250,000 people outright).

Little Boy was a gun-type nuclear bomb. Meaning that instead of the fat, bulbous shape you’re familiar with it was a long piece of artillery tubing. There was a rod fired into a hole like an especially aggressive sexual euphemism, between them 50 kilograms of 85% enriched uranium. Remember what I said above about 5% being reactor-grade? Yeah.

See, you’ll also notice they only tested the implosion type bomb. Little Boy, the uranium gun-type, wasn’t tested before the big show. It was just dropped.

Because the scientists were absolutely confident the gun type would work. Fat Man was always plan-b, the unlikely one. A plutonium bomb, with an implosion mechanism? Problematic.

The gun-type enriched uranium, though… the harder part of that one was ensuring it didn’t work until the exact right moment. That one was scary.

Hell, they had to scrap the Thin Man project, which would have been a gun-type plutonium bomb, because they could not develop a firing mechanism fast enough. The plutonium would have reacted too soon, and gone off too incompletely, because by the time the fission reaction starts really kicking about, an artillery shell in a vacuum chamber might as well be frozen in place.

That’s how goddamn mental this project was.

Another fun fact of this era is Japanese balloon bombs.

Japan had a good strong air current between it and the US, so a common school project was to make balloon bombs, paper balloons holding about twenty kilograms explosives. Simple timers and gauges on them would drop the payload when, ideally, they were over the US.

It was imprecise guesswork. The Japanese launched 9,000 of them, expecting about 10% of that to ever make land. That’s… about right, actually. Good work, Japanese scientists.

Only about 300 were found.

And of those three hundred balloons that landed anywhere, anywhere in all of the US… I mean it, one of those things set fire to a garage in Detroit.

One actually hit Site Y at a pretty critical moment, pun intended.

The silk wires draped across the power lines leading from the dams, shorting out the cooling system for the plutonium reactor while it was in progress. Fortunately Dupont did its due dilligence, having made backups — the power was only out for a fifth of a second.

It’s one of my favourite war stories of just sheer unimaginable coincidence, though.

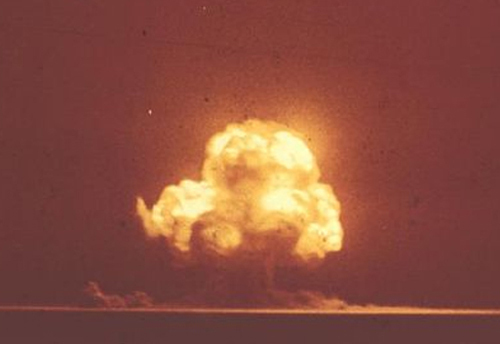

So they delivered the plutonium to the Trinity site where they made and armed the first atomic bomb, Gadget.

Men had been told that the scientists thought there was a small chance for the bomb to set off a chain reaction that would ignite the nitrogen and oxygen in the atmosphere, killing all life on Earth. As the bomb was primed they sat in the site chapel, crying.

Another physicist, a young Richard Feynman, sat in a jeep near the testing site, refusing the smoked glass lenses of his colleagues, who were also slathering on sunscreen as thickly as they could afford. He’d figured that all he really needed for safety was the polarized lens in the windscreen. As such, he’s the only man to have ever look directly at a nuclear blast and see it in full colour, and still have his sight.

I mean, it returned eventually.

The original testday had been postponed. The original zero hour was filled with storms. Rain filled the desert. It made photographs and filming the blast impossible from any distance that would make the cameras safe to recover, and everyone flinched every time lightning struck the steel dummy-bomb casing. It almost certainly wouldn’t have detonated the real one… But it would be an awful way to find out.

The bomb went off at 5:29am, July 26th. The desert lit up like God’s own flashbulb.

And we have pictures.

There were pressure gauges to get an accurate measure for the size of the blast, but the first, best guess comes from Fermi himself, watching the blast with a loose stack of notes.

You see, there’s this thing called a Fermi estimate, named for the scientist, where you just sort of… figure something out from best information available. Shorthand it.

So, to work out how many new cars are sold in the US each year, you sort of guess… well, maybe a third own cars, because that includes kids and people in cities and households with a shared car. Cool. Then you think, how many people bought a new car in the past five years? Most people buy used cars, so maybe a quarter or so bought new in that time. Which would make that about one in twenty bought a new car this year.

So 300,000,000 / 3 / 20 = 5,000,000. And the actual number, upon Googling, is about 6,000,000. Pretty close!

Fermi did that with Gadget, the bomb they dropped for the Trinity test. Dropped a stack of papers in his hand, watched them get caught in the shockwave, and made his guess based on that. Guessed the equivalent of 10 kilotons of TNT.

The actual blast was 20 kilotons, or as every physicist reading this thinks, ‘close enough’. It seriously is extremely close, and a testament to just how insanely brilliant Fermi was, and to his curiosity.

Roosevelt, the man who Einstein had written and had put his faith so completely into the hands of these scientists, did not live to see the Trinity test. He’d died just three months earlier, 12 of April 1945 — the month before Germany surrendered.

The plutonium fireball fused the desert sand into beautiful glass crystals with the immense heat and pressure, a substance now called “Trinitite”.

The new President Truman issued a statement to Japan, unconditional surrender of the Japanese armed forces — not the Emperor, notably — which will not result in the enslavement of the Japanese as a race or destroyed as a nation. And here one of the most famous lines ever penned to paper; “or face prompt and utter destruction.”

Chilling words. None outside the Manhattan project itself, at the time, knew what he meant.

Samuel J Walker identifies five key reasons for the use of the bombs on Japan, which I find interesting;

(1) the commitment to ending the war successfully at the earliest possible moment; (2) the need to justify the effort and expense of building the atomic bombs; (3) the hope of achieving diplomatic gains in the growing rivalry with the Soviet Union; (4) the lack of incentives not to use atomic weapons; and (5) hatred of the Japanese and a desire for vengeance.

It was sure to shorten the war by at least a year, and save thousands, if not millions, of lives overall. But it cannot be understated just how much a lot of people involved were itching to use the thing now that they’d made it.

Further… it almost wasn’t enough. It took two bombs to get the Japanese Emperor to sign the surrender, and even then his generals almost went into open revolt, planning assassination attempts to prolong the war further. Jesus Christ.

Most of the rest I’m sure you know. The bombs were loaded into specialized Silverplate bombers, designed to house and drop the gigantic bombs, and to fly the extended distance in one trip. There were three planes, with no fighter escorts. One was filled with recording equipment and civilian observers. The bomb was armed during the flight, so as not to risk exploding during takeoff.

The planes would have to fly hard, and fly fast, to outrun the shockwave, and the EMP that would frazzle their equipment.

Oh! A fun side note, another “History is so small” addendum; Zeppo Marx — as in, of the Marx Brothers, Groucho Marx’s brother, that one — designed and built the housing for Fat Man that would secure it in the plane and drop it, called a “Marman clamp”. He also invented the machine you see in hospitals that ‘flatlines’ when your heart stops. At the same time, Hedi Lamarr was making signal hopping technology for torpedoes that would end up being the mathematical basis for moder wi-fi and bluetooth, and the designs she’d made for Howard Hughes before the war had influenced the design of every, at the time, modern fighter jet.

Hollywood was weird in WW2.

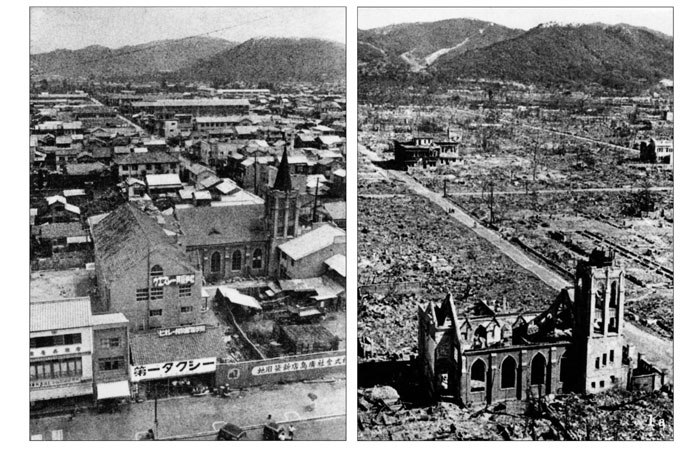

The Enola Gay took off on the 6th of August, 1945, carrying Little Boy. The weather was clear. Hiroshima lay in the center of flat plains. The 13 kiloton bomb dropped cleanly. 66,000 dead, 69,000 injured. What was left standing was a charred fireball, like the pits of Gehenna.

Bockscar, the plane carrying Fat Man, made three passes over its primary target, the city of Kokura. Fifty minutes it flew overhead, but the city was obscured by smoke from nearby Yahata, which had been firebombed to hell the day before. Fifty minutes Bockscar tried to make a clean line, but anti-aircraft fire was getting closer, and Japanese fighters were being alerted by radio.

They switched to their second target, Nagasaki.

There was a break in the cloud cover, but it wasn’t on-target, falling two miles off its intended target point. Even though the bomb was five kilotons stronger than Little Boy, it did less damage as a result, killing only 40,000 people outright.

With it, though, they had destroyed the manufacturing center that had produced the torpedoes that were used on Pearl Harbour.

What follows is a strange transition. You see, Steampunk is based on the optimism of the Industrial era before it gave way to the cynicism of the Modernism movement after WW1: The realization that all this technology had industrialized murder. The horrors of chemistry were plain to see for anyone who witnessed the Somme.

After the bombs dropped on Japan the world saw the true horrors modern science could wreak… and we see the rise of the Atompunk movement — the Jetsons, for instance — we had such hope that nobody could ever, would ever use it for evil ends or it would surely destroy us all.

As we went into the Cold War, science fiction became filled with hope and optimism again… because if we can make it through this, the concerns of this small and petty world, we now have the power to take to the stars. We have such a limitless, clean and brilliant energy source.

The belief that, with the unlocking of the power of the universe itself, all that came before would seem like the dark ages.

Humankind is pretty bizarre like that.

[1] Fun side note; The award for this was given by the The Secretary of State for Air, Winston Churchill. He’d been First Lord of the Admiralty during the first world war, and had pushed for modernization through the period, especially championing the importance of planes in modern combat. History can be a small place, sometimes.